Assessment |

Biopsychology |

Comparative |

Cognitive |

Developmental |

Language |

Individual differences |

Personality |

Philosophy |

Social |

Methods |

Statistics |

Clinical |

Educational |

Industrial |

Professional items |

World psychology |

Clinical: Approaches · Group therapy · Techniques · Types of problem · Areas of specialism · Taxonomies · Therapeutic issues · Modes of delivery · Model translation project · Personal experiences ·

Wilhelm Reich (March 24, 1897 – November 3, 1957) was an Austrian psychiatrist and psychoanalyst.[1]

Reich was a respected analyst for much of his life, focusing on character structure, rather than on individual neurotic symptoms.[2] He promoted adolescent sexuality, the availability of contraceptives and abortion, and the importance of economic independence to women's psychological health.[3]

He was also a controversial figure, particularly in later life, who came to be viewed by the psychoanalytic establishment as having "gone astray"[3] or succumbed to mental illness.[4]

Reich is best known for his studies on the link between human sexuality and emotions; the importance of what he called "orgastic potency"; and for what he said was the discovery of a form of energy that permeated the atmosphere and all living matter, which he called "orgone." He built boxes called "orgone accumulators," which patients could sit inside, and which were intended to harness the energy for what he believed were its health benefits. It was this work, in particular, that cemented the rift between Reich and the psychiatric establishment.[3][5][1]

Reich was living in Germany when Adolf Hitler came to power. Labeled a "communist Jew" by the Nazis,[6] he fled to Scandinavia before taking refuge in the United States in 1939.

In 1947, following a series of critical articles about orgone in The New Republic and Harper's, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) began an investigation into his claims, and, in 1954, won an injunction prohibiting the interstate sale of orgone accumulators. Two years later, Reich was charged with contempt of court for violating the injunction. He insisted on conducting his own defense, which included sending copies of all of his books to the judge. In June 1956, he was sentenced to two years in Federal prison; that August several tons of his publications were burned by agents of the FDA.[5][1] He died of heart failure in prison just over a year later, days before he was due to apply for parole.[7]

Early life

Reich was born in 1897 to Leon Reich, a prosperous farmer, and Cecilia Roniger, in Dobrzanica[8], a village near Peremyshliany, Galicia, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, now in Ukraine. Three years after his birth, the couple had a second son, Robert.

His father was by all accounts strict, cold, and jealous. He was Jewish, but Reich was later at pains to point out that his father had moved away from Judaism and had not raised his children as Jews; Reich wasn't allowed to play with Yiddish-speaking Jewish children, [9] and as an adult did not want to be described as Jewish. [10]

Shortly after his birth, the family moved south to a farm in Jujinetz, near Chernivtsi, Bukovina, where Reich's father took control of a cattle farm owned by his mother's family. Reich attributed his later interest in the study of sex and the biological basis of the emotions to his upbringing on the farm where, as he later put it, the "natural life functions" were never hidden from him. [11] Reich also spoke of sexual encounters he had had with a maid, where he witnessed intercourse between her and her boyfriend, and apparently later asked if he could "play" the part of the lover. He said that, by the time he was four years old, there were no secrets about sex for him. [9]

| “ | I had read somewhere that lovers get rid of any intruder, so with wild fantasies in my brain I slipped back to my bed, my joy of life shattered, torn apart in my inmost being for my whole life! — Wilhelm Reich. [12] | ” |

He was taught at home until he was 12, when his mother committed suicide by drinking a cheap household cleaner after being discovered having an affair with Reich's tutor, who lived with the family. In a report supposedly about a patient, Reich wrote about how deeply the affair had affected him, according to Myron Sharaf. Night after night, he had heard his mother creep to her lover's room, had followed her, and had overheard the couple's lovemaking. He felt ashamed, angry, and jealous; he wondered whether they would kill him if they realized he knew, and briefly had the thought of forcing his mother to have sex with him too, on pain of the father being told of the affair. He wrote that his "joy of life [was] shattered, torn apart from [his] inmost being for the rest of [his] life!" [12]

Torn between the desire to tell his father and the wish to protect his mother from his father's revenge, he later blamed himself for what happened, waking in the night overwhelmed by the idea that he had killed her. Her death was particularly brutal because of the method she chose, which left her in great pain for days before she died. The tutor was sent away, and Reich was left without his mother or his teacher, and with a powerful sense of guilt. [13]

He was sent to the all-male Czernowitz gymnasium, excelling at Latin, Greek, and the natural sciences. It appears to have been during this period that a skin condition developed that plagued Reich for the rest of his life. When it began is unclear, but it was diagnosed as psoriasis, and Sharaf speculates that it may have been triggered by his mother's suicide. Reich was given medication that contained arsenic, now known to make psoriasis worse.

Reich's father was "completely broken" by his wife's suicide. [14] In or around 1914, he took out a life insurance policy then stood for hours in a cold pond, apparently fishing, but in fact intending to commit slow suicide, according to Reich and his brother Robert. [15] He contracted pneumonia and then tuberculosis, and died in 1914 as a result of his illness; despite his insurance policy, no money was forthcoming. [15]

Reich managed the farm and continued with his studies, graduating in 1915 mit Stimmeneinhelligheit (unanimous approval). In the summer of 1915, the Russians invaded Bukovina and the Reich brothers fled to Vienna, losing everything. In his Passion of Youth, Reich wrote: "I never saw either my homeland or my possessions again. Of a well-to-do past, nothing was left."

Studies

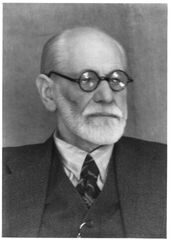

Sigmund Freud and Reich met in 1919 when Reich needed literature for a sexology seminar.

Reich joined the Austrian Army after school, serving from 1915-18, for the last two years as a lieutenant.

In 1918, when the war ended, he entered the medical school at the University of Vienna. As an undergraduate, he was drawn to the work of Sigmund Freud; the men first met in 1919 when Reich visited Freud to obtain literature for a seminar on sexology. Freud left a strong impression on Reich. Freud allowed him to start seeing analytic patients as early as late 1919 or early 1920. Reich was accepted as a guest member of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Association in the summer of 1920, and became a regular member in October 1920, at the age of 23. [16]

He was allowed to complete his six-year medical degree in four years because he was a war veteran, and received his M.D. in July 1922. [1]

His work

Early career

He worked in internal medicine at University Hospital, Vienna, and studied neuropsychiatry from 1922-24 at the Neurological and Psychiatric Clinic under Professor Wagner-Jauregg, who won the Nobel Prize in medicine in 1927.

In 1922, he set up private practice as a psychoanalyst, and became first clinical assistant, and later vice-director, at Freud's Psychoanalytic Polyclinic. He joined the faculty of the Psychoanalytic Institute in Vienna in 1924, and conducted research into the social causes of neurosis. It was at the Vienna Psychoanalytic Association that Reich met Annie Pink, a fellow analyst-in-training. They married, and had their first daughter, Eva, in 1924 and a second daughter in 1928. The couple separated in 1933, leaving the children with the mother.

Reich developed a theory that the ability to feel sexual love depended on a physical ability to make love with what he called "orgastic potency." He attempted to "measure" the male orgasm, noting that four distinct phases occurred physiologically: first, the psychosexual build-up or tension; second. the tumescence of the penis, with an accompanying "charge," which Reich measured electrically; third, an electrical discharge at the moment of orgasm, and fourth, the relaxation of the penis. He believed the force that he measured was a distinct type of energy present in all life forms and later called it "orgone." [6]

He was a prolific writer for psychoanalytic journals in Europe, and his book Character Analysis brought forth a small revolution [How to reference and link to summary or text] in the practice of psychoanalysis itself, and is still used today as a textbook for analytically oriented classes in medical schools. [How to reference and link to summary or text] Originally psychoanalysis was focused on the treatment of neurotic symptoms. Character Analysis was a major step in the development of what today would be called ego psychology. In Reich's view a person's entire character (or personality), not only individual symptoms, could be looked at and treated as a neurotic phenomenon. The book also introduced Reich's theory of "body armoring." He argued that unreleased psychosexual energy could produce actual physical blocks within muscles and organs, and that these act as a "body armor," preventing the release of the energy. An orgasm was one way to break through the armor. These ideas developed into a general theory of the importance of a healthy sex life to overall well-being, a theory compatible with Freud's views.

Reich agreed with Freud that sexual development was the origin of mental disorder. They both believed that most psychological states were dictated by unconscious processes; that infant sexuality develops early but is repressed, and that this has important consequences for mental health. At that time a Marxist, Reich argued that the source of sexual repression was bourgeois morality and the socio-economic structures that produced it. As sexual repression was the cause of the neuroses, the best cure would be to have an active, guilt-free sex life. He argued that such a liberation could come about only through a morality not imposed by a repressive economic structure. [17] In 1928, he joined the Austrian Communist Party and founded the Socialist Association for Sexual Counselling and Research, which organized counselling centers for workers—in contrast to Freud, who was perceived as treating only the bourgeoisie.

Reich employed an unusual therapeutic method. He used touch to accompany the talking cure, taking an active role in sessions, feeling his patients' chests to check their breathing, repositioning their bodies, and sometimes requiring them to remove their clothes, so that men were treated wearing shorts and women in bra and panties. These methods caused a split between Reich and the rest of the psychoanalytic community. [6]

In 1930, he moved his practice to Berlin and joined the Communist Party of Germany. His best-known book, The Sexual Revolution, was published at this time in Vienna. Advocating free contraceptives and abortion on demand, he again set up clinics in working-class areas and taught sex education, but became too outspoken even for the communists, and eventually, after his book The Mass Psychology of Fascism was published, he was expelled from the party in 1933.

In this book Reich categorized fascism as a symptom of sexual repression. The book was banned by the Nazis when they came to power. He realized he was in danger and hurriedly left Germany disguised as a tourist on a ski trip to Austria. Reich was expelled from the International Psychological Association in 1934 for political militancy. He spent some years in Denmark, Sweden, and Norway, before leaving for the United States in 1939.

The bion experiments

From 1934-37, based for most of the period in Oslo, Reich conducted experiments seeking the origins of life. He examined protozoa, which are single-celled creatures with nuclei. He grew cultured vesicles using grass, beach sand, iron, and animal tissue, boiling them, adding potassium and gelatin. Having heated the materials to incandescence with a heat-torch, he noted bright, glowing, blue vesicles, which, he claimed, could be cultured, and which gave off an observable radiant energy, which he called orgone. He named the vesicles "bions" and believed they were a rudimentary form of life, or halfway between life and non-life. When he poured the cooled mixture onto growth media, bacteria were born. Based on various control experiments Reich dismissed the idea that the bacteria were already present in the air, or in the other materials used. Reich's The Bion Experiments on the Origin of Life was published in Oslo in 1938, leading to attacks in the press that he was a "Jew pornographer" who was daring to meddle with the origins of life. [6]

T-bacilli

In 1936, in Beyond Psychology, Reich wrote that "[s]ince everything is antithetically arranged, there must be two different types of single-celled organisms: (a) life-destroying organisms or organisms that form through organic decay, (b) life-promoting organisms that form from inorganic material that comes to life."

This idea of spontaneous generation led him to believe he had found the cause of cancer. He called the life-destroying organisms "T-bacilli," with the T standing for Tod, German for death. He described in The Cancer Biopathy how he had found them in a culture of rotting cancerous tissue obtained from a local hospital. He wrote that T-bacilli were formed from the disintegration of protein; they were 0.2 to 0.5 micrometre in length, shaped like lancets, and when injected into mice, they caused inflammation and cancer. He concluded that, when orgone energy diminishes in cells through ageing or injury, the cells undergo "bionous degeneration" or death. At some point, the deadly T-bacilli start to form in the cells. Death from cancer, he believed, was caused by an overwhelming growth of the T-bacilli.

Orgone accumulators and cloudbusters

Reich built "orgone accumulators" to harness orgone, which he believed was responsible for emotions and sexuality. Wild rumors spread that his "sex boxes" caused uncontrollable erections.

He designed a "cloudbuster," which he said could manipulate streams of orgone energy to produce rain.

In March 1938, Hitler annexed Austria. Reich's ex-wife and daughters had already left for the U.S., and in August 1939, Reich sailed out of Norway on the last boat to leave before the war began. He settled in Forest Hills, Long Island, and in 1946, married Ilse Ollendorf, with whom he had a son, Peter.

It was during this period, according to some researchers, that Reich appeared to suffer a breakdown. They say that he became paranoid and revised parts of his earlier works to remove references to Marxist theory. [1] Reich's defenders say that Reich's revisions were minor, confined only to the English-speaking American period of his work, and were primarily sexological, clinical, or scientific in nature. Reich was one of the first of the European socialists to break ranks completely with the Communist Party; for example, in his book Mass Psychology of Fascism, which he wrote after a trip to Russia, he identified communism as "Red Fascism". His defenders say that the charge of paranoia is intended to discredit Reich's critique of Marxism. American writer Jim Martin alleges that many of those who have attacked Reich's biophysical research—on the orgone accumulator, for example—are themselves leftist and Marxist. [18]

In 1940, Reich built boxes called orgone accumulators to concentrate atmospheric orgone energy; some were for lab animals, and some were large enough for a human being to sit inside. Reich said orgone was the "primordial cosmic energy", blue in color, which he claimed was omnipresent and responsible for such things as weather, the color of the sky, gravity, the formation of galaxies, and the biological expressions of emotion and sexuality. Composed of alternating layers of ferrous metals and insulators with a high dielectric constant, his orgone accumulators had the appearance of a large, hollow capacitor. He believed that sitting inside the box might provide a treatment for cancer and other illnesses. It was the construction of these boxes that caught the attention of the press, leading to wild rumors that they were "sex boxes" which caused uncontrollable erections. [6]

Reich also designed a "cloudbuster" with which he said he could manipulate streams of orgone energy in the atmosphere to induce rain by forcing clouds to form and disperse. Based on experiments with the orgone accumulator, he argued that orgone energy was a negatively-entropic force in nature which was responsible for concentrating and organizing matter. During one drought-relief expedition to Arizona, he claimed to have observed UFOs, as well as at Orgonon, Maine, and speculated that orgone might be used for the propulsion of UFOs. Because Reich and his co-workers claimed to have seen clouds appear with the UFOs, they called it DOR (Deadly Orgone). [How to reference and link to summary or text]

According to Reich's theory, illness was primarily caused by depletion or blockages of the orgone energy within the body. He conducted clinical tests of the orgone accumulator on people suffering from a variety of illnesses. The patient would sit within the accumulator and absorb the "concentrated orgone energy". He built smaller, more portable accumulator-blankets of the same layered construction for application to parts of the body. The effects observed were claimed to boost the immune system, even to the point of destroying certain types of tumors, though Reich was hesitant to claim this constituted a "cure." The orgone accumulator was also tested on mice with cancer, and on plant-growth, the results convincing Reich that the benefits of orgone therapy could not be attributed to a placebo effect. He had, he believed, developed a grand unified theory of physical and mental health. [19]

Orgone experiment with Einstein

Reich discussed orgone accumulators with Albert Einstein in 1941.

On December 30, 1940, Reich wrote to Albert Einstein saying he had a scientific discovery he wanted to discuss, and on January 13, 1941 went to visit Einstein in Princeton. They talked for five hours, [20] and Einstein agreed to test an orgone accumulator, which Reich had constructed out of a Faraday cage made of galvanized steel and insulated by wood and paper on the outside. Einstein agreed that if, as Reich suggested, an object's temperature could be raised without an apparent heating source, it would be "a bomb" in physics. [21] This heating effect would be an amazing result since it would allow the construction of a perpetual motion machine, [22] which would violate the laws of thermodynamics.[23]

Reich supplied Einstein with a small accumulator during their second meeting, and Einstein performed the experiment in his basement, which involved taking the temperature atop, inside, and near the device. He also stripped the device down to its Faraday cage to compare temperatures. Over the course of a week, in both cases, Einstein observed a rise in temperature, and confirmed Reich's finding. [24] Reich concluded that the heat was the result of a novel form of energy—orgone energy—that had accumulated inside the Faraday cage. However, one of Einstein's colleagues at Princeton interpreted the phenomenon as resulting from thermal convection currents. Einstein concurred that the experiment could be explained by convection. [24]

Reich responded with a 25-page letter to Einstein, expressing concern that "convection from the ceiling" would join "air germs" and "Brownian movement" to explain away new findings, according to Reich's biographer, Myron Sharaf. Sharaf writes that Einstein conducted some more experiments, but then regarded the matter as "completely solved." [24]

The correspondence between Reich and Einstein was published by Reich's press as The Einstein Affair in 1953, possibly without Einstein's permission. [25]

Controversy

The Brady article and the FDA

Reich was investigated by the FBI when he arrived in the U.S. because he was an immigrant with a communist background. The FBI released 789 pages of its files on Reich in 2000; a State Department press release stated:

This German immigrant described himself as the Associate Professor of Medical Psychology, Director of the Orgone Institute, President and research physician of the Wilhelm Reich Foundation and discoverer of biological or life energy. A 1940 security investigation was begun to determine the extent of Reich's communist commitments. A board of Alien Enemy Hearing judged that Dr. Reich was not a threat to the security of the U.S. In 1947, a security investigation concluded that neither the Orgone Project nor any of its staff were engaged in subversive activities or were in violation of any statute within the jurisdiction of the FBI. [26]

Myron Sharaf writes that Reich's life in America was relatively peaceful until 1947. There were a few of what Sharaf calls snide articles, and rumors about Reich's sanity, but no organized opposition. Then on May 26, 1947, an article appeared in The New Republic entitled "The Strange Case of Wilhelm Reich" by freelance writer Mildred Edie Brady. The subhead was "The man who blames both neuroses and cancer on unsatisfactory sexual activities has been repudiated by only one scientific journal." [27]

Sharaf writes that the article consisted of combined truths, half-truths, and lies. Brady wrote:

Orgone, named after the sexual orgasm, is, according to Reich, a cosmic energy. It is, in fact, the cosmic energy. Reich has not only discovered it; he has seen it, demonstrated it and named a town — Orgonon, Maine — after it. Here he builds accumulators of it which are rented out to patients, who presumably derive 'orgastic potency' from it. [27]

Sharaf writes that the implication was clear: the accumulators gave orgastic potency, the lack of which causes cancer. Therefore, the claim for the accumulators was that they cured cancer. Brady argued that the "growing Reich cult" had to be dealt with. [28]

Two months later, on July 23, Dr. J.J. Durrett, director of the Medical Advisory Division of the Federal Trade Commission, wrote to the FDA asking them to look into Reich's claims about the health benefits of orgone. [29] The FDA assigned an investigator named Wood to the case, who learned that Reich had built 250 accumulators; the FDA concluded that they were dealing with a "fraud of the first magnitude." [30] Sharaf writes that the FDA suspected a "sexual racket" of some kind; questions were asked about the women associated with orgonomy and "what was done with them." [31]

| “ | I would like to plead for my right to investigate natural phenomena without having guns pointed at me. I also ask for the right to be wrong without being hanged for it. — Wilhelm Reich. [32] | ” |

In November, Reich wrote in Conspiracy. An Emotional Chain Reaction: "I would like to plead for my right to investigate natural phenomena without having guns pointed at me. I also ask for the right to be wrong without being hanged for it ... I am angry because smearing can do anything and truth can do so little to prevail, as it seems at the moment." [33] Sharaf writes that Reich came to believe that Mildred Brady was a Stalinist acting under orders from the Communist Party, a "communist sniper," as Reich called her. [34][35]

On February 10, 1954, the U.S. Attorney for Maine, acting on behalf of the FDA, filed a complaint seeking a permanent injunction under Sections 301 and 302 of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, to prevent interstate shipment of orgone-therapy equipment and literature. [2] Reich refused to appear in court, apparently believing that no court was in a position to evaluate his work. In his cover letter for the response he submitted to the court, he wrote to Judge Clifford:

My factual position in the case as well as in the world of science of today does not permit me to enter the case against the Food and Drug Administration, since such action would, in my mind, imply admission of the authority of this special branch of the government to pass judgment on primordial, pre-atomic cosmic orgone energy.

I, therefore, rest the case in full confidence in your hands.[36]

Because of Reich's failure to appear, Judge Clifford granted the injunction on March 19, 1954. [3] His ruling ordered that all written materials that mentioned "orgone energy" — including papers and pamphlets, and ten of Reich's books — were to be destroyed. It further stated that additional copies of his books, including revised classics like The Mass Psychology of Fascism, could not be published unless all references to "orgone energy" were deleted.

Imprisonment and death

In May 1956, Reich was arrested for technical violation of the injunction when an associate moved some orgone-therapy equipment across a state line, and Reich was charged with contempt of court. Once again, he refused to arrange a legal defense. He was brought in chains to the courthouse in Portland, Maine. Representing himself, he admitted to having violated the injunction and arranged for the judge to be sent copies of his books. He was sentenced to two years' imprisonment.

Dr. Morton Herskowitz, a fellow psychiatrist and friend of Reich's wrote of the trial: "Because he viewed himself as a historical figure, he was making a historical point, and to make that point he had conducted the trial that way. If I had been in his shoes, I would have wanted to escape jail, I would have wanted to be free, etc. I would have conducted the trial on a strictly legal basis because the lawyers had said, 'We can win this case for you. Their case is so weak, so when you let us do our thing we can get you off.' But he wouldn't do it." [4]

On June 5, 1956, FDA officials traveled to Orgonon, Reich's 200-acre (80-hectare) estate near Rangeley, Maine, where they destroyed the accumulators, and on June 26, burned many of his books. On August 25, 1956 and again on March 17, 1960, [5] the remaining six tons of his books, journals and papers were burned in the 25th Street public incinerator in New York's lower east side (Gansevoort incinerator). In March 1957, he was sent to Danbury Federal Prison, where a psychiatrist examined him, recording: "Paranoia manifested by delusions of grandiosity and persecution and ideas of reference." [6]

Reich died in his sleep of heart failure on November 3, 1957 in the federal penitentiary in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, shortly before he was due to apply for parole. Not one psychiatric or established scientific journal carried an obituary. Time Magazine noted on November 18, 1957:

Died. Wilhelm Reich, 60, once-famed psychoanalyst, associate, and follower of Sigmund Freud, founder of the Wilhelm Reich Foundation, lately better known for unorthodox sex and energy theories; of a heart attack in Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary, Pa; where he was serving a two-year term for distributing his invention, the "orgone energy accumulator" (in violation of the Food and Drug Act), a telephone-booth-size device which supposedly gathered energy from the atmosphere, and could cure, while the patient sat inside, common colds, cancer and impotence. [5]

Reich was buried in Orgonon. At his own instruction, his granite headstone, adorned with a metal rendering of his face, reads simply:

The burial site looks out over an unobscured view of Rangeley Lake. Next to the grave stands a replica of Reich's invention, the "cloudbuster". The Wilhelm Reich Museum now sits at the top of Orgonon, in the building which housed Reich's laboratory, teaching, and psychiatric treatment facilities.

Status of his work

New research journals devoted to Reich's work began to appear in the 1960s. Physicians and natural scientists with an interest in Reich organized small study groups and institutes, and new research efforts were undertaken. James DeMeo undertook research at the University of Kansas into Reich's atmospheric theories. [37] A later study by DeMeo subjected Reich's sex-economic theory to cross-cultural evaluations. [38], later included in DeMeo's opus magnum Saharasia. [39]

Reich's orgone research has not found an open reception; the mainstream scientific community remains largely uninterested in, and at times hostile to, to his ideas. There is some use of orgone accumulator therapy by psychotherapists in Europe, particularly in Germany. [How to reference and link to summary or text] A double-blind, controlled study of the psychological and physical effects of the orgone accumulator was carried out by Stefan Müschenich and Rainer Gebauer at the University of Marburg and appeared to validate some of Reich's claims. [40] The study was later reproduced by Günter Hebenstreit at the University of Vienna. [41] William Steig, Norman Mailer, William S. Burroughs, Jerome D. Salinger and Orson Bean have all undergone Reich's orgone therapy.

Reich's influence is felt in modern psychotherapy. He was a pioneer of body psychotherapy and several emotions-based psychotherapies, influencing Fritz Perls' Gestalt therapy and Arthur Janov's primal therapy. See also Neo-Reichian massage. His pupil Alexander Lowen, the founder of bioenergetic analysis, Charles Kelley, the founder of Radix therapy, and James DeMeo ensure that his research receives widespread attention. Many practising psychoanalysts give credence to his theory of character, as outlined in his book Character Analysis (1933, enlarged 1949). The American College of Orgonomy, [42] founded by the late Elsworth Baker M.D., and the Institute for Orgonomic Science, [43] led by Dr. Morton Herskowitz, still use Reich's original therapeutic methods.

Nearly all Reich's publications have been reprinted, apart from his research journals which are available as photocopies from the Wilhelm Reich Museum. The first editions are not available: Reich continuously amended his books throughout his life, and the owners of Reich's intellectual property actively forbid anything other than the latest revised versions to be reprinted. In the late 1960s, Farrar, Straus & Giroux republished Reich's major works. Reich's earlier books, particularly The Mass Psychology of Fascism, are regarded as historically valuable. [44]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Biography, The Wilhelm Reich Museum, retrieved August 14, 2006.

- ↑ "Wilhelm Reich," Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Sharaf, Myron. Fury on Earth: A Biography of Wilhelm Reich. Da Capo Press, 1994, p. 4.

- ↑ Sharaf, Myron. Fury on Earth: A Biography of Wilhelm Reich. Da Capo Press, 1994, p. 8.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Obituary notice for Wilhelm Reich, Time Magazine, November 18, 1957.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Cantwell, Alan. "Dr. Wilhelm Reich: Scientific Genuis or Medical Madman?", New Dawn, Issue no. 84, May–June 2004, retrieved August 14, 2006.

- ↑ Sharaf, Myron. Fury on Earth: A Biography of Wilhelm Reich. Da Capo Press, 1994, p. 477.

- ↑ Presently it is spelled Dobryanichi (also Dobrjanici), in Ukrainian: Добряничі. See location at Google Maps.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Sharaf, Myron. Fury on Earth: A Biography of Wilhelm Reich. Da Capo Press, 1994, p. 39.

- ↑ Sharaf, Myron. Fury on Earth: A Biography of Wilhelm Reich. Da Capo Press, 1994, p. 463.

- ↑ Reich, Wilhelm. "Background and scientific development of Wilhelm Reich," Orgone Energy Bulletin V, 1953, p. 6, cited in Sharaf 1994, p. 40 and p. 488, footnote 10.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Reich, Wilhelm. "Ueber einen Fall von Durchbruch der Inzestschranke in der Pubertät," Zeitschrift für Sexualwissenschaft, VII, 1920, 222-223, cited in and translated by Sharaf 1994, p. 43 and p. 448, footnote 12.

- ↑ Sharaf, Myron. Fury on Earth: A Biography of Wilhelm Reich. Da Capo Press, 1994, p. 42-46.

- ↑ Reich, Wilhelm. "Ueber einen Fall von Durchbruch der Inzestschranke in der Pubertät," op cit, cited in Sharaf 1994, p. 47 and p. 489, footnote 21.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Sharaf, Myron. Fury on Earth: A Biography of Wilhelm Reich. Da Capo Press, 1994, p. 48.

- ↑ Sharaf, Myron. Fury on Earth: A Biography of Wilhelm Reich. Da Capo Press, 1994, p. 58.

- ↑ D'Aloia, Alessandro. "Marxism and Psychoanalysis: Notes on Wilhelm Reich’s Life and Works", Marxist.com, retrieved August 14, 2006.

- ↑ Martin, Jim. Wilhelm Reich and the Cold War, Flatland Books, Mendocino, CA, 2000.

- ↑ Klee, Gerald D. "What ever happened to orgone therapy?", The Maryland Psychiatric Society, Summer 2001; Vol. 28, No. 1; Pg 13-15, retrieved August 14, 2006.

- ↑ Sharaf, Myron. Fury on Earth: A Biography of Wilhelm Reich. De Capo Press, 1994, p. 285.

- ↑ Brian, Denis. 1996. Einstein: A Life, John Wiley & Sons, New York, p.326.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) About New Energy Science and Technology", New Energy Foundation, Inc., 2003, retrieved August 14, 2006.

- ↑ Perpetual Motion Machines at The British Columbia Institute of Technology

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Sharaf, Myron. Fury on Earth: A Biography of Wilhelm Reich. De Capo Press, 1994, p. 286.

- ↑ Sharaf, Myron. Fury on Earth: A Biography of Wilhelm Reich. De Capo Press, 1994, p. 288.

- ↑ "FBI adds new subjects to electronic reading room", U.S. State Department, March 2, 2000.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Brady, Mildred. "The Strange case of Wilhelm Reich," The New Republic, May 26, 1947 cited in Sharaf, Myron. Fury on Earth: A Biography of Wilhelm Reich. Da Capo Press, 1994, p. 360.

- ↑ Sharaf, Myron. Fury on Earth: A Biography of Wilhelm Reich. Da Capo Press, 1994, p. 361.

- ↑ FDA file on Reich, cited in Sharaf, Myron. Fury on Earth: A Biography of Wilhelm Reich. Da Capo Press, 1994, p. 363 and footnote 6, p. 513.

- ↑ FDA file on Reich, cited in Sharaf, Myron. Fury on Earth: A Biography of Wilhelm Reich. Da Capo Press, 1994, p. 364 and footnote 11, p. 513.

- ↑ Greenfield, Jerome. Wilhelm Reich Vs. the U.S.A.. W.W. Norton, 1974, p. 69, cited in Sharaf, Myron. Fury on Earth: A Biography of Wilhelm Reich. Da Capo Press, 1994, p. 364 and footnote 13, p. 513.

- ↑ Reich, Wilhelm. Conspiracy. An Emotional Chain Reaction, item 386A, cited in Sharaf, Myron. Fury on Earth: A Biography of Wilhelm Reich. Da Capo Press, 1994, p. 367 and footnote 14, p. 513.

- ↑ Reich, Wilhelm. Conspiracy. An Emotional Chain Reaction, item 386A, cited in Sharaf, Myron. Fury on Earth: A Biography of Wilhelm Reich. Da Capo Press, 1994, p. 367 and footnote 14, p. 513.

- ↑ Sharaf, Myron. Fury on Earth: A Biography of Wilhelm Reich. Da Capo Press, 1994, p. 367.

- ↑ Jim Martin writes that Michael Straight, a former member of the Cambridge Apostles and friend of some of those involved in the Soviet-Cambridge spy ring, was the publisher of the Brady articles, and that the attack on Reich may have been prompted by Reich's turning his back on Marxism. (Martin, Jim. Wilhelm Reich and the Cold War, Flatland Books, Mendocino, CA, 2000.)

- ↑ "Wilhelm Reich's Response to FDA's Complaint for Injunction", February 25, 1954, posted on orgone.org.

- ↑ DeMeo, James. "Preliminary Analysis of Changes in Kansas Weather Coincidental to Experimental Operations with a Reich Cloudbuster," KU Geography-Meteorology Dept, Thesis, 1979.

- ↑ DeMeo, James. "On the Origins and Diffusion of Patrism: The Saharasian Connection," KU Geography-Meteorology Dept, Dissertation, 1986

- ↑ DeMeo, James: "Saharasia: The 4000 BCE Origins of Child Abuse, Sex-Repression, Warfare and Social Violence in the Deserts of the Old World. The Revolutionary Discovery of a Geographic Basis to Human Behavior". Greensprings OR, 1986

- ↑ Müschenich, Stefan & Gebauer, Rainer: Der Reich'sche Orgonakkumulator. Naturwissenschaftliche Diskussion, praktische Anwendung, experimentelle Untersuchung. Frankfurt/Main: Nexus-Verlag 1987

- ↑ Hebenstreit, Günter: Der Orgonakkumulator nach Wilhelm Reich. Eine experimentelle Untersuchung zur Spannungs-Ladungs-Formel. Univ. Wien, Dipl.-Arbeit, 1995

- ↑ The American College of Orgonomy

- ↑ Institute for Orgonomic Science

- ↑ A good overview of Reich's work is Wilhelm Reich: The evolution of his work by David Boadella. A bibliography on orgonomy gives full citations to university dissertations, and to controlled experiments replicating Reich's work on bions, the orgone accumulator, and the cloudbuster.

Reich's writings

- German-language books

- Der triebhafte Charakter : Eine psychoanalytische Studie zur Pathologie des Ich, 1925

- Die Funktion des Orgasmus : Zur Psychopathologie und zur Soziologie des Geschlechtslebens, 1927

- Dialektischer Materialismus und Psychoanalyse, 1929

- Geschlechtsreife, Enthaltsamkeit, Ehemoral : Eine Kritik der bürgerlichen Sexualreform, 1930

- Der Einbruch der Sexualmoral : Zur Geschichte der sexuellen Ökonomie, 1932

- Charakteranalyse : Technik und Grundlagen für studierende und praktizierende Analytiker, 1933

- Massenpsychologie des Faschismus, 1933 (original Marxist edition, banned by the Nazis and the Communists)

- Was ist Klassenbewußtsein? : Über die Neuformierung der Arbeiterbewegung, 1934

- Psychischer Kontakt und vegetative Strömung, 1935

- Die Sexualität im Kulturkampf : Zur sozialistischen Umstrukturierung des Menschen, 1936

- Die Bione : Zur Entstehung des vegetativen Lebens, 1938

- English-language books

- American Odyssey:Letters and Journals 1940-1947

- Beyond Psychology:Letters and Journals 1934-1939

- The Bioelectrical Investigation of Sexuality and Anxiety

- The Bion Experiments: On the Origins of Life

- Function of the Orgasm (Discovery of the Orgone, Vol.1)

- The Cancer Biopathy (Discovery of the Orgone, Vol.2)

- Character Analysis

- Children of the Future: On the Prevention of Sexual Pathology

- Contact With Space: Oranur Second Report

- Cosmic Superimposition: Man's Orgonotic Roots in Nature (1951)

- Early Writings

- Ether, God and Devil (1949)

- Genitality in the Theory and Therapy of Neuroses (actually the original version of Function of the Orgasm from 1927)

- The Invasion of Compulsory Sex-Morality

- Listen, Little Man!

- Mass Psychology of Fascism

- The Murder of Christ (Emotional Plague of Mankind, Vol.2)

- The Oranur Experiment

- The Orgone Energy Accumulator, Its Scientific and Medical Use

- Passion of Youth: An Autobiography, 1897-1922

- People in Trouble: Emotional Plague of Mankind, Vol.1)

- Record of a Friendship: The Correspondence of Wilhelm Reich and A.S. Neill (1936-1957)

- Reich Speaks of Freud

- Selected Writings: An Introduction to Orgonomy

- The Sexual Revolution

- The Einstein Affair, 1953

Further reading

- Baker, Elsworth F. Man In The Trap, Macmillan, NY, 1967.

- Bean, Orson. Me And The Orgone, St. Martin's Press, NY, 1971.

- Boadella, David. Wilhelm Reich, The Evolution Of His Work, Henry Regnery, Chicago, 1973.

- Boadella, David. (Ed.): In The Wake Of Reich, Coventure, London, 1976.

- Brady, Mildred Edie. "The Strange Case of Wilhelm Reich," New Republic, May 26, 1947

- ___________________. "The New Cult of Sex and Anarchy," Harper's, April 1947.

- Cantwell, Alan. "Dr. Wilhelm Reich: Scientific Genius or Medical Madman New Dawn Magazine, May-June 2004

- Corrington, Robert S. Wilhelm Reich: Psychoanalyst and Radical Naturalist, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, NY, 2003

- DeMeo, James. The Orgone Accumulator Handbook: Construction Plans, Experimental Use and Protection Against Toxic Energy, Natural Energy Works, Ashland, Oregon 1989.

- DeMeo, James. (Ed.) "On Wilhelm Reich And Orgonomy" (Pulse of the Planet #4), Natural Energy Works, Ashland, Oregon 1993.

- DeMeo, James. "Saharasia: The 4000 BCE Origins of Child-Abuse, Sex-Repression, Warfare and Social Violence, In the Deserts of the Old World", Natural Energy Works, Ashland, Oregon 1998.

- DeMeo, James & Senf, Bernd. (Eds.) Nach Reich: Neue Forschungen zur Orgonomie: Sexualokonomie, Die Entdeckung Der Orgonenergie (After Reich: New Research in Orgonomy: Sex-Economy, Discovery of the Orgone Energy), Zweitausendeins Verlag, Frankfurt, 1998.

- DeMeo, James. (Ed.) "Heretic's Notebook: Emotions, Protocells, Ether-Drift and Cosmic Life Energy, With New Research Supporting Wilhelm Reich", Natural Energy Works, Ashland, Oregon 2002.

- Greenfield, Jerome. Wilhelm Reich Vs. The USA, W.W. Norton, NY, 1974.

- Guillon, Claude. Pour en finir avec Reich, Alternative diffusion, 1978.

- Herskowitz, Morton. Emotional Armoring: An Introduction to Psychiatric Orgone Therapy, Transactions Press, NY 1998.

- Kendrick, William. "The Analyst as Outsider", a review of Myron Sharaf's Fury on Earth: A Biography of Wilhelm Reich, The New York Times, April 3, 1983.

- Laska, Bernd A.: Sigmund Freud contra Wilhelm Reich Auszug aus Laska, Bernd A. Wilhelm Reich. Bildmonographie. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1981, 1999

- Mann, Edward: Orgone. Reich And Eros: Wilhelm Reich's Theory Of The Life Energy, Simon & Schuster, NY, 1973.

- Mann, Edward & Hoffman, Ed. The Man Who Dreamed Of Tomorrow: A Conceptual Biography Of Wilhelm Reich, J.P. Tarcher, 1980.

- Martin, Jim. Wilhelm Reich and the Cold War, Flatland Books, Mendocino, CA, 2000.

- Meyerowitz, Jacob. Before the Beginning of Time, rRp Publishers, Easton, PA 1994.

- Norris, Lance. "Cloudhopping", Dutchco International, 2007

- Ollendorff, Ilse. Wilhelm Reich: A Personal Biography, St. Martin's Press, NY, 1969.

- Raknes, Ola. Wilhelm Reich And Orgonomy, St. Martin's Press, NY, 1970; Penguin, Baltimore, 1970.

- Reich, Peter. A Book Of Dreams, Harper & Row, NY, 1973.

- Ritter, Paul, Ed. Wilhelm Reich Memorial Volume, Ritter Press, Nottingham, England, 1958.

- Senf, Bernd. Die Wiederentdeckung des Lebendigen (The Rediscovery of the Living), Zweitausendeins Verlag, Frankfurt, 1996.

- Wilson, Robert Anton. Wilhelm Reich in Hell, Aires Press, 1998.

- Wyckoff, James. Wilhelm Reich: Life Force Explorer, Fawcett, Greenwich, CT, 1973.

- Los Orgones, Argentinian site of Orgonomy

- Bibliography on Orgonomy, a full listing of scholarly works on Wilhelm Reich

- Orgonon - The Wilhelm Reich Museum

- Aetherometry - The Science of Massfree Energy; encompasses experimental and theoretical crystallization of, and enlargement upon, Reich's work

- Orgone Biophysical Research Laboratory

- On-Line Bibliography on Orgonomy (Includes list of University Theses and Dissertations focused on Reich's work)

- PORE, Public Orgonomic Research Exchange (Includes a Biography (Timeline) of Wilhelm Reich and his Orgonomic Research)

- Reich's FBI File

- Skeptic's Dictionary: orgone energy, Wilhelm Reich

- Response to Martin Gardner's Attack on Reich and Orgone Research in the Skeptical Inquirer

- The American College of Orgonomy

- Scientific Reproduction of Reich's Biophysical Experiments

- A Skeptical Scrutiny of the Works and Theories of Wilhelm Reich

- Wilhelm Reich within the Project LSR ("orgone forgone")

- Listen, Little Man - Wilhelm Reich

- Marxism and Psychoanalysis: Notes on Wilhelm Reich's life and work

- The Einstein Affair, Orgone Institute Press, 1953

- Reference to Reich-Einstein correspondence in Oregon State University archives

- 2 chapters of Gone Dark by "W.B. Smyth", supposed "document" of the Philadelphia experiment. "50 Years after Albert Einstein: The Failure of the Unified Field", the beginning talks of Reich.

- A description of the experiment with Einstein

- A "rain engineering" service offered by a Singaporean company based on Reich's work.

- Looking at the work of Reich, Naessens, Bechamp, Rife and Enderlein with regard to disease research

- The Einstein experiments

- Aspden, H (2001) "Gravity and its thermal anomaly: was the Reich-Einstein experiment evidence of energy inflow from the aether?", Infinite Energy, 41:61.

- Bearden, T (2002) "Energy from the vacuum", Cheniere Press, Santa Barbara, CA, pp. 333-337.

- Brian, Denis. Einstein: A Life, John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1996. ISBN 0-471-11459-6 Reich is discussed on pages 325-327, 382, 399.

- Clark, Ronald W. Einstein: The Life and Times, New York: Avon, 1971, ISBN 0-380-01159-X Reich is on pages 689-90 of the paperback edition.

- Correa, P & Correa, A (1998, 2001) "The thermal anomaly in ORACs and the Reich-Einstein experiment: implications for blackbody theory", Akronos Publishing, Concord, ON, Canada, ABRI monograph AS2-05.

- Correa PN & Correa AN (2001) "The reproducible thermal anomaly of the Reich-Einstein experiment under limit conditions", Infinite Energy, 37:12.

- Mallove, E (2001) "Breaking Through: A Bombshell in Science", Infinite Energy, 37:6.

- Mallove, E (2001) "Breaking Through: Aether Science and Technology", Infinite Energy, 39:6.

See also

- Sex economy (essay)

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia (view authors). |