No edit summary |

m (Reverting apparent test edit.) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{ClinPsy}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | |||

| ⚫ | |||

Dr. '''Thomas Stephen Szasz''' (born April 15, [[1920]] in Budapest, Hungary) is Professor Emeritus in [[Psychiatry]] at the [[State University of New York]] Health Science Center in Syracuse, New York. Szasz is a critic of the moral and scientific foundations of psychiatry. |

Dr. '''Thomas Stephen Szasz''' (born April 15, [[1920]] in Budapest, Hungary) is Professor Emeritus in [[Psychiatry]] at the [[State University of New York]] Health Science Center in Syracuse, New York. Szasz is a critic of the moral and scientific foundations of psychiatry. |

||

| Line 7: | Line 9: | ||

His views on involuntary treatment follow from [[classical liberalism|classical liberal]] roots which are based on the principles that each person has the right to bodily and mental self-ownership and the right to be free from violence from others. Szasz is a principled [[libertarian]] who believes that the practice of [[medicine]], use and sale of drugs, and sexual relations, should be private, contractual, and outside of state jurisdiction. |

His views on involuntary treatment follow from [[classical liberalism|classical liberal]] roots which are based on the principles that each person has the right to bodily and mental self-ownership and the right to be free from violence from others. Szasz is a principled [[libertarian]] who believes that the practice of [[medicine]], use and sale of drugs, and sexual relations, should be private, contractual, and outside of state jurisdiction. |

||

| − | == Headline text == |

||

| − | kjklnklnkléá |

||

Together with the [[Church of Scientology]], Szasz co-founded the [[Citizens Commission on Human Rights]] (CCHR) in 1969 to fight what it sees as human rights crimes committed by psychiatrists and other mental health professionals. |

Together with the [[Church of Scientology]], Szasz co-founded the [[Citizens Commission on Human Rights]] (CCHR) in 1969 to fight what it sees as human rights crimes committed by psychiatrists and other mental health professionals. |

||

Revision as of 16:42, 13 February 2007

Assessment |

Biopsychology |

Comparative |

Cognitive |

Developmental |

Language |

Individual differences |

Personality |

Philosophy |

Social |

Methods |

Statistics |

Clinical |

Educational |

Industrial |

Professional items |

World psychology |

Clinical: Approaches · Group therapy · Techniques · Types of problem · Areas of specialism · Taxonomies · Therapeutic issues · Modes of delivery · Model translation project · Personal experiences ·

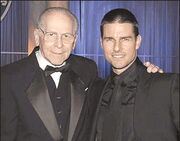

Photograph by Jeffrey A. Schaler.

Dr. Thomas Stephen Szasz (born April 15, 1920 in Budapest, Hungary) is Professor Emeritus in Psychiatry at the State University of New York Health Science Center in Syracuse, New York. Szasz is a critic of the moral and scientific foundations of psychiatry.

He is well known for his books The Myth of Mental Illness and The Manufacture of Madness: A Comparative Study of the Inquisition and the Mental Health Movement which set out some of the arguments with which he is most associated.

His views on involuntary treatment follow from classical liberal roots which are based on the principles that each person has the right to bodily and mental self-ownership and the right to be free from violence from others. Szasz is a principled libertarian who believes that the practice of medicine, use and sale of drugs, and sexual relations, should be private, contractual, and outside of state jurisdiction.

Together with the Church of Scientology, Szasz co-founded the Citizens Commission on Human Rights (CCHR) in 1969 to fight what it sees as human rights crimes committed by psychiatrists and other mental health professionals.

Szasz's main arguments

Dr. Thomas Szasz with actor Tom Cruise at a CCHR annual dinner.

Szasz's main arguments can be summarised as follows:

- The myth of mental illness: Schizophrenia and other mental disorders are medical metaphors. While people behave and think in ways that are very disturbing, this does not mean they have a disease. To Szasz, people with mental illness have a "fake disease." Schizophrenia is "The Sacred Symbol of Psychiatry" according to another Szasz book. To be a true disease, the entity must somehow be capable of being approached, measured, or tested in scientific fashion." According to Szasz, disease must be found on the autopsy table and meet pathological definition instead of being voted into existence by members of the American Psychiatric Association. Mental illnesses are "like a" disease, argues Szasz, putting mental illness in a semantic metaphorical language arts category. Psychiatry is a pseudo-science that parodies medicine by using medical sounding words invented over the last 100 years. To be clear, heart break and heart attack belong to two completely different categories. Psychiatrists are but "soul doctors" who deal with the spiritual "problems in living" that have troubled people forever. Psychiatry, through various Mental Health Acts has become the secular state religion according to Thomas Szasz. Psychiatry is a social control system, not a medical science according to Dr. Szasz.

- Separation of psychiatry and the state: If we accept that 'mental illness' is a euphemism for behaviours that are disapproved of, then the state has no right to force psychiatric 'treatment' on these individuals. Similarly, the state should not be able to interfere in mental health practices between consenting adults (for example, by legally controlling the supply of psychotropic drugs or psychiatric medication). The medicalization of government produces a "therapeutic state," which in an extreme case led to the Nazi genocide against Jews, Gypsies, homosexuals, and other "undesirables."

- Presumption of competence: Just as legal systems work on the presumption that a person is innocent until proven guilty, individuals accused of crimes should not be presumed incompetent simply because a doctor or psychiatrist labels them as such. Mental incompetence should be assessed like any other form of incompetence, i.e., by purely legal and judicial means with the right of representation and appeal by the accused.

- Death Control: In an analogy to birth control, Szasz argues that individuals should be able to choose when to die without interference from medicine or the state, just as they are able to choose when to conceive without outside interference. He considers suicide to be among the most fundamental rights, but he opposes state-sanctioned euthanasia.

- Abolition of the insanity defense: Szasz believes that testimony about the mental competence of a defendant should not be admissible in trials. Psychiatrist testifying about the mental state of an accused person's mind have about as much business as a priest testifying about the religious state of a person's soul in our courts. Insanity was a legal tactic invented to circumvent the punishments of the Church, which, at the time included confiscation of the property of those who committed suicide, which often left widows and orphans destitute. Only an insane person would do such a thing to his widow and children, it was successfully argued. Legal mercy masquerading as medicine, said Szasz.

- Abolition of involuntary mental hospitalization: No one should be deprived of liberty unless he is found guilty of a criminal offense. Depriving a person of liberty for what is said to be his own good is immoral. Just as a person suffering from terminal cancer may refuse treatment, so should a person be able to refuse psychiatric treatment.

- Our Right to Drugs: The case for a free-market. Although Szasz is skeptical about the merits of psychotropic medications, he favors the repeal of drug prohibition. "Because we have a free market in food, we can buy all the bacon, eggs, and ice cream we want and can afford. If we had a free market in drugs, we could similarly buy all the barbiturates, chloral hydrate, and morphine we want and could afford."

Szasz is associated with the anti-psychiatry movement of the 1960s and 1970s. He has attempted to distance himself from the connection, though, noting that he is not opposed to the practice of psychiatry if it is non-coercive. He maintains that psychiatry should be a contractual service between consenting adults with no state involvement. He favors the abolition of involuntary hospitalization for mental illness. According to Szasz, involuntary mental hospitalization is a crime against humanity which, if unopposed, will expand into "pharmacratic" dictatorship.

Criticism

Szasz taught at SUNY and conducted a small non drug using, rather than traditional psychiatric practice for individuals with "problems in living"; there is nothing in his writings to suggest that he treats patients whom mainstream psychiatrists would describe as having a serious mental illness. Szasz's critics maintain that, contrary to Szasz's views, such illnesses are now regularly "approached, measured, or tested in scientific fashion." [1] The list of groups that reject his opinion that mental illness is a myth include the American Psychiatric Association (APA), the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), the President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD), the National Mental Health Association (NMHA), and the Treatment Advocacy Center (TAC). Dr. Szasz is noted for answering his critics.

Analysis of criticism

The journalist Jacob Sullum, who received a 2004 Thomas S. Szasz Award,[2] summarized some specific criticisms of Szasz's views when he noted that critics "offer various alternatives to the Szaszian perspective, which insists upon an objectively measurable bodily defect as the sine qua non of a true disease.

Among other things, Sullum points out, critics argue that some so-called mental illnesses are genuine brain diseases, although their precise etiologies have not been figured out yet. If mental illness is a myth, they note, so is physical illness, because both categories have fuzzy boundaries and are to a large extent culturally determined. Viewing mental illness as a myth, they assert, is a fiction that is necessary to maintain the integrity of psychotherapy as a moral enterprise. Critics, Sullum notes, also contend that the distinction between mental and physical disease is misleading, since (as the American Psychiatric Association puts it) 'there is much that is "physical" in mental disorders and much 'mental' in "physical" disorders."[3]

==Publications

For comprehensive list see this Szasz bibliography

Books

- Szasz, T.S. (1957f). Pain and Pleasure: A Study of Bodily Feelings. New York: Basic Books.

- Szasz, T.S. (1961f). The Myth of Mental Illness: Foundations of a Theory of Personal Conduct. New York: Paul B. Hoeber.

- Szasz, T.S. (1965f). Psychiatric Justice. New York: Macmillian.

- Szasz, T.S. (1970d). Ideology and Insanity: Essays on the Psychiatric Dehumanization of Man. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

- Szasz, T.S. (1970f). The Manufacture of Madness: A Comparative Study of the Inquisition and the Mental Health Movement. New York: Harper Row

External links

- The Thomas S. Szasz Cybercenter for Liberty and Responsibility

- The Szasz Blog

- the Thomas Szasz Discussion Group

- The Case Against Psychiatric Coercion, by Thomas S. Szasz

- Mental Disorders are not Diseases, by Thomas S. Szasz

- Interview: Curing the Therapeutic State

- Thomas Szasz Quotes

- Psychiatric News article on Thomas Szasz

- Thomas Szasz's OISM Honorary Membership Website

- Thomas Szasz's Manifesto

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia (view authors). |