| (16 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{CompPsy}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | The Social Intelligence Hypothesis is that (1) [[social intelligence]], that is, complex [[socialization]] such as [[politics]], [[romance]], [[family relationships]], [[arguments]], [[collaboration]], [[reciprocity]], and [[altruism]], was the driving force in developing the size of human brains and (2) today provides our ability to use those large brains in complex social circumstances.<ref name="lse">Professor [[Nicholas Humphrey]], London School of Economics - http://www.lse.ac.uk</ref> That is, it was the demands of living together that drove our need for intelligence generally. |

||

| ⚫ | <span style="font-size:13px;line-height:21px;">[[Nick Humphreys]], in "</span>''The Social Function of Intellect" ''<span style="font-size:13px;line-height:21px;">(1976)</span>'', ''<span style="font-size:13px;line-height:21px;">first proposed that the adaptive value of intelligent behaviour in animals lies not just in technical domains such as tool use for extractive foraging (the so-called "''ecological intelligence hypothesis"''), but through group living a </span>''variety ''<span style="font-size:13px;line-height:21px;">of different selective pressures would lead to the evolution of more "intelligent" behavior.<ref></span>[http://www.humphrey.org.uk/papers/1976SocialFunction.pdf Humphrey, N. (1976) The Social Function of intellect. In Growing Points in ethology (eds P.P.G. Bateson & R.A> Hinde), pp.303-317. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press]<span style="font-size:13px;line-height:21px;"> .</span><span style="font-size:13px;line-height:21px;"></ref> The social intelligence hypothesis thus encompasses the''''' '''''</span>'''''[[Machiavellian intelligence|Machiavellian intelligence hypothesis]] '''''<span style="font-size:13px;line-height:21px;">and </span>'''''social brain hypothesis '''''<span style="font-size:13px;line-height:21px;">which can be seen as related theories as to how social living would lead to greater intelligence. </span> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | *''Exploiting, |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | *''Exploiting, deceiving ''and ''out-manoeuvring ''conspecifics will be adaptive and require being able to understand both the ''consequences of their own behavior ''and to calculate the ''behavior of others, ''as well as a variety of other complex abilities. The latter ability is now called "theory of mind" and has been studied intesively in the comparative perspective. The '''''[[Machiavellian intelligence|Machiavellian intelligence hypothesis]] '''''specifically refers to the evolution of social intelligence in this domain. |

||

*''Co-operation ''between conspecifics, what Humphreys termed ''sympathy'', may evolve in conjuction with more selfish forms of behavior as outlined in the machiavellian intelligence hypothesis. Humphreys believed that relationships based on<span style="font-size:13px;"> "mutual give and take", will also be adaptive for individuals. </span> |

*''Co-operation ''between conspecifics, what Humphreys termed ''sympathy'', may evolve in conjuction with more selfish forms of behavior as outlined in the machiavellian intelligence hypothesis. Humphreys believed that relationships based on<span style="font-size:13px;"> "mutual give and take", will also be adaptive for individuals. </span> |

||

The research program of social intelligence has mostly explored in comparative cognition research, comparing the cogntiive abilities of different animals. Much less work has been done on providing concrete evidence that adaptations for social living (i.e. social learning) are actually adaptive.<ref>e.g. [http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/anthro/faculty/silk/PDF%20Files%20Pubs/Silk%202007%20Value%20of%20Sociality.pdf Silk, J. (2007) The Adaptive value of sociality in mammalian groups. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 362, 539-559.] </ref> |

The research program of social intelligence has mostly explored in comparative cognition research, comparing the cogntiive abilities of different animals. Much less work has been done on providing concrete evidence that adaptations for social living (i.e. social learning) are actually adaptive.<ref>e.g. [http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/anthro/faculty/silk/PDF%20Files%20Pubs/Silk%202007%20Value%20of%20Sociality.pdf Silk, J. (2007) The Adaptive value of sociality in mammalian groups. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 362, 539-559.] </ref> |

||

| + | =="The Social Brain": Brain Evolution and Group Size== |

||

| − | {{contents}} |

||

| + | ===The Relationship between neocortex size and group size in primates=== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | [[File:The_social_brain_hypothesis_pic.jpg|thumb|left|Comparing relative neocortex size, to various social and ecological factors. One should note that the power to detect an effect is very small here (n=29) and that the neocortex ratio is plotted logarithmically with a base of ten.]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | |||

| − | ==Social learning and its adaptive value== |

||

| + | One way in which the social intelligence hypothesis has been investigated is through comparative research on how [[group size]] and [[brain size]] co-evolve. Even though brain size has been increasing over time in most species<ref>Schultz, S. & Dunbar, R.I.M. (2006)[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1560022/pdf/rspb20053283.pdf Both social and ecological factors predict ungulate brain size. Proceedings of the Royal Society, 273, 207-215.] </ref>, researchers have tried to show that variation in brain size within animal orders can be predicted by group size. <span style="font-size:13px;line-height:21px;">It is assumed that the overall group size is a good index of social complexity and the extent to which primates may have a fitness advantage in enhancing their "social cognition" (through any of the mechanisms outlined in the introduction). Primate brain evolution was first investigated, however the line of research has also been extended to other groups with mixed results.</span> |

||

| + | |||

| + | [[Robin Dunbar]] famously posited "The Social Brain Hypothesis" (1998) summasing evidence for the comparative increase in brain size and social group size in simians. He showed that neither overall brain size, cerebrum size or neocortex size predicted group size, but the ratio of the neocortex against the rest of the brain is a very good predictor (r = .63; even when 8 other variables are controlled for).<ref>Dunbar, R.I.M. (1998) The Social Brain Hypothesis. ''Evolutionary Anthropology, ''178-190.</ref> He also included various measures ecological complexity (percentage of fruit in diet, extractive foraging and home range) to test if ''ecological ''explanations can also select for greater brain size. In his original analyses (Dunbar 1992, 1998) none did, but in later analyses with a greater sample size (and statistical power) a relatively smaller effect was shown for ecological variables (see below). However, Dunbar's analysis was mostly post hoc in that many reserachers did not know what was the best way to measure brain size, and 3 different methods are used by Dunbar for the neocortex alone (and only one was a significant predictor of intelligence). "[[Dunbars number]]" refers to the predicted group size of humans when looking only at their neocortex size, which is '''150'''. |

||

| + | |||

| + | <span style="font-size:13px;line-height:21px;">Dunbar has tended to argue that</span>'' social complexity''<span style="font-size:13px;line-height:21px;"> (in terms of hierarchies and quantity) as well as </span>[[machiavellian intelligence]]<span style="font-size:13px;line-height:21px;"> (deception and coalition formation) as being important drivers of this effect, however, others have argued that</span>'' social learning''<span style="font-size:13px;line-height:21px;"> of efficient foraging strategies has been the principle selection driver. </span><ref>Reader, S. M. & Laland, K. N. (2002) Social intelligence, innovation, and enhanced brain size in primates.'' Proceedings of the National Academy of Science''. 99, 4436–4441.</ref><ref>Dunbar, R.I.M. (2007) Understandign primate brain evolution. ''Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, ''362, 649-658.</ref><span style="font-size:13px;line-height:21px;"> It is neither not very clear whether researchers like Dunbar are arguing that a form of domain-free </span>''general intelligence''<span style="font-size:13px;line-height:21px;"> evovles or a specialised form of </span>''social cognitive intelligence''<span style="font-size:13px;line-height:21px;"> when looking at neocortex evolution.</span> |

||

| + | |||

| + | ===The social brain hypothesis in non-primates=== |

||

| + | These findings have been extended to other taxa. <span style="font-size:13px;line-height:21px;">In ungalates, the neocortex ratio correlated with level of sociality and the type of social system (soltary, monogamous, harem, large stable group), however the small sample size (n=38) for neocortex data meant that statistical techniques used to correct shared phylogeny (more related animals being more similar and having correlated features) could only be used for total brain size.<ref>Schultz, S. & Dunbar, R.I.M (2006) Both social and ecologial factors predict ungalate brain size. </span>''Proceedings of the Royal Society B, ''<span style="font-size:13px;line-height:21px;">273, 207-215.</span><span style="font-size:13px;line-height:21px;"></ref> Total brain size (relative to body size) also correlates with habitat and social system, but </span>'''not group size'', '''''<span style="font-size:13px;line-height:21px;">sociality or diet. Group size did not correlate with neocortex size in any of the analyses, suggesting that in ungalates other factors are a better index of social complexity. </span><span style="font-size:13px;line-height:21px;">In odontocete species, relative total brain size also correlates with pod (group) size. <ref>Marino, L. (1996) What can Dolpins tell us about primate evolution? ''Evolutionary Anthropology, ''81-87.</ref></span> |

||

| + | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | One should note that the social intelligence hypothesis is not ecology free. Many researchers juxtapose ecological vs social evolutionary driving forces of intelligence, but the social intelligence hypothesis posists that access to environmental resources can be maximised through the evolution of intelligent behavior.<ref>Dunbar, R.I.M, Shultz, S. (2007) Understanding primate brain evolution. ''Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, ''362, 649-658.</ref> |

||

| + | |||

| + | Either way, one may expect that areas other than the neocortex may be important for other forms of evolution of intelligent behaviour in ecological contexsts (i.e. remembering the location of fruit trees), and indeed the hippocampus size has been found to vary with ranging area.<ref>Barton, R.A. & Purvis, A. (1994) PRimate brains and ecology: Looking beneath the surface. In Anderson, J.R., Thierry, B. & Herrenschmidt, N. (eds). ''Current Primatology, ''pp. 1-12. Strasbourg: University of Stresbourg Press.</ref> We would expect the hippocampus, which is involved in memory, rather than neocortex size to evolve with some of these ecological factors. When using a larger sample of primate species than the origina reports (e.g. Dunbar 1998), Robin Dunbar found that ecological factors do correlate with brain size measures, however things like diet (percentage of fruit) and habitat are weaker predictors than social factors. In addition, diet only significantly to contributes to overall brain size (r = .19, ''p ''= .01) and cerebrum (''r = ''.16, ''p '= .''16) measures, and not the neocortex, which suggests that it plays a role as ''a '''metabolic constraint on brain growth'''.'''''<ref><span style="font-size:13px;line-height:21px;">Dunbar, R.I.M. (2007) Understandign primate brain evolution. </span>''Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, ''<span style="font-size:13px;line-height:21px;">362, 649-658.</span><span style="font-size:13px;line-height:21px;"></ref> '''This is because brain tissue is costly, and species which can reduce the percentage of this energetically costly and fragile tissue will need to gather less food.'''<ref>Aiello, L.C. & Wheeler, P. (1995) The Expensive-Tissue Hypothesis: The Brain and the Digestive System in Human and Primate Evolution. ''Current Anthropology, ''36, 2, 199-221.</ref>''' |

||

| + | ==<span style="font-size:17.77777862548828px;">Why does living in (larger) social groups lead to evolution in intelligent behavior?</span>== |

||

| + | ===<span style="font-size:16px;line-height:21px;">Deception, coalition-formation and social cognition amongst primates, the drivers of brain evolution?</span>=== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | |||

| + | The machiavellian intelligence hypothesis posits that individuals abilties to ''exploit, decieve ''and ''out-maneuver ''others will lead to a competetive advantage to gaining resources within a group. Some researchers have gone as far to label social the social lives of primates as "poltical" in the sense to which power, hierarchy and social maneuvering plays a key role in access to resources such as females. <ref>de Waal, F. (1998) ''Chimpanzee Politics: Power and Sex among Apes''. John Hopkins University Press.</ref> However, very little research has associated these behaviors with reproductive fitness, which is needed to show that sociality leads to selective pressure on intelligence. Some evidence exists, however, which is described below. |

||

| + | |||

| + | <span style="font-size:13px;line-height:21px;">Dominance rank effects reproducitve performance in many taxa<ref>Pusey, A. & Packer, C. (1994) The Ecology of relationships. IN: ''Behavioural ecology ''(eds J. Krebs & N.B. Davies), pp. 254-283. 4th ed. Oxford: Blackwell.</ref>, however in primate species with larger neocortices, male </span><span style="font-size:13px;line-height:21px;">social rank does not predict mating success as well, presumably because the larger neocortex of individuals allows lower ranking primates too use social methods such as deception to gain mates.</span><span style="font-size:13px;line-height:21px;"> </span><ref>Pawlowski, B., Lowen, C. B. & Dunbar, R. I. M. (1998) Neocortex size, social skills and mating success in primates. <span style="font-size:13px;line-height:21px;">''Behaviour'', 135, 357–368</span><span style="font-size:13px;line-height:21px;"></ref><span style="font-size:13px;line-height:21px;"> </span><span style="font-size:13px;line-height:21px;">In addition, reported deception rate in the primatology literature very strongly (r = 0.74) predicts neocortex ratio, when the reported rate of deception is controlled for the "research effort" on a particular species.</span><span style="font-size:13px;line-height:21px;"> </span><ref>Byrne, R.W. & Corp, N. (2004) Neocortex size predicts deception rate in primates. ''Proceedings of the Royal Society London B, ''271, 1693-1699.</ref> |

||

| + | |||

| + | Some have criticised the evidence that primates decieve others as purely "anecdotal" and as being anthromorphic projects on behavior. Others have said that the evidence that primates form coalitions habitually is lacking. <ref>Barret, L. ''et al. ''(2007) Social brains, simple minds: does social complexity really require cognitive complexity? ''Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, ''362, 561-575.</ref> |

||

| + | |||

| + | ===<span style="font-size:16px;line-height:21px;">Social learning and i</span><span style="font-size:16px;line-height:21px;">ts adaptive value</span>=== |

||

[[Animal Cognition|Social learning is a widespread skill amongst animals]], however it varies in complexity across taxa, although research many speces other than primates is still in its infancy. There are varying views on its adaptive value, however, with the prevailing assumption that it is an adaptive skill being questioned by some. <ref>Rieucau, G. & Giraldeau, L. (2011) Exploring the costs and benefits of social infomation use: an appraisal of current experimental evidence. ''Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, ''366, 1567, 949-957.</ref> |

[[Animal Cognition|Social learning is a widespread skill amongst animals]], however it varies in complexity across taxa, although research many speces other than primates is still in its infancy. There are varying views on its adaptive value, however, with the prevailing assumption that it is an adaptive skill being questioned by some. <ref>Rieucau, G. & Giraldeau, L. (2011) Exploring the costs and benefits of social infomation use: an appraisal of current experimental evidence. ''Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, ''366, 1567, 949-957.</ref> |

||

| + | ===The social intelligence hypothesis and hominin evolution=== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | Professor of early history at Reading University, Steve Mithen, believes that there are two key periods of human brain growth that contextualize the social intelligence hypothesis. The first was around two million years ago, when the brain more than doubled, from around 450cc to 1,000cc by 1.8 million years ago. Brain tissue is very expensive metabolically, so it must have served an important purpose. Mithen believes that this growth was because people were living in larger, more complex groups, and had to keep track of more people and relationships, which required a greater mental capacity and so a larger brain.<ref name="shes">Steven Mithen Professor in Archaeology, School of Archaeology, Geography and Environmental Science, University of Reading - http://www.reading.ac.uk/archaeology/about/staff/s-j-mithen.aspx</ref> |

||

| + | The second growth in human brain size occurred between 600,000 and 200,000 years ago, when the brain reached its modern size. This growth is still not fully explained. Mithen’s believes that it is related to the evolution of language. Language is probably the most complex cognitive task we undertake. It is directly related to social intelligence because we mainly use language to mediate our social relationships.<ref name="shes" /> |

||

| + | |||

| + | So social intelligence was a critical factor in brain growth, social and cognitive complexity co-evolve.<ref>Benoit Hardy-Vallée, ''The Philosophy of Social Cognition''. 2008</ref> |

||

| + | ==Differences from intelligence== |

||

| + | Professor Nicholas Humphrey points to a difference between intelligence and social intelligence. Some autistic children are extremely intelligent because they are very good at observing and memorising information, but they have low social intelligence. Similarly, chimpanzees are very adept at observation and and memorisation, sometimes better than humans, but may be regarded as less skilled in managing social and interpersonal relationships. What they lack is a theory of other people's minds. For a long time, the field was dominated by [[behaviorism]], that is, the theory that one could understand animals including humans just by observing their behavior and finding correlations. But recent theories indicate that one must consider the inner structure behaviour.<ref name="lse" /> |

||

| + | |||

| + | Both [[Nicholas Humphrey]] and [[Ross Honeywill]] believe that it is [[social intelligence]], or the richness of our qualitative life, rather than our quantitative intelligence, that makes humans what they are; for example what it is like to be a human being living at the centre of the conscious present, surrounded by smells and tastes and feels and the sense of being an extraordinary metaphysical entity with properties which hardly seem to belong to the physical world. This is social intelligence. |

||

| + | |||

| + | ==See also== |

||

| + | *[[Social skills]] |

||

| + | |||

| ⚫ | |||

<references/> |

<references/> |

||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {{enWP|Social intelligence}} |

||

| + | [[Category:Intelligence]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Social skills]] |

||

Latest revision as of 12:50, 20 September 2013

Assessment |

Biopsychology |

Comparative |

Cognitive |

Developmental |

Language |

Individual differences |

Personality |

Philosophy |

Social |

Methods |

Statistics |

Clinical |

Educational |

Industrial |

Professional items |

World psychology |

Animals · Animal ethology · Comparative psychology · Animal models · Outline · Index

The Social Intelligence Hypothesis is that (1) social intelligence, that is, complex socialization such as politics, romance, family relationships, arguments, collaboration, reciprocity, and altruism, was the driving force in developing the size of human brains and (2) today provides our ability to use those large brains in complex social circumstances.[1] That is, it was the demands of living together that drove our need for intelligence generally.

Nick Humphreys, in "The Social Function of Intellect" (1976), first proposed that the adaptive value of intelligent behaviour in animals lies not just in technical domains such as tool use for extractive foraging (the so-called "ecological intelligence hypothesis"), but through group living a variety of different selective pressures would lead to the evolution of more "intelligent" behavior.[2] The social intelligence hypothesis thus encompasses the Machiavellian intelligence hypothesis and social brain hypothesis which can be seen as related theories as to how social living would lead to greater intelligence.

Humphreys posited a variety of different consequences of group living, such as:

- Social learning allows for intelligent behavior to spread without the need for individuals innovating, and can actually "substitute" intelligence in some ways.

- Exploiting, deceiving and out-manoeuvring conspecifics will be adaptive and require being able to understand both the consequences of their own behavior and to calculate the behavior of others, as well as a variety of other complex abilities. The latter ability is now called "theory of mind" and has been studied intesively in the comparative perspective. The Machiavellian intelligence hypothesis specifically refers to the evolution of social intelligence in this domain.

- Co-operation between conspecifics, what Humphreys termed sympathy, may evolve in conjuction with more selfish forms of behavior as outlined in the machiavellian intelligence hypothesis. Humphreys believed that relationships based on "mutual give and take", will also be adaptive for individuals.

The research program of social intelligence has mostly explored in comparative cognition research, comparing the cogntiive abilities of different animals. Much less work has been done on providing concrete evidence that adaptations for social living (i.e. social learning) are actually adaptive.[3]

"The Social Brain": Brain Evolution and Group Size

The Relationship between neocortex size and group size in primates

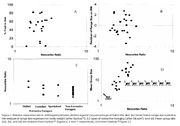

Comparing relative neocortex size, to various social and ecological factors. One should note that the power to detect an effect is very small here (n=29) and that the neocortex ratio is plotted logarithmically with a base of ten.

One way in which the social intelligence hypothesis has been investigated is through comparative research on how group size and brain size co-evolve. Even though brain size has been increasing over time in most species[4], researchers have tried to show that variation in brain size within animal orders can be predicted by group size. It is assumed that the overall group size is a good index of social complexity and the extent to which primates may have a fitness advantage in enhancing their "social cognition" (through any of the mechanisms outlined in the introduction). Primate brain evolution was first investigated, however the line of research has also been extended to other groups with mixed results.

Robin Dunbar famously posited "The Social Brain Hypothesis" (1998) summasing evidence for the comparative increase in brain size and social group size in simians. He showed that neither overall brain size, cerebrum size or neocortex size predicted group size, but the ratio of the neocortex against the rest of the brain is a very good predictor (r = .63; even when 8 other variables are controlled for).[5] He also included various measures ecological complexity (percentage of fruit in diet, extractive foraging and home range) to test if ecological explanations can also select for greater brain size. In his original analyses (Dunbar 1992, 1998) none did, but in later analyses with a greater sample size (and statistical power) a relatively smaller effect was shown for ecological variables (see below). However, Dunbar's analysis was mostly post hoc in that many reserachers did not know what was the best way to measure brain size, and 3 different methods are used by Dunbar for the neocortex alone (and only one was a significant predictor of intelligence). "Dunbars number" refers to the predicted group size of humans when looking only at their neocortex size, which is 150.

Dunbar has tended to argue that social complexity (in terms of hierarchies and quantity) as well as machiavellian intelligence (deception and coalition formation) as being important drivers of this effect, however, others have argued that social learning of efficient foraging strategies has been the principle selection driver. [6][7] It is neither not very clear whether researchers like Dunbar are arguing that a form of domain-free general intelligence evovles or a specialised form of social cognitive intelligence when looking at neocortex evolution.

The social brain hypothesis in non-primates

These findings have been extended to other taxa. In ungalates, the neocortex ratio correlated with level of sociality and the type of social system (soltary, monogamous, harem, large stable group), however the small sample size (n=38) for neocortex data meant that statistical techniques used to correct shared phylogeny (more related animals being more similar and having correlated features) could only be used for total brain size.[8] Total brain size (relative to body size) also correlates with habitat and social system, but not group size, sociality or diet. Group size did not correlate with neocortex size in any of the analyses, suggesting that in ungalates other factors are a better index of social complexity. In odontocete species, relative total brain size also correlates with pod (group) size. [9]

Do ecological factors not effect brain evolution?

One should note that the social intelligence hypothesis is not ecology free. Many researchers juxtapose ecological vs social evolutionary driving forces of intelligence, but the social intelligence hypothesis posists that access to environmental resources can be maximised through the evolution of intelligent behavior.[10]

Either way, one may expect that areas other than the neocortex may be important for other forms of evolution of intelligent behaviour in ecological contexsts (i.e. remembering the location of fruit trees), and indeed the hippocampus size has been found to vary with ranging area.[11] We would expect the hippocampus, which is involved in memory, rather than neocortex size to evolve with some of these ecological factors. When using a larger sample of primate species than the origina reports (e.g. Dunbar 1998), Robin Dunbar found that ecological factors do correlate with brain size measures, however things like diet (percentage of fruit) and habitat are weaker predictors than social factors. In addition, diet only significantly to contributes to overall brain size (r = .19, p = .01) and cerebrum (r = .16, p '= .16) measures, and not the neocortex, which suggests that it plays a role as a metabolic constraint on brain growth.[12] This is because brain tissue is costly, and species which can reduce the percentage of this energetically costly and fragile tissue will need to gather less food.[13]

Why does living in (larger) social groups lead to evolution in intelligent behavior?

Deception, coalition-formation and social cognition amongst primates, the drivers of brain evolution?

- Main article: Machiavellian intelligence

The machiavellian intelligence hypothesis posits that individuals abilties to exploit, decieve and out-maneuver others will lead to a competetive advantage to gaining resources within a group. Some researchers have gone as far to label social the social lives of primates as "poltical" in the sense to which power, hierarchy and social maneuvering plays a key role in access to resources such as females. [14] However, very little research has associated these behaviors with reproductive fitness, which is needed to show that sociality leads to selective pressure on intelligence. Some evidence exists, however, which is described below.

Dominance rank effects reproducitve performance in many taxa[15], however in primate species with larger neocortices, male social rank does not predict mating success as well, presumably because the larger neocortex of individuals allows lower ranking primates too use social methods such as deception to gain mates. [16] In addition, reported deception rate in the primatology literature very strongly (r = 0.74) predicts neocortex ratio, when the reported rate of deception is controlled for the "research effort" on a particular species. [17]

Some have criticised the evidence that primates decieve others as purely "anecdotal" and as being anthromorphic projects on behavior. Others have said that the evidence that primates form coalitions habitually is lacking. [18]

Social learning and its adaptive value

Social learning is a widespread skill amongst animals, however it varies in complexity across taxa, although research many speces other than primates is still in its infancy. There are varying views on its adaptive value, however, with the prevailing assumption that it is an adaptive skill being questioned by some. [19]

The social intelligence hypothesis and hominin evolution

Professor of early history at Reading University, Steve Mithen, believes that there are two key periods of human brain growth that contextualize the social intelligence hypothesis. The first was around two million years ago, when the brain more than doubled, from around 450cc to 1,000cc by 1.8 million years ago. Brain tissue is very expensive metabolically, so it must have served an important purpose. Mithen believes that this growth was because people were living in larger, more complex groups, and had to keep track of more people and relationships, which required a greater mental capacity and so a larger brain.[20]

The second growth in human brain size occurred between 600,000 and 200,000 years ago, when the brain reached its modern size. This growth is still not fully explained. Mithen’s believes that it is related to the evolution of language. Language is probably the most complex cognitive task we undertake. It is directly related to social intelligence because we mainly use language to mediate our social relationships.[20]

So social intelligence was a critical factor in brain growth, social and cognitive complexity co-evolve.[21]

Differences from intelligence

Professor Nicholas Humphrey points to a difference between intelligence and social intelligence. Some autistic children are extremely intelligent because they are very good at observing and memorising information, but they have low social intelligence. Similarly, chimpanzees are very adept at observation and and memorisation, sometimes better than humans, but may be regarded as less skilled in managing social and interpersonal relationships. What they lack is a theory of other people's minds. For a long time, the field was dominated by behaviorism, that is, the theory that one could understand animals including humans just by observing their behavior and finding correlations. But recent theories indicate that one must consider the inner structure behaviour.[1]

Both Nicholas Humphrey and Ross Honeywill believe that it is social intelligence, or the richness of our qualitative life, rather than our quantitative intelligence, that makes humans what they are; for example what it is like to be a human being living at the centre of the conscious present, surrounded by smells and tastes and feels and the sense of being an extraordinary metaphysical entity with properties which hardly seem to belong to the physical world. This is social intelligence.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Professor Nicholas Humphrey, London School of Economics - http://www.lse.ac.uk

- ↑ Humphrey, N. (1976) The Social Function of intellect. In Growing Points in ethology (eds P.P.G. Bateson & R.A> Hinde), pp.303-317. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press .

- ↑ e.g. Silk, J. (2007) The Adaptive value of sociality in mammalian groups. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 362, 539-559.

- ↑ Schultz, S. & Dunbar, R.I.M. (2006)Both social and ecological factors predict ungulate brain size. Proceedings of the Royal Society, 273, 207-215.

- ↑ Dunbar, R.I.M. (1998) The Social Brain Hypothesis. Evolutionary Anthropology, 178-190.

- ↑ Reader, S. M. & Laland, K. N. (2002) Social intelligence, innovation, and enhanced brain size in primates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science. 99, 4436–4441.

- ↑ Dunbar, R.I.M. (2007) Understandign primate brain evolution. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 362, 649-658.

- ↑ Schultz, S. & Dunbar, R.I.M (2006) Both social and ecologial factors predict ungalate brain size. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 273, 207-215.

- ↑ Marino, L. (1996) What can Dolpins tell us about primate evolution? Evolutionary Anthropology, 81-87.

- ↑ Dunbar, R.I.M, Shultz, S. (2007) Understanding primate brain evolution. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 362, 649-658.

- ↑ Barton, R.A. & Purvis, A. (1994) PRimate brains and ecology: Looking beneath the surface. In Anderson, J.R., Thierry, B. & Herrenschmidt, N. (eds). Current Primatology, pp. 1-12. Strasbourg: University of Stresbourg Press.

- ↑ Dunbar, R.I.M. (2007) Understandign primate brain evolution. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 362, 649-658.

- ↑ Aiello, L.C. & Wheeler, P. (1995) The Expensive-Tissue Hypothesis: The Brain and the Digestive System in Human and Primate Evolution. Current Anthropology, 36, 2, 199-221.

- ↑ de Waal, F. (1998) Chimpanzee Politics: Power and Sex among Apes. John Hopkins University Press.

- ↑ Pusey, A. & Packer, C. (1994) The Ecology of relationships. IN: Behavioural ecology (eds J. Krebs & N.B. Davies), pp. 254-283. 4th ed. Oxford: Blackwell.

- ↑ Pawlowski, B., Lowen, C. B. & Dunbar, R. I. M. (1998) Neocortex size, social skills and mating success in primates. Behaviour, 135, 357–368

- ↑ Byrne, R.W. & Corp, N. (2004) Neocortex size predicts deception rate in primates. Proceedings of the Royal Society London B, 271, 1693-1699.

- ↑ Barret, L. et al. (2007) Social brains, simple minds: does social complexity really require cognitive complexity? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 362, 561-575.

- ↑ Rieucau, G. & Giraldeau, L. (2011) Exploring the costs and benefits of social infomation use: an appraisal of current experimental evidence. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 366, 1567, 949-957.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Steven Mithen Professor in Archaeology, School of Archaeology, Geography and Environmental Science, University of Reading - http://www.reading.ac.uk/archaeology/about/staff/s-j-mithen.aspx

- ↑ Benoit Hardy-Vallée, The Philosophy of Social Cognition. 2008

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia (view authors). |