No edit summary |

|||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

Contemporary '''philosophical realism''' is the belief in a [[reality]] that is completely [[ontological]]ly independent of our conceptual schemes, linguistic practices, beliefs, etc. Philosophers who profess realism also typically believe that [[truth]] consists in a belief's [[correspondence theory of truth|correspondence]] to reality. We may speak of realism with respect to [[The problem of other minds|other minds]], the [[past]], the [[future]], [[Universal (metaphysics)|universals]], [[mathematics|mathematical entities]] (such as [[natural numbers]]), [[morality|moral categories]], the [[material world]], or even [[thought]]. |

Contemporary '''philosophical realism''' is the belief in a [[reality]] that is completely [[ontological]]ly independent of our conceptual schemes, linguistic practices, beliefs, etc. Philosophers who profess realism also typically believe that [[truth]] consists in a belief's [[correspondence theory of truth|correspondence]] to reality. We may speak of realism with respect to [[The problem of other minds|other minds]], the [[past]], the [[future]], [[Universal (metaphysics)|universals]], [[mathematics|mathematical entities]] (such as [[natural numbers]]), [[morality|moral categories]], the [[material world]], or even [[thought]]. |

||

| − | Realists tend to believe that whatever we believe now is only an approximation of reality and that every new observation brings us closer to understanding reality.<ref>Blackburn p. 188</ref> |

+ | Realists tend to believe that whatever we believe now is only an approximation of reality and that every new observation brings us closer to understanding reality.<ref>Blackburn p. 188</ref> In its Kantian sense, ''realism'' is contrasted with ''[[idealism]]''. In a contemporary sense, ''realism'' is contrasted with ''[[anti-realism]]'', primarily in the [[philosophy of science]]. |

| − | Realism is contrasted with [[anti-realism]]. |

||

== Debates about realism == |

== Debates about realism == |

||

| Line 12: | Line 11: | ||

In its Kantian sense, ''realism'' is contrasted with ''[[idealism]]'''. In a contemporary sense, ''realism'' is contrasted with ''[[anti-realism]]'', primarily in the [[philosophy of science]]. |

In its Kantian sense, ''realism'' is contrasted with ''[[idealism]]'''. In a contemporary sense, ''realism'' is contrasted with ''[[anti-realism]]'', primarily in the [[philosophy of science]]. |

||

| − | == |

+ | ===Platonic realism=== |

| + | {{Platonism}} |

||

| − | Both these disputes are often carried out relative to some specific area: one might, for example, be a realist about physical matter but an anti-realist about ethics. The high necessity of specifying the area in which the claim is made has been increasingly acknowledged in recent years. |

||

| + | [[Platonic realism]] is a [[philosophy|philosophical]] term usually used to refer to the idea of realism regarding the existence of [[universals (metaphysics)|universals]] or [[abstract object]]s after the [[Greek philosophy|Greek]] [[philosopher]] [[Plato]] (c. 427–c. 347 BC), a student of [[Socrates]]. As universals were considered by Plato to be [[Theory of Forms|ideal forms]], this stance is confusingly also called [[Platonic idealism]]. This should not be confused with [[Philosophical idealism|Idealism]], as presented by philosophers such as [[George Berkeley]]: as Platonic [[abstraction]]s are not spatial, temporal, or mental, they are not compatible with the latter Idealism's emphasis on mental existence. Plato's Forms include numbers and geometrical figures, making them a theory of [[mathematical realism]]; they also include the [[Form of the Good]], making them in addition a theory of [[ethical realism]].{{citation needed|date=June 2012}} |

||

| − | Increasingly these last disputes, too, are rejected as misleading, and some philosophers prefer to call the kind of realism espoused there "metaphysical realism," and eschew the whole debate in favour of simple "[[Naturalism (philosophy)|naturalism]]" or "natural realism", which is not so much a theory as the position that these debates are ill-conceived if not incoherent, and that there is no more to deciding what is ''really real'' than simply taking our words at face value. |

||

| + | ===The Scottish School of Common Sense Realism=== |

||

| − | Some realist philosophers prefer [[deflationary theory of truth|deflationary]] theories of truth to more traditional correspondence accounts. |

||

| + | {{main|Common Sense Realism}} |

||

| + | [[Scottish Common Sense Realism]] is a school of [[philosophy]] that sought to defend naive realism against philosophical paradox and [[scepticism]], arguing that matters of [[common sense]] are within the reach of common understanding and that common-sense beliefs even govern the lives and thoughts of those who hold non-commonsensical beliefs. It originated in the ideas of the most prominent members of the Scottish School of Common Sense, [[Thomas Reid]], [[Adam Ferguson]] and [[Dugald Stewart]], during the 18th century [[Scottish Enlightenment]] and flourished in the late 18th and early 19th centuries in Scotland and America.{{citation needed|date=June 2012}} |

||

| − | == Realism in logic and mathematics == |

||

| − | {{see|Philosophy of mathematics}} |

||

| + | Its roots can be found in responses to such philosophers as [[John Locke]], [[George Berkeley]] and [[David Hume]]. The approach was a response to the "ideal system" that began with Descartes' concept of the limitations of [[empirical evidence|sense experience]] and led Locke and Hume to a skepticism that called religion and the evidence of the senses equally into question. The common sense realists found skepticism to be absurd and so contrary to common experience that it had to be rejected. They taught that ordinary experiences provide intuitively certain assurance of the existence of the self, of real objects that could be seen and felt and of certain "first principles" upon which sound morality and religious beliefs could be established. Its basic principle was enunciated by its founder and greatest figure, Thomas Reid:<ref>Cuneo and Woudenberg, eds. ''The Cambridge companion to Thomas Reid'' (2004) p 85</ref> |

||

| − | ''Mathematical realism'', like realism in general, holds that mathematical entities exist independently of the human [[mind]]. Thus humans do not invent mathematics, but rather discover it, and any other intelligent beings in the universe would presumably do the same. In this point of view, there is really one sort of mathematics that can be discovered: [[Triangle]]s, for example, are real entities, not the creations of the human mind. |

||

| + | :"If there are certain principles, as I think there are, which the constitution of our nature leads us to believe, and which we are under a necessity to take for granted in the common concerns of life, without being able to give a reason for them--these are what we call the principles of common sense; and what is manifestly contrary to them, is what we call absurd.". |

||

| − | Many working mathematicians have been mathematical realists; they see themselves as discoverers of naturally occurring objects. Examples include [[Paul Erdős]] and [[Kurt Gödel]]. Gödel believed in an objective mathematical reality that could be perceived in a manner analogous to sense perception. Certain principles (e.g., for any two objects, there is a collection of objects consisting of precisely those two objects) could be directly seen to be true, but some conjectures, like the [[continuum hypothesis]], might prove undecidable just on the basis of such principles. Gödel suggested that quasi-empirical methodology could be used to provide sufficient evidence to be able to reasonably assume such a conjecture. |

||

| + | ===Naïve realism=== |

||

| − | Within realism, there are distinctions depending on what sort of existence one takes mathematical entities to have, and how we know about them. |

||

| + | [[Naïve realism]], also known as direct realism, is a [[philosophy of mind]] rooted in a [[common sense]] [[theory]] of [[perception]] that claims that the [[senses]] provide us with direct [[awareness]] of the external world. In contrast, some forms of [[idealism]] assert that no world exists apart from mind-dependent ideas and some forms of [[skepticism]] say we cannot trust our senses. The realist view is that [[Object (philosophy)|object]]s are composed of [[matter]], occupy [[space]] and have properties, such as size, shape, texture, smell, taste and colour, that are usually [[Perception|perceived]] correctly. We perceive them as they ''really'' are. Objects obey the laws of [[physics]] and retain all their properties whether or not there is anyone to observe them.<ref name=tok>[http://www.theoryofknowledge.info/naiverealism.html Naïve Realism], ''Theory of Knowledge.com''.</ref> |

||

| + | ===Scientific realism=== |

||

| − | ==Realism in physics== |

||

| + | [[Scientific realism]] is, at the most general level, the view that the world described by science is the real world, as it is, independent of what we might take it to be. Within [[philosophy of science]], it is often framed as an answer to the question "how is the success of science to be explained?" The debate over what the success of science involves centers primarily on the status of [[unobservables|unobservable entities]] apparently talked about by scientific [[theory|theories]]. Generally, those who are scientific realists assert that one can make reliable claims about unobservables (viz., that they have the same [[Ontology|ontological]] status) as observables. [[Analytical philosopher]]s generally have a commitment to scientific realism, in the sense of regarding the scientific method as a reliable guide to the nature of reality. The main alternative to scientific |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | realism is [[instrumentalism]].{{citation needed|date=June 2012}} |

||

| − | Realism in physics refers to the fact that any physical system must have its property defined, whether or not it is measured (or observed or not). However, Quantum Mechanics states it is not valid to say that a system has some property unless that property is measured. This implies that quantum systems exhibit a non-local behaviour. [[Bell's theorem]] proved that every [[Quantum mechanics|quantum theory]] must either violate [[Principle of locality|local realism]] or [[counterfactual definiteness]]. [[Physics]] up to the 19th century was always implicitly and sometimes explicitly taken to be based on philosophical realism. With the advent of [[quantum mechanics]] in the 20th century, it was noted that it is no longer possible to adhere local realism — that is, to both the [[principle of locality]] (that distant objects cannot affect local objects), and counterfactual definiteness, a form of ontological realism implicit in classical physics. This has given rise to a contentious debate of the [[interpretation of quantum mechanics]]. Although locality and 'realism' in the sense of counterfactual definiteness, are jointly false, it is possible to retain one of them. The majority of working physicists discard counterfactual definiteness in favor of locality, since non-locality is held to be contrary to relativity. The implications of this stance are rarely discussed outside of the microscopic domain. See, however, [[Schrödinger's cat]] for an illustration of the difficulties presented. It can also be argued that the counterfactual definiteness 'realism' of physics is a much more specific notion than general philosophical realism.<ref>"We examine the prevalent use of the phrase “local realism” in the context of Bell’s Theorem and associated experiments, with a focus on the |

||

| − | question: what exactly is the ‘realism’ in ‘local realism’ supposed to |

||

| − | mean?". [http://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/0607057 Norsen, T.''Against 'Realism' '']</ref> <!-- Editors, please read the Norsen paper to see why I have scare-quoted 'realism' --> |

||

| − | == |

+ | ===Aesthetic realism=== |

| + | [[Aesthetic realism]] may mean the claim that there are mind-independent aesthetic facts,<ref>{{Cite journal|journal=[[Mind (journal)|Mind]]|title=Review: The Metaphysics of Beauty|year=2004|volume=113|issue=449|pages=221-226}} {{Subscription required}}</ref> but in general discussions about art [[Realism (arts)|"Realism" and "realism"]] are complex terms that may have a number of different meanings. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| − | == References == |

||

| − | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| − | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | ==Other aspects== |

||

*[[Aesthetic Realism]], a philosophy founded by the American poet and critic Eli Siegel |

*[[Aesthetic Realism]], a philosophy founded by the American poet and critic Eli Siegel |

||

*[[Australian realism]] or Australian materialism, a 20th Century school of philosophy in Australia |

*[[Australian realism]] or Australian materialism, a 20th Century school of philosophy in Australia |

||

| Line 55: | Line 47: | ||

*[[Epistemological realism]], a subcategory of objectivism |

*[[Epistemological realism]], a subcategory of objectivism |

||

*[[Hyper-realism]] or Hyperreality, the inability of consciousness to distinguish reality from fantasy |

*[[Hyper-realism]] or Hyperreality, the inability of consciousness to distinguish reality from fantasy |

||

| + | *[[Legal realism]] |

||

*[[Mathematical realism]], a branch of philosophy of mathematics |

*[[Mathematical realism]], a branch of philosophy of mathematics |

||

*[[Moderate realism]], a position holding that there is no realm where universals exist |

*[[Moderate realism]], a position holding that there is no realm where universals exist |

||

*[[Modal realism]], a philosophy propounded by David Lewis, that possible worlds are as real as the actual world |

*[[Modal realism]], a philosophy propounded by David Lewis, that possible worlds are as real as the actual world |

||

*[[Moral realism]], the view in philosophy that there are objective moral values |

*[[Moral realism]], the view in philosophy that there are objective moral values |

||

| − | *[[Naive realism]], a common sense theory of perception |

||

*[[New realism (philosophy)]], a school of early 20th-century epistemology rejecting epistemological dualism |

*[[New realism (philosophy)]], a school of early 20th-century epistemology rejecting epistemological dualism |

||

*[[Organic realism]] or the Philosophy of Organism, the metaphysics of Alfred North Whitehead, now known as process philosophy |

*[[Organic realism]] or the Philosophy of Organism, the metaphysics of Alfred North Whitehead, now known as process philosophy |

||

| Line 65: | Line 57: | ||

*[[Quasi-realism]], an expressivist meta-ethical theory which asserts that though our moral claims are projectivist we understand them in realist terms |

*[[Quasi-realism]], an expressivist meta-ethical theory which asserts that though our moral claims are projectivist we understand them in realist terms |

||

*[[Representative realism]], the view that we cannot perceive the external world directly |

*[[Representative realism]], the view that we cannot perceive the external world directly |

||

| + | *[[Speculative realism]] |

||

| − | *[[Scientific realism]], the view that the world described by science is the real world |

||

*[[Transcendental realism]], a concept implying that individuals have a perfect understanding of the limitations of their own minds |

*[[Transcendental realism]], a concept implying that individuals have a perfect understanding of the limitations of their own minds |

||

*[[Truth-value link realism]], a metaphysical concept explaining how to understand parts of the world that are apparently cognitively inaccessible |

*[[Truth-value link realism]], a metaphysical concept explaining how to understand parts of the world that are apparently cognitively inaccessible |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | * [[Analytic philosophy]] |

||

| + | * [[Objectivism (Ayn Rand)|Objectivism]] |

||

| + | * [[Philosophy of social science]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | * [[Problem of future contingents]] |

||

===Critics=== |

===Critics=== |

||

* [[Constructivist epistemology]] |

* [[Constructivist epistemology]] |

||

| − | ==References |

+ | ==References== |

| ⚫ | |||

| − | <References/> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Further reading== |

||

| + | |||

==Key texts== |

==Key texts== |

||

===Books=== |

===Books=== |

||

| Line 86: | Line 89: | ||

*Ben-Ze'ev, A. (1993). The perceptual system: A philosophical and psychological perspective. New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing. |

*Ben-Ze'ev, A. (1993). The perceptual system: A philosophical and psychological perspective. New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing. |

||

*Bhaskar, R. (2002). From science to emancipation: Alienation and the actuality of enlightenment. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. |

*Bhaskar, R. (2002). From science to emancipation: Alienation and the actuality of enlightenment. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

*Burr, V. (1998). Overview: Realism, relativism, social constructionism and discourse. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. |

*Burr, V. (1998). Overview: Realism, relativism, social constructionism and discourse. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. |

||

*Chesni, Y., & Zenk, J. P. (1987). Dialectical realism: Towards a philosophy of growth. Palo Alto, CA: The Live Oak Press. |

*Chesni, Y., & Zenk, J. P. (1987). Dialectical realism: Towards a philosophy of growth. Palo Alto, CA: The Live Oak Press. |

||

| Line 165: | Line 169: | ||

===Papers=== |

===Papers=== |

||

| − | *[http://scholar.google.com/scholar?sourceid=mozclient&num=50&scoring=d&ie=utf-8&oe=utf-8&q= |

+ | *[http://scholar.google.com/scholar?sourceid=mozclient&num=50&scoring=d&ie=utf-8&oe=utf-8&q=aesthetic+realism Google Scholar] |

===Dissertations=== |

===Dissertations=== |

||

Latest revision as of 19:29, 31 October 2013

Assessment |

Biopsychology |

Comparative |

Cognitive |

Developmental |

Language |

Individual differences |

Personality |

Philosophy |

Social |

Methods |

Statistics |

Clinical |

Educational |

Industrial |

Professional items |

World psychology |

Philosophy Index: Aesthetics · Epistemology · Ethics · Logic · Metaphysics · Consciousness · Philosophy of Language · Philosophy of Mind · Philosophy of Science · Social and Political philosophy · Philosophies · Philosophers · List of lists

Contemporary philosophical realism is the belief in a reality that is completely ontologically independent of our conceptual schemes, linguistic practices, beliefs, etc. Philosophers who profess realism also typically believe that truth consists in a belief's correspondence to reality. We may speak of realism with respect to other minds, the past, the future, universals, mathematical entities (such as natural numbers), moral categories, the material world, or even thought.

Realists tend to believe that whatever we believe now is only an approximation of reality and that every new observation brings us closer to understanding reality.[1] In its Kantian sense, realism is contrasted with idealism. In a contemporary sense, realism is contrasted with anti-realism, primarily in the philosophy of science.

Debates about realism

Despite the seeming straightforwardness of the realist position, in the history of philosophy there has been continuous debate about what is real. In addition, there has been significant evolution in what is meant by the term "real".

The oldest use of the term comes from medieval interpretations and adaptations of Greek philosophy. In this medieval scholastic philosophy, however, "realism" meant something different -- indeed, in some ways almost opposite -- from what it means today. In medieval philosophy, realism is contrasted with "conceptualism" and "nominalism". The opposition of realism and nominalism developed out of debates over the problem of universals. Universals are terms or properties that can be applied to many things, rather than denoting a single specific individual--for example, red, beauty, five, or dog, as opposed to "Socrates" or "Athens". Realism in this context holds that universals really exist, independently and somehow prior to the world; it is associated with Plato. Conceptualism holds that they exist, but only in the mind, Moderate Realism holds that they exist, but only insofar as they are instantiated in specific things; they do not exist separately from the specific thing. Nominalism holds that universals do not "exist" at all; they are no more than words we use to describe specific objects, they do not name anything. This particular dispute over realism is largely moot in contemporary philosophy, and has been for centuries.

In its Kantian sense, realism is contrasted with idealism'. In a contemporary sense, realism is contrasted with anti-realism, primarily in the philosophy of science.

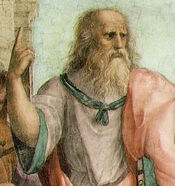

Platonic realism

| Platonism |

| Platonic idealism |

| Platonic realism |

| Middle Platonism |

| Neoplatonism |

| Articles on Neoplatonism |

| Platonic epistemology |

| Socratic method |

| Socratic dialogue |

| Theory of forms |

| Platonic doctrine of recollection |

| Individuals |

| Plato |

| Socrates |

| Discussions of Plato's works |

| Dialogues of Plato |

| Plato's metaphor of the sun |

| Analogy of the divided line |

| Allegory of the cave

|

Platonic realism is a philosophical term usually used to refer to the idea of realism regarding the existence of universals or abstract objects after the Greek philosopher Plato (c. 427–c. 347 BC), a student of Socrates. As universals were considered by Plato to be ideal forms, this stance is confusingly also called Platonic idealism. This should not be confused with Idealism, as presented by philosophers such as George Berkeley: as Platonic abstractions are not spatial, temporal, or mental, they are not compatible with the latter Idealism's emphasis on mental existence. Plato's Forms include numbers and geometrical figures, making them a theory of mathematical realism; they also include the Form of the Good, making them in addition a theory of ethical realism.[citation needed]

The Scottish School of Common Sense Realism

- Main article: Common Sense Realism

Scottish Common Sense Realism is a school of philosophy that sought to defend naive realism against philosophical paradox and scepticism, arguing that matters of common sense are within the reach of common understanding and that common-sense beliefs even govern the lives and thoughts of those who hold non-commonsensical beliefs. It originated in the ideas of the most prominent members of the Scottish School of Common Sense, Thomas Reid, Adam Ferguson and Dugald Stewart, during the 18th century Scottish Enlightenment and flourished in the late 18th and early 19th centuries in Scotland and America.[citation needed]

Its roots can be found in responses to such philosophers as John Locke, George Berkeley and David Hume. The approach was a response to the "ideal system" that began with Descartes' concept of the limitations of sense experience and led Locke and Hume to a skepticism that called religion and the evidence of the senses equally into question. The common sense realists found skepticism to be absurd and so contrary to common experience that it had to be rejected. They taught that ordinary experiences provide intuitively certain assurance of the existence of the self, of real objects that could be seen and felt and of certain "first principles" upon which sound morality and religious beliefs could be established. Its basic principle was enunciated by its founder and greatest figure, Thomas Reid:[2]

- "If there are certain principles, as I think there are, which the constitution of our nature leads us to believe, and which we are under a necessity to take for granted in the common concerns of life, without being able to give a reason for them--these are what we call the principles of common sense; and what is manifestly contrary to them, is what we call absurd.".

Naïve realism

Naïve realism, also known as direct realism, is a philosophy of mind rooted in a common sense theory of perception that claims that the senses provide us with direct awareness of the external world. In contrast, some forms of idealism assert that no world exists apart from mind-dependent ideas and some forms of skepticism say we cannot trust our senses. The realist view is that objects are composed of matter, occupy space and have properties, such as size, shape, texture, smell, taste and colour, that are usually perceived correctly. We perceive them as they really are. Objects obey the laws of physics and retain all their properties whether or not there is anyone to observe them.[3]

Scientific realism

Scientific realism is, at the most general level, the view that the world described by science is the real world, as it is, independent of what we might take it to be. Within philosophy of science, it is often framed as an answer to the question "how is the success of science to be explained?" The debate over what the success of science involves centers primarily on the status of unobservable entities apparently talked about by scientific theories. Generally, those who are scientific realists assert that one can make reliable claims about unobservables (viz., that they have the same ontological status) as observables. Analytical philosophers generally have a commitment to scientific realism, in the sense of regarding the scientific method as a reliable guide to the nature of reality. The main alternative to scientific realism is instrumentalism.[citation needed]

Aesthetic realism

Aesthetic realism may mean the claim that there are mind-independent aesthetic facts,[4] but in general discussions about art "Realism" and "realism" are complex terms that may have a number of different meanings.

Other aspects

- Aesthetic Realism, a philosophy founded by the American poet and critic Eli Siegel

- Australian realism or Australian materialism, a 20th Century school of philosophy in Australia

- Constructive realism, a philosophy of science

- Cornell realism, a view in meta-ethics associated with the work of Richard Boyd and others

- Critical realism, a philosophy of perception concerned with the accuracy of human sense-data

- Depressive realism

- Direct realism, a theory of perception

- Entity realism, a philosophical position within scientific realism

- Epistemological realism, a subcategory of objectivism

- Hyper-realism or Hyperreality, the inability of consciousness to distinguish reality from fantasy

- Legal realism

- Mathematical realism, a branch of philosophy of mathematics

- Moderate realism, a position holding that there is no realm where universals exist

- Modal realism, a philosophy propounded by David Lewis, that possible worlds are as real as the actual world

- Moral realism, the view in philosophy that there are objective moral values

- New realism (philosophy), a school of early 20th-century epistemology rejecting epistemological dualism

- Organic realism or the Philosophy of Organism, the metaphysics of Alfred North Whitehead, now known as process philosophy

- Platonic realism, a philosophy articulated by Plato, positing the existence of universals

- Quasi-realism, an expressivist meta-ethical theory which asserts that though our moral claims are projectivist we understand them in realist terms

- Representative realism, the view that we cannot perceive the external world directly

- Speculative realism

- Transcendental realism, a concept implying that individuals have a perfect understanding of the limitations of their own minds

- Truth-value link realism, a metaphysical concept explaining how to understand parts of the world that are apparently cognitively inaccessible

See also

- Analytic philosophy

- Objectivism

- Philosophy of social science

- Principle of bivalence

- Problem of future contingents

Critics

References

Further reading

Key texts

Books

- Alloy, L. B., & Abramson, L. Y. (1988). Depressive realism: Four theoretical perspectives. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Almeder, R. F. (1992). Blind realism: An essay on human knowledge and natural science. Lanham, MD, England: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Anderson, D. L. (2007). Consciousness and realism. Charlottesville, VA: Imprint Academic.

- Appleby, R. S. (2006). Conclusion: Reconciliation and Realism. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

- Arabatzis, T. (2007). Conceptual change and scientific realism: Facing Kuhn's challenge. New York, NY: Elsevier Science.

- Bain, A. (1880). Abstraction--The abstract idea. New York, NY: D Appleton & Company.

- Baker, L. R. (1995). Explaining attitudes: A practical approach to the mind. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Ben-Ze'ev, A. (1993). The perceptual system: A philosophical and psychological perspective. New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing.

- Bhaskar, R. (2002). From science to emancipation: Alienation and the actuality of enlightenment. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Blackburn, Simon (2005). Truth: A Guide, Oxford University Press, Inc.

- Burr, V. (1998). Overview: Realism, relativism, social constructionism and discourse. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Chesni, Y., & Zenk, J. P. (1987). Dialectical realism: Towards a philosophy of growth. Palo Alto, CA: The Live Oak Press.

- Collier, A. (1998). Language, practice and realism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Davies, B. (1998). Psychology's subject: A commentary on the relativism/realism debate. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Dennett, D. C. (2006). "Real patterns". New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Dolev, Y. (2007). Time and realism: Metaphysical and antimetaphysical perspectives. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Doris, J. M., & Plakias, A. (2008). How to argue about disagreement: Evaluative diversity and moral realism. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Eucken, R., & Phelps, M. S. (1880). Realism--Idealism. New York, NY: D Appleton & Company.

- Fodor, J. (1991). Methodological solipsism considered as a research strategy in cognitive psychology. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Funder, D. C. (2001). Three trends in current research on person perception: Positivity, realism, and sophistication. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Harrison, S. (1989). A new visualization of the mind-brain relationship: Naive realism transcended. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press.

- Held, B. S. (1995). Back to reality: A critique of postmodern theory in psychotherapy. New York, NY: W W Norton & Co.

- Held, B. S. (2007). Introduction. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Held, B. S. (2007). Ontological point 2: A middle-ground realist ontology? Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Held, B. S. (2007). Ontological point 3: An ontology of situated agency and transcendence. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Held, B. S. (2007). Psychology's interpretive turn: The search for truth and agency in theoretical and philosophical psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Held, B. S. (2007). Situated warrant: A middle-ground realist epistemology? Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Ladd, G. T. (1897). Idealism and realism. New York, NY: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Leiter, B. (2008). Against convergent moral realism: The respective roles of philosophical argument and empirical evidence. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Manicas, P. T. (2006). A realist philosophy of social science: Explanation and understanding. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Miller, A. (2006). Realism and antirealism. New York, NY: Clarendon Press/Oxford University Press.

- Montero, M. (1998). The perverse and pervasive character of reality: Some comments on the effects of monism and dualism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Niiniluoto, I. (1994). Scientific realism and the problem of consciousness. Hillsdale, NJ, England: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Orange, D. M. (1992). Subjectivism, relativism, and realism in psychoanalysis. Hillsdale, NJ, England: Analytic Press, Inc.

- Pawson, R., & Tilley, N. (1997). An introduction to scientific realist evaluation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Pawson, R., & Tilley, N. (1997). Realistic evaluation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Perry, R. B. (1912). A realistic theory of knowledge. New York, NY: Longmans, Green and Co.

- Perry, R. B. (1912). A realistic theory of mind. New York, NY: Longmans, Green and Co.

- Plakias, A., & Doris, J. M. (2008). How to find a disagreement: Philosophical diversity and moral realism. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Potter, J. (1998). Fragments in the realization of relativism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Raftopoulos, A. (2005). Perceptual Systems and a Viable Form of Realism. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers.

- Schwegler, A., & Seelye, J. H. (1856). Idealism and realism. New York, NY: D Appleton & Company.

- Strawson, G. (1994). Mental reality. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Strawson, P. F. (2002). Perception and its objects. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Suppe, F. (1989). The semantic conception of theories and scientific realism. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- van Hezewijk, R. (1995). The importance of being realist. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Co.

- Whately, R. (1854). Of realism. Louisville, KY: Morton & Griswold.

Papers

Additional material

Books

- Bloomfield, P. (2008). Disagreement about disagreement. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Boghossian, P. A., & Velleman, J. D. (1997). Physicalist theories of colors. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Bradley, F. H. (1922). Essay IX: A note on analysis. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Bradley, F. H. (1922). Essay VIII: Some remarks on absolute truth and on probability. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Brown, S. D., Pujol, J., & Curt, B. C. (1998). As one in a web? Discourse, materiality and the place of ethics. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Burkitt, I. (1998). Relations, communication and power. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Ltd.

- Chow, S. L. (1995). Criticisms of experimentation revisited. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Co.

- Foster, D. (1998). Across the S-S divide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Hamilton, E. J. (1899). Realism and nominalism. Seattle, WA: Lowman and Hanford.

- Hamilton, W., Mansel, H. L., & Veitch, J. (1859). Lecture XXI. The presentative faculty--I. Perception--Reid's historical view of the theories of perception. Boston, MA: Gould and Lincoln.

- Hamilton, W., Mansel, H. L., & Veitch, J. (1859). Lecture XXIII. The presentative faculty--I. Perception--Was Reid a natural realist? Boston, MA: Gould and Lincoln.

- Hamilton, W., Mansel, H. L., & Veitch, J. (1859). Lecture XXV. The presentative faculty--I. Perception--Objections to the doctrine of natural realism. Boston, MA: Gould and Lincoln.

- Hamilton, W., Mansel, H. L., & Veitch, J. (1863). Lecture XXIV. The presentative faculty--I. Perception--The distinction of perception proper from sensation proper. Boston, MA: Gould and Lincoln.

- Hamilton, W., Mansel, H. L., & Veitch, J. (1863). Lecture XXV. The presentative faculty--I. Perception--Objections to the doctrine of natural realism. Boston, MA: Gould and Lincoln.

- Hardy, A. G. (1988). Psychology and the critical revolution. Guiderland, NY: James Publications.

- Katz, S. (1987). Is Gibson a relativist? New York, NY: St Martin's Press.

- Loeb, D. (2008). Moral incoherentism: How to pull a metaphysical rabbit out of a semantic hat. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Loeb, D. (2008). Reply to Gill and Sayre-McCord. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Marras, A. (2005). Commonsense Refutations of Eliminativism. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Morawski, J. (1998). The return of phantom subjects? Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Muller, F. M. (1887). On Kant's philosophy. New York, NY: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Murdoch, J. (1842). Pantheistic philosophy. Hartford, CT: John C Wells.

- Robinson, W. S. (1999). Evolution and self-evidence. Florence, KY: Taylor & Frances/Routledge.

- Royce, J. (1900). The independent beings: A critical examination of realism. New York, NY: MacMillan Co.

- Royce, J. (1900). Realism and mysticism in the history of thought. New York, NY: MacMillan Co.

- Royce, J. (1900). The unity of being, and the mystical interpretation. New York, NY: MacMillan Co.

- Sayre-McCord, G. (2008). Moral semantics and empirical inquiry. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Seigfried, C. H. (1993). The world we practically live in. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Sharpe, R. A. (1990). Making the human mind. Florence, KY: Taylor & Frances/Routledge.

- Stankov, L., & Kleitman, S. (2008). Processes on the borderline between cognitive abilities and personality: Confidence and its realism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Tuomela, R. (1994). The fate of folk psychology. Hillsdale, NJ, England: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Walter, J. E. (1879). The perception of extension by the sense of touch. Boston, MA: Estes and Lauriat.

- Walter, J. E. (1879). The true nature and process of our knowledge of matter. Boston, MA: Estes and Lauriat.

Papers

Dissertations

- Biehl, J. S. (2003). Immoral psychology: The cognitivist's conundrum. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences.

- Chase, K. S. (1981). Romance, realism, and the psychological aspect of the mid-Victorian novel: Dissertation Abstracts International.

- Grubbs, J. (1998). Real world, real conversations: Communication in an increasingly parasocial and pararealistic environment. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences.

- Huemer, M. (1999). A direct realist account of perceptual awareness. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences.

- Hulbert, M. C. (1993). Ideas as acts of perception: A direct realist interpretation of Descartes' theory of sense perception: Dissertation Abstracts International.

- Nlandu, T. (1997). Reality, perceptual experience, and cognition: A study in Charles Sanders Peirce's philosophy of mind. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences.

- Power, N. P. (1996). Intentional realism, instrumentalism and the future of folk psychology. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences.

- Pusch, D. (1996). The relationships between sociotropic and autonomous personality styles and perceptual biases in dysphoric and nondysphoric university students. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering.

- Ruttanachun, N. (1999). Style discrimination of non-art-trained adults: Decentration capacity and attention to manipulated visual elements. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences.

- Sabates, M. H. (1998). Mental causation: Property parallelism as answer to the problem of exclusion. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences.

- Scales, S. J. (1996). Values in ethics and science: A case against objective moral realism. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences.

- Schuber, S. P. (1977). From romanticism to realism: The intrusion of reality in Byron's Don Juan and Flaubert's Madame Bovary: Dissertation Abstracts International.

- Webster, S. (1995). The rhetoric of realism: American psychology and American literature, 1860-1910. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering.

- Woudzia, L. A. (1997). Psychological realism and the simulation theory of belief attribution. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences.

- Ziomek, R. L. (1979). An analysis of the relationships between philosophical attitudes and personality characteristics: Dissertation Abstracts International.

External links

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry

- An experimental test of non-local realism. Physics research paper in Nature which gives negative experimental results for certain classes of realism in the sense of physics.

Logic | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

* Portal

| ||||||||||||||||||||

- redirectTemplate:Philosophy

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia (view authors). |