(Created page with "{{Biopsy}} {{Infobox embryology | Name = Paramesonephric duct | Latin = ductus paramesonephricus | GraySubject = 252 | GrayPage = 1206 | Image ...") |

m (Dr Joe Kiff moved page Paramesonephric duct to Paramesonephric ducts) |

Latest revision as of 15:43, 13 October 2013

Assessment |

Biopsychology |

Comparative |

Cognitive |

Developmental |

Language |

Individual differences |

Personality |

Philosophy |

Social |

Methods |

Statistics |

Clinical |

Educational |

Industrial |

Professional items |

World psychology |

Biological: Behavioural genetics · Evolutionary psychology · Neuroanatomy · Neurochemistry · Neuroendocrinology · Neuroscience · Psychoneuroimmunology · Physiological Psychology · Psychopharmacology (Index, Outline)

| Paramesonephric duct | |

|---|---|

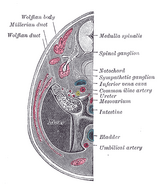

| Urogenital sinus of female human embryo of eight and a half to nine weeks old. | |

| Tail end of human embryo, from eight and a half to nine weeks old. | |

| Latin | ductus paramesonephricus |

| Gray's | subject #252 1206 |

| Carnegie stage | 17 |

| Precursor | Intermediate mesoderm |

| Code | TE E5.7.2.3.0.0.3 |

| MeSH | Mullerian+Ducts |

Müllerian ducts (or paramesonephric ducts) are paired ducts of the embryo that run down the lateral sides of the urogenital ridge and terminate at the Müllerian eminence in the primitive urogenital sinus. In the female, they will develop to form the Fallopian tubes, uterus, cervix, and the upper one-thirdd of the vagina;[1] in the male, they are lost. These ducts are made of tissue of mesodermal origin.[2]

Development

Müllerian duct (blue) develops in females (middle image) and degenerates in males of certain species(bottom).

The female reproductive system is composed of two embryological segments: the urogenital sinus and the Müllerian ducts. The two are conjoined at the Müllerian tubercle.[3] Müllerian ducts are present on the embryo of both sexes.[4] Only in females do they develop into reproductive organs. They degenerate in males of certain species, but the adjoining Wolffian ducts develop into male reproductive organs. The sex based differences in the contributions of the Müllerian ducts to reproductive organs is based on the presence, and degree of presence, of Müllerian inhibiting factor.

During the formation of the urinary system, the Müllerian ducts are formed. A new pair of Müllerian (paramesonephric) ducts are formed just lateral to the mesonephric ducts in both female and male embryos during the 6th week of development of the urinary system. During this time the germ cells migrate from the yolk sac to the mesenchyme of the dorsal body wall. These ducts are formed by the craniocaudal invagination of a ribbon of thickened coelomic epithelium that extends from the third thoracic segment caudally to the posterior wall of the urogenital sinus. The caudal tips of the Müllerian ducts then begin to grow in order to connect with the undeveloped pelvic urethra that is located just medial to the openings of the right and left mesonephric ducts. The tips of the two Müllerian ducts stick to each other just before they contact the undeveloped pelvic urethra. A funnel-shaped opening can be noted at the cranial ends of the Müllerian ducts into the coelom.

Regulation of development

The development of the Müllerian ducts is controlled by the presence or absence of "AMH", or Anti-Müllerian hormone (also known as "MIF" for "Müllerian-inhibiting factor", or "MIH" for "Müllerian-inhibiting hormone").[5]

| Male embryogenesis | The testes produce AMH and as a result the development of the Müllerian ducts is inhibited. | Disturbances can lead to persistent Müllerian duct syndrome. | The ducts disappear except for the vestigial vagina masculina and the appendix testis. |

| Female embryogenesis | The absence of AMH results in the development of female reproductive organs, as noted above. | Disturbance in the development may result in uterine absence (Müllerian agenesis) or uterine malformations. | The ducts develop into the upper vagina, cervix, uterus and oviducts. |

Function

In females, the Müllerian ducts give rise to the fallopian tubes, uterus, and upper portion of the vagina, while the mesonephric ducts degenerate due to the absence of male androgens. In contrast, the Müllerian ducts begin to proliferate and differentiate in a cranial-caudal progression to form the aforementioned structures. During this time, the single-layered Müllerian duct epithelium differentiates into other structures, ranging from the ciliated columnar epithelium in the fallopian tube to stratified squamous epithelium in the vagina.[6]

The Müllerian ducts and the mesonephric ducts share a majority of the same mesenchyme due to Hox gene expression. The genes expressed play a critical role in mediating the regional characterization of structures found along the cranial-caudal axis of the female reproductive tract.

Anti-Müllerian Hormone

Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), or Müllerian-inhibiting substance, is a glycoprotein hormone that is secreted by pre- Sertoli cells in males as they begin their morphologic differentiation in response to SRY expression. AMH is a member of the TGF-B family and is expressed only by Sertoli cells. AMH begins to be secreted by Sertoli cells around week 8, which in turn causes the Müllerian ducts to regress very rapidly between the 8th and 10th weeks. However, small Müllerian ducts can still be identified, and the remnants can be detected in the adult male, located in the appendix testis, a small cap of tissue associated with the testis. Remnants of the Müllerian ducts can also be found in the prostatic utricle, an expansion of the prostatic urethra.

AMH receptor-type II (AMHR-II), also known as Misr-II, causes AMH to act indirectly on mesenchymal cells surrounding the Müllerian ducts rather than acting directly on the epithelium of the duct.[6] This receptor activation induces the ducts to regress. The importance of mesenchyme-to-epithelial signaling is to maintain AMHR-II expression in the mesenchyme. In the absence of the Wnta7a within the duct epithelium as the ducts regress, ductal AMHR-II expression is lost, and residual Müllerian ducts would be retained in males, throwing off the urogenital system.

Persistent Müllerian duct syndrome, including cryptorchidism (undescended testis) or ectopic testis with inguinal hernias, have been identified in human males due to AMH and AMHR-II gene mutations. Recent studies have revealed another AMH receptor group, AMH receptor-type I (AMHR-I), based on the AMH being a TgfB/Bmp family member. Recent studies have shown that ALK2, Alk3 (or Bmpr 1a) and Alk6 all serve as AMHR-I receptors. When these receptors are blocked or knocked out in mice within the Müllerian duct mesenchyme, AMH-induced Müllerian duct regression is lost.

Mutations in AMH

Individuals that are 46, Xy and have been tested positive for mutations in their AMH or AMH receptor genes have been known to exhibit features typical of that which are exhibited in persistent müllerian duct syndrome due to the fact that the müllerian ducts fail to regress. When this happens the individuals develop structures that are derived from the müllerian duct, and also structures that are derived from the mesonephric duct. A male that has persistent müllerian duct syndrome may have a cervix, uterus and fallopian tubes as well as vas differentia along with male external genitalia. The female organs are in the correct anatomical position but the position of the testis varies. On average, 60% to 70% both testes will lie in the normal position and as for the ovaries about 20% to 30% of the time, one of the testis will lie within the inguinal hernial sac while in other cases the testes will lie within the same inguinal hernia sac. However whenever an individual exhibits persistent müllerian duct syndrome the vasa deferentia will run along the lateral sides of the uterus.[6]

Müllerian duct anomalies

Anomalies that develop within the müllerian duct system continue to puzzle and fascinate obstetricians and gynecologist. The müllerian ducts play a critical role in the female reproductive tract and differentiate to form the fallopian tubes, uterus, superior vagina as well as the uterine cervix. Many types of disorders can occur when this system is disrupted ranging from uterine and vagina agenises to the duplication of unwanted cells of the uterus and vagina. Müllerian malformations are usually related to abnormalities of the renal and axial skeletal system.[6] Malfunction in the ovaries and age onset abnormalaites can also be associated with most müllerian ducts. Most abnormalities are often recognized once the external genitalia is no longer masked and the internal reproductive organ abnormalities become revealed. Due to a very broad range of anomalies it is very difficult to diagnose müllerian duct anomalies.[7][7]

Management

Due to improved surgical instruments and technique women with müllerian duct anomalies can have normal sexual relations. Through the use of Vecchietti and Mclndoe procedures women can carry out their sexual activity.[7] On another note, many other surgical advances have tremendously improved fertility chances as wells as obstetric outcomes. Assisted reproductive technology makes it possible for some women that have müllerian duct anomalies to conceive and give birth to healthy babies.

Eponym

They are named after Johannes Peter Müller, a physiologist who described these ducts in his text "Bildungsgeschichte der Genitalien" in 1830.

Additional images

See also

- Defeminization

- prostatic utricle

- List of homologues of the human reproductive system

- Sexual differentiation

References

- ↑ Sizonenko, P.C. Human Sexual Differentiation. URL accessed on 2008-09-04.

- ↑ Hashimoto R (2011-07-27). Development of the human Müllerian duct in the sexually undifferentiated stage. The Anatomical Record Part A: Discoveries in Molecular, Cellular, and Evolutionary Biology 272 (2): 514–9.

- ↑ Yasmin Sajjad (2011-07-27). Development of the genital ducts and external genitalia in the early human embryo. The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research 36 (5): 929–937.

- ↑ (2011-07-27) Normal male sexual differentiation and aetiology of disorders of sex development. Male Reproductive Endocrinology 25 (2): 221–238.

- ↑ (2011-07-27) Expression of anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) in the equine testis. Theriogenology 69 (5): 624–631.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Schoenwolf, Gary C. (2008). Larsen’s Human Embryology, 509, 510504, 518, 520, Churchill Livingstone.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Amesse, Ibrahim Mullerian Duct Anomalies. URL accessed on 2012-11-29.

External links

- How the Body Works / Sex Development / Sexual Differentiation / Duct Differentiation - The Hospital for Sick Children (GTA - Toronto, Ontario, Canada)

- Mullerian Duct Anomalies

- [Müllerian duct

Prenatal development/mammalian embryogenesis - Development of the urinary and reproductive organs | |

|---|---|

| General Urinary/Reproductive system |

Cloacal membrane - Cloaca - Urethral groove - Urogenital sinus - Urachus - Urogenital folds |

| Kidney development |

Nephrogenic cord - Nephrotome - Pronephros - Mesonephros (Mesonephric tubules) |

| Fetal genital development - primarily internal |

Gonadal ridge - Sex cord (Cortical cords, Testis cords) |

| Primarily external |

Genital tubercle - Phallus - Labioscrotal folds |

|

see also list of homologues of the human reproductive system | |

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia (view authors). |