No edit summary |

|||

| (29 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{PhilPsy}} |

{{PhilPsy}} |

||

| + | [[Image:Descartes mind and body.gif|thumb|200px|right|[[René Descartes]]' illustration of brain anatomy and physiology. Inputs are passed on by the sensory organs to the [[pineal gland]] in the brain and from there to the motor nerves. At the pineal gland, the nerve processes affect the mind, an immaterial spirit, in accordance with Descartes' [[mind/body dualism]]. The mind can also affect the pineal gland, thereby directing the processes of the motor nerves. From Descartes (1664).]] |

||

| − | The '''mind-body problem''' |

+ | The '''mind-body problem''' can be stated as, "What is the basic relationship between the mental and the physical?" For the sake of simplicity, we can state the problem in terms of mental and physical events: "What is the basic relationship between mental events and physical events?" It could also be stated in terms of the relation between mental and physical states and/or processes, or between the brain and [[consciousness]]. |

| ⚫ | There are three basic metaphysical positions: mental and physical events are totally different, and cannot be reduced to each other ([[dualism]]); mental events are to be reduced to physical events ([[materialism]]); and physical events are to be reduced to mental events ([[idealism]]). To put it in terms of what exists "ultimately," we could say that according to dualism, both ''mental'' and ''physical'' events exist ultimately; according to materialism, only ''physical'' events exist ultimately; and according to idealism, only ''mental'' events exist ultimately. Materialism and idealism are both varieties of [[monism]], and of monism there are two further varieties, namely [[dual-aspect monism]] and [[neutral monism]]. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | The absence of an empirically identifiable meeting point between the non-physical mind and the physically extended body has proven problematic to dualism and many modern philosophers of mind maintain that the mind is not something separate from the body.<ref name="Kim1">{{cite book |

||

| − | If the mind is not seen as a "mysterious" substance, and it is assumed there are only ''mental events'' and that "the mind" is no more than a series of mental events, then it is possible to inquire about the relation between mind and body in terms of the relation between mental events and physical events. One can ask: are mental events ''completely different'' from physical events, so that you can't explain what mental events are in terms of physical events; or are mental events somehow explainable as being identical with certain physical events? For example, when John feels a pain, a mental event is occurring; is that pain identical to something that is physically occurring in John's brain, such as the firing of some special group of neurons? |

||

| + | | last = Kim |

||

| + | | first = J. |

||

| + | - |

||

| + | | editor = Honderich, Ted |

||

| + | |||

| + | - |

||

| + | | others = |

||

| + | |||

| + | - |

||

| + | | title = Problems in the Philosophy of Mind. Oxford Companion to Philosophy |

||

| + | |||

| + | - |

||

| + | | year = 1995 |

||

| + | |||

| + | - |

||

| + | | publisher = Oxford University Press |

||

| + | |||

| + | - |

||

| + | | location = Oxford |

||

| + | |||

| + | - |

||

| + | | id = |

||

| + | |||

| + | - |

||

| + | | doi = |

||

| + | |||

| + | - |

||

| + | }} <!--Kim, J., "Problems in the Philosophy of Mind". ''Oxford Companion to Philosophy''. Ted Honderich (ed.) Oxford:Oxford University Press. 1995.--></ref> This approach has been influential in the sciences, particularly in the fields of [[sociobiology]], [[computer science]], [[evolutionary psychology]] and the various [[neuroscience]]s.<ref name="PsyBio">Pinel, J. ''Psychobiology'', (1990) Prentice Hall, Inc. ISBN 8815071741</ref><ref name="LeDoux">LeDoux, J. (2002) ''The Synaptic Self: How Our Brains Become Who We Are'', New York:Viking Penguin. ISBN 8870787958</ref><ref name=RussNor">Russell, S. and Norvig, P. ''Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach'', New Jersey:Prentice Hall. ISBN 0131038052</ref><ref name="DawkRich">Dawkins, R. ''The Selfish Gene'' (1976) Oxford:Oxford University Press. ISBN</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| − | The mind-body problem can be introduced more fully with the following example. Suppose John decides to walk across the room, whereupon he does in fact walk across the room. John's decision is a mental event and his walking across the room is a physical event. In addition, there is ''another'' physical event involved, namely, something occurs in John's brain that tells John's legs to start walking. This brain event is closely connected with John's decision; the brain event happens at about the same time, or right after, John decides to walk across the room. One might ask: how is it possible that a decision, a ''mental'' event, results in something ''physical'' happening in John's brain? If it is claimed that the mental and the physical are completely different, then how can one have any causal impact on the other? How can a mere mental event, a decision, actually cause neurons in one's brain to start firing? |

||

| + | Dualism is the idea that the mental and the physical are two completely different kinds of things. In more technical language, dualism holds that [[mind]] and [[body]] are distinct types of substance, where a substance is a type of thing or entity that can exist on its own, independently of other types of entities. In traditional ontology, substances are the ultimate bearers of properties. They are definable by their essential properties, those properties that make them to be the kind of thing that they are. The essential properties of mind would thus be the mental properties, whichever they are (e.g., conscious states, states that are inherently representational, or however the mental is defined). Body or matter would have as its essential properties the physical or material properties, whichever they are (e.g., spatial extension, mass, force, or however the physical or the material is defined). |

||

| − | A different philosophical view describes the situation thus: John's decision is ''itself'' a physical event. When John decides to take a walk across the room, a group of [[neuron]]s fire in his brain. He is not aware of those neurons; but the firing of those neurons is itself just the same as his decision. There isn't any more to the decision than that physical event. In this view there's no trouble thinking about how a mental event can have a physical effect; mental events are themselves physical. Ultimately, everything is physical. |

||

| + | Within Western Philosophy, the first major proponent of dualism was [[Plato]]. Plato put forward a theory that the most basic realities are Forms or abstract types, a theory known as [[Platonic idealism]]. But he also held that mind and body are distinct. Subsequent Platonists, such as Augustine of Hippo, adopted this position. |

||

| − | To many it may sound strange to say that a mental process is no more than a special kind of physical process. Many believe the mind is more spiritual, ethereal, and is simply not the sort of thing that can be physical. Still, there are other reasons for rejecting this reduction of the mental to the physical. |

||

| ⚫ | The most famous adherent of dualism was [[René Descartes|Descartes]], who proposed a type of dualism that has come to be known as ''[[Cartesian dualism]]'' or ''Interaction Dualism''. Cartesian dualism is the idea that mind and body are two fundamentally different types of things, but that they can interact in the brain. Physical events can cause mental events—for example, the physical act of hitting your hand with a hammer can cause nerve processes that affect the mind and produce the experience of pain. Conversely, mental events can cause physical events—for example, the mental decision to speak can cause nerve processes that make your tongue move. |

||

| − | In the past, some philosophers have believed instead that the [[reduction]] goes the other way, that the body should be explained in terms of mental events. In this way, the physical is reduced to the mental. In this view, when John walks across the room, really that was only happening in John's mind and perhaps also in each of our minds individually at the same time. There is, in this view, nothing more to John's walking across the room than our having the thought, or the perception, that it happens. This view would also solve the problem of how the mental can affect the physical. Since physical events are themselves nothing more than a special kind of mental event, then of course there is no trouble about how a decision, which is obviously a mental event, can result in our bodies moving, which is also a mental event, although less obviously so. |

||

| + | A dualistic philosophy, by definition, recognizes the existence of both mind and body. In Descartes' philosophy, the body plays an important role in psychological functions. This is most clearly seen in his theory of the passions, which is a "body-first" theory. That means that bodily mechanisms condition which passion or emotion a human being will feel in given circumstances. These bodily mechanisms direct the person's response to the situation: flight from a frightful animal, embrace of a friendly companion. The mind's role is then to continue or to redirect the response that has begun with the body.<ref>Gary Hatfield, "The ''Passions of the Soul'' and Descartes's machine psychology," ''Studies in History and Philosophy of Science'' 38 (2007), 1–35.</ref> |

||

| − | The three above-described views about the relationship between the mental and the physical have names: |

||

| + | In the twentieth century, some interpreters concluded that Descartes' philosophy leads one to consider the corporeal as of little value<ref name="Young">''[http://human-nature.com/rmyoung/papers/pap102h.html The mind-body problem]'' by Robert M. Young</ref> and trivial. A rejection of this type of view of the mind-body relation is found in French [[Structuralism]], and is a position that generally characterized post-war French philosophy.<ref>Turner 1996, p. 76</ref> |

||

| − | * ''[[Dualism (philosophy of mind)|Dualism]]'' is the view that mental events and physical events are totally different kinds of events. |

||

| ⚫ | ''[[Epiphenomenalism]]'' can be another type of dualism, if the epiphenomenalist holds that mind and body are two fundamentally different types of things. This substance epiphenomenalism agrees with Cartesian dualism in saying that physical causes can give rise to mental events-- the physical act of hitting your hand with a hammer will create the mental experiene of pain. Unlike Cartesian dualism, epiphenomenalism argues that mental events cannot under any circumstances give rise to physical effects. So, if my hand touches fire, the physical heat can cause the mental sensation of pain, and my hand instantly recoils. It might appear that the mental experience of pain caused the physical event of the hand pulling back. According to Epiphenomenalism, this is an illusion—in reality, the physical heat directly caused the recoiling of the hand through nerve processes, and these same processes also cause the sensation of the pain. The mental events are caused by physical events, but they cannot themselves have any affect on matter. |

||

| − | * ''[[Materialism]]'', or ''[[physicalism]]'', is the view that mental events are nothing more than a special kind of physical event. |

||

| ⚫ | ''Parallelism'', as a form of dualism, argues that mental and physical events occur in separate domains and constitute two fundamentally different types of things that can never interact in any way. This view admits that physical events appear to cause mental effects (hitting your hand with a hammer appears to cause pain) and that mental events appear to cause physical effects (deciding to speak appears to cause your tongue to move). Parallelism, however, holds that this correspondence between the mental world and the physical world is simply a correlation, not the result of causation. The nerve processes caused by the hammer form a close looped that cause your hand to draw back. A separate chain of mental events run in parallel; you see the hammer hit your hand, and you subsequently feel pain. In this view, the mental world and the physical world are parallel, but separate, never directly interacting. |

||

| − | * ''[[Phenomenalism]]'', or ''[[subjective idealism]]'', is the view that physical events are nothing more than a special kind of mental event. |

||

| + | ===Physicalism=== |

||

| − | Materialism and Phenomenalism are two opposite forms of monism since they both assume that only a kind of substance (respectively, matter or mind) exists. |

||

| ⚫ | [[Physicalism]] is the idea that everything in the universe can be explained by and consists of physical entities such as matter and energy. The most basic form of physicalism is the ''identity theory'', according to which all mental states are identical with physical states in the brain. In this view, while mental entities (such as thoughts and feelings) might at first appear to be a completely novel type of thing, in reality, the mental is completely reducible to the physical. All your thoughts and experiences are simply physical processes in your brain. Physicalism argues that ultimately the physical world and its laws explain the behavior of everything in the universe, including the behavior of humans.<ref>Jaegwon Kim, "Problems in the Philosophy of Mind," in ''Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Ted Honderich (ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.</ref> Physicalism is sometimes called [[materialism]]. |

||

| − | The mind-body problem, to put it as generically and broadly as possible, is this question: "What is the basic relationship between the mental and the physical?" For the sake of simplicity, we can state the problem in terms of mental and physical events. It could just as well be put in terms of processes, or of [[consciousness]]. So the problem restated is: "What is the basic relationship between mental events and physical events?" |

||

| + | According to physicalism, when you hit your hand with the hammer, nerve processes proceed to the brain and cause a central brain state. This central brain state does not cause you to feel pain, rather it ''is'' your pain. Somehow, the pattern of activation of neurons in your brain ''just is'' the feeling of pain. For every type of mental state, there should be a corresponding physical state to which it reduces. Thus, your decision to speak is also simply another pattern of activation in the brain. This neural activity, which itself just is the decision, then causes your tongue to move. |

||

| ⚫ | There are |

||

| + | The entire sequence of causation could be described solely in physical terms. But it may also be described using the mental or psycyhological terms that name states and processes that are identical to physical states and processes. Reductive physicalism does not eliminate the mental; rather, it reduces the mental to the physical. Another form of materialism, call "[[materialism|eliminative materialism]]," seeks to eliminate, rather than to reduce, mental predicates. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| − | Dualism is the idea that the mental and the physical are two completely different kinds of things. |

||

| + | Well-known identity theorists of the twentieth-century included the British philosopher U. T. Place and the Australian philosopher J. J. C. Smart. |

||

| − | Within Western Philosophy, the first major proponent of Dualism was [[Plato]], who put forward a concept that has come to be known as [[Platonic idealism]]. Platonic idealism is the theory that the substantive reality around us is only a reflection of a higher truth. That truth, Plato argues, is the abstraction. A particular tree, with a branch or two missing, possibly alive, possibly dead, and initials of two lovers carved into its bark, is distinct from the form of Tree-ness. A Tree is the ideal that each of us holds that allows us to identify the imperfect reflections of trees all around us. |

||

| + | ===Idealism=== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Idealism is the view that physical objects, properties, events (whatever is described as physical) are reducible to mental objects, properties, events. Ultimately, only mental objects exist. According to idealism, the material world is not unlike a dream. When you have a vivid dream, you find yourself in a dream world that appears to be composed of material objects. In reality, however, everything in your dreamworld is a creation of your dream. If you dream you are riding a bicycle, the bicycle certainly feels real. In reality, however, the bicycle does not have an independent existence outside of your own mind. When you awaken, the bicycle might cease to be. Idealism holds that the entire "real world" of our waking lives is fundamentally a mental creation. Only minds and their experiences exist. |

||

| ⚫ | [[Epiphenomenalism]] |

||

| + | The best known idealist is the eighteenth-century Irish philosopher George Berkeley, Bishop of Cloyne. Berkeley argued that the notion of material substance is incoherent. As a consequence of his argument, he concluded that only minds and their internal states, or "ideas," exist. He granted the existence of human minds and of a divine mind, or God. According to Berkeley, all the ideas in the human mind are produced by God. Sensory ideas are produced in the form of a coherent view of what appears to be a physical reality. But, he maintained, these sensory ideas in fact have only mental existence. All the shapes and colors that we experience exist only in the mind. Berkeley is responsible for the philosophical chestnut, "if a tree falls in the forest and no one is there, does it produce a sound?" He answered that it does, because the infinite mind, God, is aware of the tree and its sound. |

||

| ⚫ | ''Parallelism'' |

||

| − | === |

+ | ===Other monisms=== |

| + | Physicalism and idealism are substance monisms. They posit only one type of substance in the world, whether physical or mental. Another type of monism is ''dual-aspect monism''. This position holds that there is only one type of substance, which is itself neither physical nor mental. Rather, the physical and the mental are two aspects of this substance, or two ways in which the one substance manifests itself. When you hit your hand with the hammer, the damage to your skin, muscles, and bones is the physical aspect, and the pain is the mental aspect. The damage doesn't cause the pain. Rather, the damage and the pain are two aspects of a single underlying state of the one substance. This view was made prominent by the [[17th century]] Dutch philosopher [[Benedictus de Spinoza|Benedict de Spinoza]]. |

||

| ⚫ | [[Physicalism]] is the idea that everything in the universe can be explained by physical entities such as matter and energy. In this view, while mental entities (such as thoughts and feelings) might at first appear to be a completely novel type of thing, in reality, the mental is completely |

||

| + | Yet a further type of monism is called ''[[neutral monism]]''. This view denies that the mental and the physical are two fundamentally different things. Rather, neutral monism claims the universe consists of only one kind of stuff, in the form of neutral elements that are in themselves neither mental nor physical. These neutral elements are like sensory experiences: they might have the properties of color and shape, just as we experience those properties. But these shaped and colored elements do not exist in a mind (considered as a substantial entity, whether dualistically or physicalistically); they exist on their own. |

||

| − | In colloquial speech, Physicalism is sometimes simply called [[Materialism]]. Technicially, however, [[Materialism]] is a very specific subtype of [[Physicalism]] which claims everything in the universe is matter. So Physicalism accepts non-material physical entities such as energy, space, and time; technically speaking, Materialism does not accept the independent existence of anything but matter. |

||

| + | Some subset of these elements form individual minds: the subset of just the experiences that you have for the day, which are accordingly just so many neutral elements that follow upon one another, is your mind as it exists for that day. If instead you described the elements that would consistute the sensory experience of rock by the path, then those elements constitute that rock. They do so even if no one observes the rock. The neutral elements exist, and our minds are constituted by some subset of them, and that subset can also be seen to constitute a set of empirical observations of the objects in the world. All of this, however, is just a matter of grouping the neutral elements in one way or another, according to a physical or a psychological (mental) perspective. |

||

| − | ===Phenomenalism=== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Another philosophical viewpoint, known as [[New Mysterianism]], holds that the solution to the mind-body problem is unsolvable, particularly by humans. Just as a mouse could never understand human speech, perhaps humans simply lack the capacity to understand the solution to the mind-body problem.<ref>Colin McGinn, "Can the Mind-Body Problem Be Solved," ''Mind'', n.s. 98 (1989), 349–366.</ref> |

||

| − | ===Neutral monism=== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| − | A fourth position is called [[neutral monism]]. This view denies that the Mental and the Physical are two fundamentally different things. Rather, Neutral monism claims the universe consists of only one kind of primal stuff, which in itself is neither mental nor physical, but is capable of both mental and physical aspects or attributes. This view was introduced by the [[17th century]] Dutch philosopher [[Baruch Spinoza]]. |

||

| + | Throughout the history of modern psychology, many theorists have been interested in the mind-brain relation, no matter which metaphysical position they adopted (dualism or one of the monisms). Descartes held that there are lawful relations between brain states at the pineal gland and sensations or felt emotions. During the nineteenth-century, [[Gustav Fechner]] developed psychophysics as a way to study the relations between the mental and the physical. He is best known for his "outer psychophysics," which seeks to describe the relation between external physical stimuli, such as lights of various wavelengths, and mental states, such as sensations of one or another color. He was, however, perhaps even more interested in "inner psychophysics," which would establish a relation between brain states and sensations.<ref>Eckart Scheerer, "The unknown Fechner," ''Psychological Research'' 49 (1987), 197–202.</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | During the latter part of the nineteenth century, the new experimental psychologists often held that the empirical questions of scientific psychology should be posed in a way that did not presuppose any one of the metaphysical solutions to the mind–body problem. They thus sought to study the mind–brain relation, without seeking to establish scientifically whether, say, materialism or neutral monism was the better metaphysical theory. William James, who as a philosopher endorsed neutral monism, advised the psychologist to take the methodological attitude of "empirical parallelism."<ref>William James, ''Principles of Psychology'', 2 vols., New York: Holt, 1890, 1: 182.</ref> By this he meant that the psychologist should simply seek to chart the empirical correlations between mental states and brain processes. James viewed this position as a "provisional halting place,"<ref>Ibid.</ref> pending further philosophical progress on the metaphysics of the mind–body problem. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | During the twentieth century, psychologists adopted various outlooks on the mind–body problem. Behaviorists such as [[John B. Watson]], [[Clark Hull]], and [[B. F. Skinner]], were eliminativists. They wished to do away with all mentalistic talk in scientific psychology. Other behaviorists, such as [[Edward C. Tolman]], allowed for mentalistic talk in psychology, including talk of mental representations, goals, and purposes, as long as such notions were clearly tied to observable behavior. Tolman did not propose a solution to the mind–body problem, but neither did he follow the other behaviorists in ignoring mental factors. |

||

| − | ==Theological perspectives== |

||

| + | The Gestalt psychologists, [[Wolfgang Kohler]], [[Kurt Koffka]], and [[Max Wertheimer]], proposed their own account of the mind–body relation, in the form of psychophysical isomorphism. [[Gestalt psychology]] is noted for its emphasis on organized wholes within perceptual and cognitive experience. An example of such organized structure is the figure/ground relation as in the Rubin vase at the right of the image, or multi-stable structure, such as the Necker cube on the left.[[Image:Multistability.jpg|thumb|200px|right|Necker cube and Rubin vase. The Necker cube shifts between two differently oriented cubes in three-dimensions. The Rubin vase shifts between a vase and opposed faces.]] |

||

| − | Many [[Atheism|atheists]] endorse [[physicalism]] (or [[materialism]]). To most atheists the physical world is all that is real. Souls, spirits, and minds either are completely mythical, or else they are explainable by physical events. Some atheists, such as [[Colin McGinn]], reject physicalism but argue that ultimately we cannot know or understand the correct alternative answer. |

||

| + | According to Gestalt psychophysical isomorphism, the organization in perceptual experience is directly correlated with organized field structures in the brain. When the Necker cube shifts its structure, the field structures undergo a parallel shift. The Gestaltists did not hold that the brain process was literally shaped as a cube, but they did posit a strong spatial isomorphism. The brain process should have structures that correspond to the faces of the cube, and these structures should alter during the switching of the experienced Necker cube. Similarly for the faces and vase. The Gestaltists did not claim to solve the mind–body problem. Rather, they were proposing an explanatory relation between brain structures and correlated mental events (perceptual experiences). They did not ultimately decide whether the metaphysical relation was reductive or fit another theory, such as dual-aspect monism. |

||

| − | Mainstream [[Christianity]] has generally adhered to [[Cartesian dualism]]. In their view, both the material world and the spiritual world are real, and the two worlds can interact. Each person has an immaterial soul which inhabits a physical body and will survive the death of the physical body. Souls can affect the physical world (through free will) and God can affect the physical world (through miracles). Jesus was an immortal spirit that took on physical form (the "Word made flesh", see [[Logos]]). |

||

| + | Throughout the twentieth century, some perceptual psychologists retained an interest in establishing the neural correlates of psychological processes. This sort of empirical interest was especially strong among perceptual psychologists working on color perception. Leo Hurvich and Dorothea Jameson, using phenomenally based methods of psychological research, revived the opponent-process theory of color perception.<ref>Leo M. Hurvich and Dorothea Jameson, "An opponent-process theory of color vision," ''Psychological Review'' 64 (1957), 384–404.</ref> Other experimentalists, using single-cell recording techniques, then found evidence for opponent neural responses in the retina<ref>Gunnar Svaetichin, "Spectral response curves from single cones," ''Acta Physiologica Scandinavica'' 39 (supp. 134, 1956), 17–46.</ref> and in the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN).<ref>Russell L. DeValois, I. Abramov, and Gerald H. Jacobs, "Analysis of response patterns of LGN cells," ''Journal of the Optical Society of America'' 56 (1966), 966–77.</ref> |

||

| − | [[Occasionalism]] is a theological form of ''parallelism'' -- it argues that mental events can never cause physical effects, and that physical events can never cause mental effects. Rather, Occasionalism holds that all events are ultimately caused directly by God. For a variety of reasons, Occasionalism is generally not subscribed to by most mainstream religions. See [[Occasionalism]] for a wider discussion. |

||

| + | During the 1980s, the perceptual psychologists Davida Teller and Ed Pugh attended to the formal structure of the problem of establishing psychoneural relations. They encouraged physiological psychologists to formulate explicit psychoneural linking propositions, that is, propositions relating dimensions of perceptual experience to specific processes and structures in the brain.<ref>Davida Y. Teller and Edward N. Pugh, "Linking propositions in color vision," in ''Colour Vision: Physiology and Psychophysics'', John D. Mollon and Lindsey T. Sharpe (eds.), London: Academic Press, 1983, 577–89.</ref> |

||

| − | [[Idealism]] also has its theological versions: Several modern religious movements and texts, for example the organisations within the [[New Thought Movement]] (especially the [[Unity Church]]) and the book, [[A Course in Miracles]], may be said to have a particularly [[Idealism]]-inspired orientation. The theology of [[Christian Science]] is explicitly idealist. |

||

| + | In the neuroscience community outside of physiological psychology, for some decades prior to the 1990s few neuroscientists spoke of consciousness and even fewer would be bold enough to try to approach the topic scientifically. During the 1990s, a major shift occurred in this wider neuroscience community: the topic of consciousness and its relation to brain function was again accepted as a respectable topic that many neuroscientists took seriously. Because of the legacy of behaviorism, which was strong and long-lasting in neuroscience, consciousness had not been considered a topic that was amenable to the methods of science. The change in the neuroscientific community of the 1990s is largely due to outspoken scientists such as [[Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine|Nobel-laureates]] [[Francis Crick]] and [[Gerald Edelman]], as well as the influence of philosophers such as [[David Chalmers]], [[Daniel Dennett]], and [[Fred Dretske]]. |

||

| − | Some religions view the mental world as superior, while regarding the physical world as inherently flawed, inferior, or painful. Theologies with this view include [[Gnostic Christianity]], [[Christian Science]], and subsets of [[Hinduism]] and [[Buddhism]]. |

||

| ⚫ | Most [[neuroscience|neuroscientists]] believe in the identity of mind and brain, the position of materialism and physicalism. However, some neuroscientists may instead embrace dual-aspect monism, because they do not accept that in postulating an identity between mind and brain (or more specifically, particular types of neuronal interactions) they are implying that mental events are "nothing more" than physical events. Such a neuroscientist would accept that physical events and mental events are different aspects of a more fundamental mental–physical substratum which can be perceived as both mental and physical, depending on perspective. Working neuroscientists do not often address their metaphysical convictions in print, so it may be difficult to know which of these positions they hold (if either), or even whether they distinguish between them. |

||

| − | ==Scientific perspectives== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Most [[neuroscience|neuroscientists]] believe in the identity of mind and brain, |

||

| + | Neuroscience has not established an NCC. Future research will reveal how far it can go in discovering such correlates. However, discovering such correlates will not solve the mind–body problem as it is normally posed. To see this, consider that individual theorists with widely differing theoretical perspectives all would have liked to learn the exact empirical correlations between brain processes and conscious states. These theorists include Descartes, Fechner, and the Gestalt psychologists, who had differing outlooks on the mind–brain relation. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | To solve the mind–body problem it will not be enough to show that perception or consciousness is correlated with neural processes. Rather, a theoretical solution would need ''to explain'' the experienced aspects of perception and consciousness by showing how such aspects can be derived from the activity of neurons (or whatever aspects of brain activity are relevant). No one has proved that such an understanding cannot be achieved (contrary to the dire predictions of the new mysterians). On the other hand, no one really knows what such an understanding would look like. That's why the mind–body problem remains today in the category of unsolved problems. Work toward a solution may be facilitated if theorists are explicit about their assumptions and goals in studying the relations between the mental and the physical. |

||

| − | A major shift in the neurosciences occurred in the 1990s: the topic of consciousness and its relation to brain function has become a respectable topic that many neuroscientists take seriously. Prior to the 1990s, few neuroscientists spoke of consciousness, and even fewer would be bold enough to try to approach the topic scientifically. Consciousness was not considered a topic that was amenable to the methods of science. The tide change in the neuroscientific community of the 1990s is largely due to outspoken scientists such as [[Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine|Nobel-laureate]] [[Francis Crick]], and philosophers such as [[David Chalmers]]. While neuroscience has not yet solved the mind-brain problem in terms of coming up with an NCC, to many in the field, the next decade looks promising. Future research may soon reveal how far science can go in addressing and solving the question of the mind-brain problem. |

||

| − | |||

| − | A research team at [[Caltech]] discovered in 2005 that individual brain cells can fire in response to visual stimuli of individual people or places, which conflicted with previous conjectures that visual recognition was an [[emergent phenomenon]] of large networks of neurons. This development gives weight to [[Roger Penrose]]'s suggestion in his 1994 book ''[[Shadows of the Mind: A Search for the Missing Science of Consciousness]]'' that the activity giving rise to consciousness occurs inside neurons at the scale where [[quantum]] phenomena transitions to [[classical physics]]. |

||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

| + | {{col-begin}} |

||

| − | |||

| + | {{col-break}} |

||

* [[consciousness]] |

* [[consciousness]] |

||

* [[Daniel Dennett]] |

* [[Daniel Dennett]] |

||

| Line 88: | Line 115: | ||

* [[functionalism (philosophy of mind)]] |

* [[functionalism (philosophy of mind)]] |

||

* [[materialism]] |

* [[materialism]] |

||

| − | * [[Mental body]] |

||

* [[Mind]] |

* [[Mind]] |

||

* [[monism]] |

* [[monism]] |

||

* [[Odic force]] |

* [[Odic force]] |

||

| + | {{col-break}} |

||

* [[Thomas Nagel]] |

* [[Thomas Nagel]] |

||

* [[panpsychism]] |

* [[panpsychism]] |

||

| Line 101: | Line 128: | ||

* [[supervenience]] |

* [[supervenience]] |

||

* [[Theory of mind]] |

* [[Theory of mind]] |

||

| + | {{col-end}} |

||

| + | |||

| + | ==Notes and citations== |

||

| + | <div class="references-small" style="-moz-column-count:2; column-count:2;"> |

||

| + | <references/> |

||

| + | </div> |

||

| + | |||

| + | == Bibliography == |

||

| + | |||

| + | * Descartes, René (1664). ''L’Homme de René Descartes: et vn traitté de la formation du foetus''. Paris: Le Gras. |

||

| + | |||

| + | * Descartes, René (1989). ''Passions of the Soul'', trans. Stephen Voss. Indianapolis: Hackett. Original French version published in 1649. |

||

| + | |||

| + | * Edelman, Gerald M. (2004). ''Wider Than the Sky: The Phenomenal Gift of Consciousness''. New Haven: Yale University Press. |

||

| + | |||

| + | * Kim, Jaegwon (2005). ''Physicalism, or Something Near Enough''. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. |

||

| + | |||

| + | * Seager, William (1999). ''Theories of Consciousness: An Introduction and Assessment''. London: Routledge. |

||

| + | |||

| + | * Shapiro, Lawrence A. (2004). ''The Mind Incarnate''. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. |

||

| + | |||

| + | * Turner, Bryan S. (1996). ''[http://books.google.com/books?id=K_8WxOqOWtMCThe Body and Society: Exploration in social theory]'' |

||

| + | |||

| + | * Velmans, Max, and Susan Schneider (eds.) (2007). ''Blackwell Companion to Consciousness''. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell. |

||

| + | |||

| + | * Zelazo, Philip David, Morris Moscovitch, and Evan Thompson (eds.) (2007). ''Cambridge Handbook of Consciousness''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. |

||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

| + | * [http://serendip.brynmawr.edu/Mind/ MIND AND BODY: RENÉ DESCARTES TO WILLIAM JAMES], Robert H. Wozniak, Bryn Mawr College – introductory historical overview. |

||

* [http://www.foothill.net/~jerryi/INTRODUCTION_PDF_PAGELINK.html The Mind-Brain Problem] - an introduction for beginners (article in pdf format). |

* [http://www.foothill.net/~jerryi/INTRODUCTION_PDF_PAGELINK.html The Mind-Brain Problem] - an introduction for beginners (article in pdf format). |

||

* [http://sci-con.org/ Sci-Con.org] - Science and Consciousness Review, a site maintained by such notables as Bernard Baars, among others. |

* [http://sci-con.org/ Sci-Con.org] - Science and Consciousness Review, a site maintained by such notables as Bernard Baars, among others. |

||

* [http://www.u.arizona.edu/~chalmers/ David Chalmers' Homepage] - a large collection of essays from one of the leading philosophers in the consciousness field. |

* [http://www.u.arizona.edu/~chalmers/ David Chalmers' Homepage] - a large collection of essays from one of the leading philosophers in the consciousness field. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

* [http://philosophy.uwaterloo.ca/MindDict/ Philosophy of the Mind] - an index of the mind-body problem. |

* [http://philosophy.uwaterloo.ca/MindDict/ Philosophy of the Mind] - an index of the mind-body problem. |

||

* [http://cogprints.org/1623/00/bookrev.htm Explaining the Mind: Problems, Problems] |

* [http://cogprints.org/1623/00/bookrev.htm Explaining the Mind: Problems, Problems] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[de:Leib-Seele-Problem]] |

||

| − | [[fr:Problème corps-esprit]] |

||

| − | [[he:הבעיה הפסיכופיזית]] |

||

| − | [[ja:心身問題の哲学]] |

||

[[Category:Consciousness studies]] |

[[Category:Consciousness studies]] |

||

[[Category:Philosophy of mind]] |

[[Category:Philosophy of mind]] |

||

| − | |||

| − | {{enWP|The_mind-body_problem}} |

||

Revision as of 22:58, 16 April 2014

Assessment |

Biopsychology |

Comparative |

Cognitive |

Developmental |

Language |

Individual differences |

Personality |

Philosophy |

Social |

Methods |

Statistics |

Clinical |

Educational |

Industrial |

Professional items |

World psychology |

Philosophy Index: Aesthetics · Epistemology · Ethics · Logic · Metaphysics · Consciousness · Philosophy of Language · Philosophy of Mind · Philosophy of Science · Social and Political philosophy · Philosophies · Philosophers · List of lists

René Descartes' illustration of brain anatomy and physiology. Inputs are passed on by the sensory organs to the pineal gland in the brain and from there to the motor nerves. At the pineal gland, the nerve processes affect the mind, an immaterial spirit, in accordance with Descartes' mind/body dualism. The mind can also affect the pineal gland, thereby directing the processes of the motor nerves. From Descartes (1664).

The mind-body problem can be stated as, "What is the basic relationship between the mental and the physical?" For the sake of simplicity, we can state the problem in terms of mental and physical events: "What is the basic relationship between mental events and physical events?" It could also be stated in terms of the relation between mental and physical states and/or processes, or between the brain and consciousness.

There are three basic metaphysical positions: mental and physical events are totally different, and cannot be reduced to each other (dualism); mental events are to be reduced to physical events (materialism); and physical events are to be reduced to mental events (idealism). To put it in terms of what exists "ultimately," we could say that according to dualism, both mental and physical events exist ultimately; according to materialism, only physical events exist ultimately; and according to idealism, only mental events exist ultimately. Materialism and idealism are both varieties of monism, and of monism there are two further varieties, namely dual-aspect monism and neutral monism.

The absence of an empirically identifiable meeting point between the non-physical mind and the physically extended body has proven problematic to dualism and many modern philosophers of mind maintain that the mind is not something separate from the body.[1] This approach has been influential in the sciences, particularly in the fields of sociobiology, computer science, evolutionary psychology and the various neurosciences.[2][3][4][5]

Dualism

Dualism is the idea that the mental and the physical are two completely different kinds of things. In more technical language, dualism holds that mind and body are distinct types of substance, where a substance is a type of thing or entity that can exist on its own, independently of other types of entities. In traditional ontology, substances are the ultimate bearers of properties. They are definable by their essential properties, those properties that make them to be the kind of thing that they are. The essential properties of mind would thus be the mental properties, whichever they are (e.g., conscious states, states that are inherently representational, or however the mental is defined). Body or matter would have as its essential properties the physical or material properties, whichever they are (e.g., spatial extension, mass, force, or however the physical or the material is defined).

Within Western Philosophy, the first major proponent of dualism was Plato. Plato put forward a theory that the most basic realities are Forms or abstract types, a theory known as Platonic idealism. But he also held that mind and body are distinct. Subsequent Platonists, such as Augustine of Hippo, adopted this position.

The most famous adherent of dualism was Descartes, who proposed a type of dualism that has come to be known as Cartesian dualism or Interaction Dualism. Cartesian dualism is the idea that mind and body are two fundamentally different types of things, but that they can interact in the brain. Physical events can cause mental events—for example, the physical act of hitting your hand with a hammer can cause nerve processes that affect the mind and produce the experience of pain. Conversely, mental events can cause physical events—for example, the mental decision to speak can cause nerve processes that make your tongue move.

A dualistic philosophy, by definition, recognizes the existence of both mind and body. In Descartes' philosophy, the body plays an important role in psychological functions. This is most clearly seen in his theory of the passions, which is a "body-first" theory. That means that bodily mechanisms condition which passion or emotion a human being will feel in given circumstances. These bodily mechanisms direct the person's response to the situation: flight from a frightful animal, embrace of a friendly companion. The mind's role is then to continue or to redirect the response that has begun with the body.[6]

In the twentieth century, some interpreters concluded that Descartes' philosophy leads one to consider the corporeal as of little value[7] and trivial. A rejection of this type of view of the mind-body relation is found in French Structuralism, and is a position that generally characterized post-war French philosophy.[8]

Epiphenomenalism can be another type of dualism, if the epiphenomenalist holds that mind and body are two fundamentally different types of things. This substance epiphenomenalism agrees with Cartesian dualism in saying that physical causes can give rise to mental events-- the physical act of hitting your hand with a hammer will create the mental experiene of pain. Unlike Cartesian dualism, epiphenomenalism argues that mental events cannot under any circumstances give rise to physical effects. So, if my hand touches fire, the physical heat can cause the mental sensation of pain, and my hand instantly recoils. It might appear that the mental experience of pain caused the physical event of the hand pulling back. According to Epiphenomenalism, this is an illusion—in reality, the physical heat directly caused the recoiling of the hand through nerve processes, and these same processes also cause the sensation of the pain. The mental events are caused by physical events, but they cannot themselves have any affect on matter.

Parallelism, as a form of dualism, argues that mental and physical events occur in separate domains and constitute two fundamentally different types of things that can never interact in any way. This view admits that physical events appear to cause mental effects (hitting your hand with a hammer appears to cause pain) and that mental events appear to cause physical effects (deciding to speak appears to cause your tongue to move). Parallelism, however, holds that this correspondence between the mental world and the physical world is simply a correlation, not the result of causation. The nerve processes caused by the hammer form a close looped that cause your hand to draw back. A separate chain of mental events run in parallel; you see the hammer hit your hand, and you subsequently feel pain. In this view, the mental world and the physical world are parallel, but separate, never directly interacting.

Physicalism

Physicalism is the idea that everything in the universe can be explained by and consists of physical entities such as matter and energy. The most basic form of physicalism is the identity theory, according to which all mental states are identical with physical states in the brain. In this view, while mental entities (such as thoughts and feelings) might at first appear to be a completely novel type of thing, in reality, the mental is completely reducible to the physical. All your thoughts and experiences are simply physical processes in your brain. Physicalism argues that ultimately the physical world and its laws explain the behavior of everything in the universe, including the behavior of humans.[9] Physicalism is sometimes called materialism.

According to physicalism, when you hit your hand with the hammer, nerve processes proceed to the brain and cause a central brain state. This central brain state does not cause you to feel pain, rather it is your pain. Somehow, the pattern of activation of neurons in your brain just is the feeling of pain. For every type of mental state, there should be a corresponding physical state to which it reduces. Thus, your decision to speak is also simply another pattern of activation in the brain. This neural activity, which itself just is the decision, then causes your tongue to move.

The entire sequence of causation could be described solely in physical terms. But it may also be described using the mental or psycyhological terms that name states and processes that are identical to physical states and processes. Reductive physicalism does not eliminate the mental; rather, it reduces the mental to the physical. Another form of materialism, call "eliminative materialism," seeks to eliminate, rather than to reduce, mental predicates.

Well-known identity theorists of the twentieth-century included the British philosopher U. T. Place and the Australian philosopher J. J. C. Smart.

Idealism

Idealism is the view that physical objects, properties, events (whatever is described as physical) are reducible to mental objects, properties, events. Ultimately, only mental objects exist. According to idealism, the material world is not unlike a dream. When you have a vivid dream, you find yourself in a dream world that appears to be composed of material objects. In reality, however, everything in your dreamworld is a creation of your dream. If you dream you are riding a bicycle, the bicycle certainly feels real. In reality, however, the bicycle does not have an independent existence outside of your own mind. When you awaken, the bicycle might cease to be. Idealism holds that the entire "real world" of our waking lives is fundamentally a mental creation. Only minds and their experiences exist.

The best known idealist is the eighteenth-century Irish philosopher George Berkeley, Bishop of Cloyne. Berkeley argued that the notion of material substance is incoherent. As a consequence of his argument, he concluded that only minds and their internal states, or "ideas," exist. He granted the existence of human minds and of a divine mind, or God. According to Berkeley, all the ideas in the human mind are produced by God. Sensory ideas are produced in the form of a coherent view of what appears to be a physical reality. But, he maintained, these sensory ideas in fact have only mental existence. All the shapes and colors that we experience exist only in the mind. Berkeley is responsible for the philosophical chestnut, "if a tree falls in the forest and no one is there, does it produce a sound?" He answered that it does, because the infinite mind, God, is aware of the tree and its sound.

Other monisms

Physicalism and idealism are substance monisms. They posit only one type of substance in the world, whether physical or mental. Another type of monism is dual-aspect monism. This position holds that there is only one type of substance, which is itself neither physical nor mental. Rather, the physical and the mental are two aspects of this substance, or two ways in which the one substance manifests itself. When you hit your hand with the hammer, the damage to your skin, muscles, and bones is the physical aspect, and the pain is the mental aspect. The damage doesn't cause the pain. Rather, the damage and the pain are two aspects of a single underlying state of the one substance. This view was made prominent by the 17th century Dutch philosopher Benedict de Spinoza.

Yet a further type of monism is called neutral monism. This view denies that the mental and the physical are two fundamentally different things. Rather, neutral monism claims the universe consists of only one kind of stuff, in the form of neutral elements that are in themselves neither mental nor physical. These neutral elements are like sensory experiences: they might have the properties of color and shape, just as we experience those properties. But these shaped and colored elements do not exist in a mind (considered as a substantial entity, whether dualistically or physicalistically); they exist on their own.

Some subset of these elements form individual minds: the subset of just the experiences that you have for the day, which are accordingly just so many neutral elements that follow upon one another, is your mind as it exists for that day. If instead you described the elements that would consistute the sensory experience of rock by the path, then those elements constitute that rock. They do so even if no one observes the rock. The neutral elements exist, and our minds are constituted by some subset of them, and that subset can also be seen to constitute a set of empirical observations of the objects in the world. All of this, however, is just a matter of grouping the neutral elements in one way or another, according to a physical or a psychological (mental) perspective.

New Mysterianism

Another philosophical viewpoint, known as New Mysterianism, holds that the solution to the mind-body problem is unsolvable, particularly by humans. Just as a mouse could never understand human speech, perhaps humans simply lack the capacity to understand the solution to the mind-body problem.[10]

Scientific perspectives

Throughout the history of modern psychology, many theorists have been interested in the mind-brain relation, no matter which metaphysical position they adopted (dualism or one of the monisms). Descartes held that there are lawful relations between brain states at the pineal gland and sensations or felt emotions. During the nineteenth-century, Gustav Fechner developed psychophysics as a way to study the relations between the mental and the physical. He is best known for his "outer psychophysics," which seeks to describe the relation between external physical stimuli, such as lights of various wavelengths, and mental states, such as sensations of one or another color. He was, however, perhaps even more interested in "inner psychophysics," which would establish a relation between brain states and sensations.[11]

During the latter part of the nineteenth century, the new experimental psychologists often held that the empirical questions of scientific psychology should be posed in a way that did not presuppose any one of the metaphysical solutions to the mind–body problem. They thus sought to study the mind–brain relation, without seeking to establish scientifically whether, say, materialism or neutral monism was the better metaphysical theory. William James, who as a philosopher endorsed neutral monism, advised the psychologist to take the methodological attitude of "empirical parallelism."[12] By this he meant that the psychologist should simply seek to chart the empirical correlations between mental states and brain processes. James viewed this position as a "provisional halting place,"[13] pending further philosophical progress on the metaphysics of the mind–body problem.

During the twentieth century, psychologists adopted various outlooks on the mind–body problem. Behaviorists such as John B. Watson, Clark Hull, and B. F. Skinner, were eliminativists. They wished to do away with all mentalistic talk in scientific psychology. Other behaviorists, such as Edward C. Tolman, allowed for mentalistic talk in psychology, including talk of mental representations, goals, and purposes, as long as such notions were clearly tied to observable behavior. Tolman did not propose a solution to the mind–body problem, but neither did he follow the other behaviorists in ignoring mental factors.

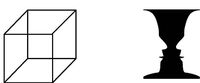

The Gestalt psychologists, Wolfgang Kohler, Kurt Koffka, and Max Wertheimer, proposed their own account of the mind–body relation, in the form of psychophysical isomorphism. Gestalt psychology is noted for its emphasis on organized wholes within perceptual and cognitive experience. An example of such organized structure is the figure/ground relation as in the Rubin vase at the right of the image, or multi-stable structure, such as the Necker cube on the left.

Necker cube and Rubin vase. The Necker cube shifts between two differently oriented cubes in three-dimensions. The Rubin vase shifts between a vase and opposed faces.

According to Gestalt psychophysical isomorphism, the organization in perceptual experience is directly correlated with organized field structures in the brain. When the Necker cube shifts its structure, the field structures undergo a parallel shift. The Gestaltists did not hold that the brain process was literally shaped as a cube, but they did posit a strong spatial isomorphism. The brain process should have structures that correspond to the faces of the cube, and these structures should alter during the switching of the experienced Necker cube. Similarly for the faces and vase. The Gestaltists did not claim to solve the mind–body problem. Rather, they were proposing an explanatory relation between brain structures and correlated mental events (perceptual experiences). They did not ultimately decide whether the metaphysical relation was reductive or fit another theory, such as dual-aspect monism.

Throughout the twentieth century, some perceptual psychologists retained an interest in establishing the neural correlates of psychological processes. This sort of empirical interest was especially strong among perceptual psychologists working on color perception. Leo Hurvich and Dorothea Jameson, using phenomenally based methods of psychological research, revived the opponent-process theory of color perception.[14] Other experimentalists, using single-cell recording techniques, then found evidence for opponent neural responses in the retina[15] and in the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN).[16]

During the 1980s, the perceptual psychologists Davida Teller and Ed Pugh attended to the formal structure of the problem of establishing psychoneural relations. They encouraged physiological psychologists to formulate explicit psychoneural linking propositions, that is, propositions relating dimensions of perceptual experience to specific processes and structures in the brain.[17]

In the neuroscience community outside of physiological psychology, for some decades prior to the 1990s few neuroscientists spoke of consciousness and even fewer would be bold enough to try to approach the topic scientifically. During the 1990s, a major shift occurred in this wider neuroscience community: the topic of consciousness and its relation to brain function was again accepted as a respectable topic that many neuroscientists took seriously. Because of the legacy of behaviorism, which was strong and long-lasting in neuroscience, consciousness had not been considered a topic that was amenable to the methods of science. The change in the neuroscientific community of the 1990s is largely due to outspoken scientists such as Nobel-laureates Francis Crick and Gerald Edelman, as well as the influence of philosophers such as David Chalmers, Daniel Dennett, and Fred Dretske.

Most neuroscientists believe in the identity of mind and brain, the position of materialism and physicalism. However, some neuroscientists may instead embrace dual-aspect monism, because they do not accept that in postulating an identity between mind and brain (or more specifically, particular types of neuronal interactions) they are implying that mental events are "nothing more" than physical events. Such a neuroscientist would accept that physical events and mental events are different aspects of a more fundamental mental–physical substratum which can be perceived as both mental and physical, depending on perspective. Working neuroscientists do not often address their metaphysical convictions in print, so it may be difficult to know which of these positions they hold (if either), or even whether they distinguish between them.

Since most neuroscientists believe in the identity of mind and brain, it is not surprising that the search for the neural correlate of consciousness (NCC) has become something of a Holy Grail in the neuroscientific community.

Neuroscience has not established an NCC. Future research will reveal how far it can go in discovering such correlates. However, discovering such correlates will not solve the mind–body problem as it is normally posed. To see this, consider that individual theorists with widely differing theoretical perspectives all would have liked to learn the exact empirical correlations between brain processes and conscious states. These theorists include Descartes, Fechner, and the Gestalt psychologists, who had differing outlooks on the mind–brain relation.

To solve the mind–body problem it will not be enough to show that perception or consciousness is correlated with neural processes. Rather, a theoretical solution would need to explain the experienced aspects of perception and consciousness by showing how such aspects can be derived from the activity of neurons (or whatever aspects of brain activity are relevant). No one has proved that such an understanding cannot be achieved (contrary to the dire predictions of the new mysterians). On the other hand, no one really knows what such an understanding would look like. That's why the mind–body problem remains today in the category of unsolved problems. Work toward a solution may be facilitated if theorists are explicit about their assumptions and goals in studying the relations between the mental and the physical.

See also

Notes and citations

- ↑ Kim, J. - (1995 -). Honderich, Ted - Problems in the Philosophy of Mind. Oxford Companion to Philosophy -, -, Oxford -: Oxford University Press -. -.

- ↑ Pinel, J. Psychobiology, (1990) Prentice Hall, Inc. ISBN 8815071741

- ↑ LeDoux, J. (2002) The Synaptic Self: How Our Brains Become Who We Are, New York:Viking Penguin. ISBN 8870787958

- ↑ Russell, S. and Norvig, P. Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach, New Jersey:Prentice Hall. ISBN 0131038052

- ↑ Dawkins, R. The Selfish Gene (1976) Oxford:Oxford University Press. ISBN

- ↑ Gary Hatfield, "The Passions of the Soul and Descartes's machine psychology," Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 38 (2007), 1–35.

- ↑ The mind-body problem by Robert M. Young

- ↑ Turner 1996, p. 76

- ↑ Jaegwon Kim, "Problems in the Philosophy of Mind," in Oxford Companion to Philosophy, Ted Honderich (ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.

- ↑ Colin McGinn, "Can the Mind-Body Problem Be Solved," Mind, n.s. 98 (1989), 349–366.

- ↑ Eckart Scheerer, "The unknown Fechner," Psychological Research 49 (1987), 197–202.

- ↑ William James, Principles of Psychology, 2 vols., New York: Holt, 1890, 1: 182.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Leo M. Hurvich and Dorothea Jameson, "An opponent-process theory of color vision," Psychological Review 64 (1957), 384–404.

- ↑ Gunnar Svaetichin, "Spectral response curves from single cones," Acta Physiologica Scandinavica 39 (supp. 134, 1956), 17–46.

- ↑ Russell L. DeValois, I. Abramov, and Gerald H. Jacobs, "Analysis of response patterns of LGN cells," Journal of the Optical Society of America 56 (1966), 966–77.

- ↑ Davida Y. Teller and Edward N. Pugh, "Linking propositions in color vision," in Colour Vision: Physiology and Psychophysics, John D. Mollon and Lindsey T. Sharpe (eds.), London: Academic Press, 1983, 577–89.

Bibliography

- Descartes, René (1664). L’Homme de René Descartes: et vn traitté de la formation du foetus. Paris: Le Gras.

- Descartes, René (1989). Passions of the Soul, trans. Stephen Voss. Indianapolis: Hackett. Original French version published in 1649.

- Edelman, Gerald M. (2004). Wider Than the Sky: The Phenomenal Gift of Consciousness. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Kim, Jaegwon (2005). Physicalism, or Something Near Enough. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- Seager, William (1999). Theories of Consciousness: An Introduction and Assessment. London: Routledge.

- Shapiro, Lawrence A. (2004). The Mind Incarnate. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

- Turner, Bryan S. (1996). Body and Society: Exploration in social theory

- Velmans, Max, and Susan Schneider (eds.) (2007). Blackwell Companion to Consciousness. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell.

- Zelazo, Philip David, Morris Moscovitch, and Evan Thompson (eds.) (2007). Cambridge Handbook of Consciousness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

External links

- MIND AND BODY: RENÉ DESCARTES TO WILLIAM JAMES, Robert H. Wozniak, Bryn Mawr College – introductory historical overview.

- The Mind-Brain Problem - an introduction for beginners (article in pdf format).

- Sci-Con.org - Science and Consciousness Review, a site maintained by such notables as Bernard Baars, among others.

- David Chalmers' Homepage - a large collection of essays from one of the leading philosophers in the consciousness field.

- Philosophy of the Mind - an index of the mind-body problem.

- Explaining the Mind: Problems, Problems

- Daniel C. Dennett's homepage at Tufts University