Assessment |

Biopsychology |

Comparative |

Cognitive |

Developmental |

Language |

Individual differences |

Personality |

Philosophy |

Social |

Methods |

Statistics |

Clinical |

Educational |

Industrial |

Professional items |

World psychology |

Clinical: Approaches · Group therapy · Techniques · Types of problem · Areas of specialism · Taxonomies · Therapeutic issues · Modes of delivery · Model translation project · Personal experiences ·

The underlying mechanisms of schizophrenia, a mental disorder characterized by a disintegration of the processes of thinking and of emotional responsiveness, are complex. There are a number of theories which attempt to explain the link between altered brain function and schizophrenia.[1] One of the most common is the dopamine hypothesis which attributes psychosis to the mind's faulty interpretation of the misfiring of dopaminergic neurons.[1]

A leading hypothesis treats schizophrenia as a neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disease,[2] in which "developmental insults as early as late first or early second trimester lead to the activation of pathologic neural circuits during adolescence or young adulthood", but critics say the neurodevelopmental hypothesis "does not fully account for a number of features of schizophrenia".[3] The causes of schizophrenia remains poorly understood.[4]

Pathophysiology[]

Particular focus has been placed upon the function of dopamine in the mesolimbic pathway of the brain. This focus largely resulted from the accidental finding that a drug group which blocks dopamine function, known as the phenothiazines, could reduce psychotic symptoms. It is also supported by the fact that amphetamines, which trigger the release of dopamine, may exacerbate the psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia.[5]

An influential theory, known as the Dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia, proposed that excess activation of D2 receptors was the cause of (the positive symptoms of) schizophrenia. Although postulated for about 20 years based on the D2 blockade effect common to all antipsychotics, it was not until the mid-1990s that PET and SPET imaging studies provided supporting evidence. This explanation is now thought to be simplistic, partly because newer antipsychotic medication (called atypical antipsychotic medication) can be equally effective as older medication (called typical antipsychotic medication), but also affects serotonin function and may have slightly less of a dopamine blocking effect.[6]

Interest has also focused on the neurotransmitter glutamate and the reduced function of the NMDA glutamate receptor in schizophrenia. This has largely been suggested by abnormally low levels of glutamate receptors found in postmortem brains of people previously diagnosed with schizophrenia[7] and the discovery that the glutamate blocking drugs such as phencyclidine and ketamine can mimic the symptoms and cognitive problems associated with the condition.[8]

The fact that reduced glutamate function is linked to poor performance on tests requiring frontal lobe and hippocampal function and that glutamate can affect dopamine function, all of which have been implicated in schizophrenia, have suggested an important mediating (and possibly causal) role of glutamate pathways in schizophrenia.[9] Positive symptoms fail however to respond to glutamatergic medication.[10] A commonly known side effect associated with schizo-affective patients known as akathisia (mistaken for schizophrenic symptoms) was found to be associated with increased levels of norepinephrine.[11]

ErbB4 protein abnormalities are also associated with neuropathophysiology of the schizophrenic brain.[12]

Dopamine[]

Template:Unbalanced

- Main article: Dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia

Particular focus has been placed upon the function of dopamine in the mesolimbic pathway of the brain. This focus largely resulted from the accidental finding that a drug group which blocks dopamine function, known as the phenothiazines, could reduce psychotic symptoms. An influential theory, known as the "dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia", proposed that a malfunction involving dopamine pathways was therefore the cause of (the positive symptoms of) schizophrenia.

Evidence for this theory includes[13] findings that the potency of many antipsychotics is correlated with their affinity to dopamine D2 receptors;[14] and the exacerbatory effects of a dopamine agonist (amphetamine) and a dopamine beta hydroxylase inhibitor (disulfiram) on schizophrenia;[15][16] and post-mortem studies initially suggested increased density of dopamine D2 receptors in the striatum. Such high levels of D[2] receptors intensify brain signals in schizophrenia and causes positive symptoms such as hallucinations and paranoia. Impaired glutamate (a neurotransmitter which directs neuron to pass along an impulse) activity appears to be another source of schizophrenia symptoms.[17]

However, there was controversy and conflicting findings over whether postmortem findings resulted from chronic antipsychotic treatment. Compared to the success of postmortem studies in finding profound changes of dopamine receptors, imaging studies using SPET and PET methods in drug naive patients have generally failed to find any difference in dopamine D2 receptor density compared to controls. Comparable findings in longitudinal studies show: " Particular emphasis is given to methodological limitations in the existing literature, including lack of reliability data, clinical heterogeneity among studies, and inadequate study designs and statistic," suggestions are made for improving future longitudinal neuroimaging studies of treatment effects in schizophrenia[18] A recent review of imaging studies in schizophrenia shows confidence in the techniques, while discussing such operator error.[19] In 2007 one report said, "During the last decade, results of brain imaging studies by use of PET and SPET in schizophrenic patients showed a clear dysregulation of the dopaminergic system." [20]

Recent findings from meta-analyses suggest that there may be a small elevation in dopamine D2 receptors in drug-free patients with schizophrenia, but the degree of overlap between patients and controls makes it unlikely that this is clinically meaningful.[21][22] While the review by Laruelle acknowledged more sites were found using methylspiperone, it discussed the theoretical reasons behind such an increase (including the monomer-dimer equilibrium) and called for more work to be done to 'characterise' the differences. In addition, newer antipsychotic medication (called atypical antipsychotic medication) can be as potent as older medication (called typical antipsychotic medication) while also affecting serotonin function and having somewhat less of a dopamine blocking effect. In addition, dopamine pathway dysfunction has not been reliably shown to correlate with symptom onset or severity. HVA levels correlate trendwise to symptoms severity. During the application of debrisoquin, this correlation becomes significant.[23]

Dopamine D2-Like Sites in Schizophrenia, But Not in Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s, or Control Brains for [3H]Benzquinoline ;Synapse Vol 25 1997; pp 137–146; copyright 1997 PHILIP SEEMAN, HONG-CHANG GUAN, JOSE NOBREGA, DILSHAD JIWA, RUDOLPH MARKSTEIN, JA-HYUN BALK, ROBERTO PICETTI, EMILIANA BORRELLI, AND HUBERT H.M. VAN TOL Reprinted with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. No rights are granted to use content that appears in the work with credit to another source. The authors say the D2-like sites detected in this diagram could represent the d4-like sites in other replicated experiments and that these are probably D2 monomers. In the 1997 report, Seeman said more research had to be done into the receptors which were marked by GLC 756. Antipsychotics were found to increase binding sites twofold. “Reprinted with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.”

Giving a more precise explanation of this discrepancy in d2 receptor has been attempted by a significant minority. Radioligand imaging measurements involve the monomer and dimer ratio, and the 'cooperativity' model.[24] Cooperativitiy is a chemical function in the study of enzymes.[25] Dopamine receptors interact with their own kind, or other receptors to form higher order receptors such as dimers, via the mechanism of cooperativity.[26] Philip Seeman has said: "In schizophrenia, therefore, the density of [11C] methylspiperone sites rises, reflecting an increase in monomers, while the density of [11C] raclopride sites remains the same, indicating that the total population of D2 monomers and dimers does not change."[27] (In another place Seeman has said methylspiperone possibly binds with dimers[28]) With this difference in measurement technique in mind, the above mentioned meta-analysis uses results from 10 different ligands.[29] Exaggerated ligand binding results such as SDZ GLC 756 (as used in the figure) were explained by reference to this monomer-dimer equilibrium.

According to Seeman, "...Numerous postmortem studies have consistently revealed D2 receptors to be elevated in the striata of patients with schizophrenia".[30] However, the authors were concerned the effect of medication may not have been fully accounted for. The study introduced an experiment by Abi-Dargham et al.[31] in which it was shown medication-free live schizophrenics had more D2 receptors involved in the schizophrenic process and more dopamine. Since then another study has shown such elevated percentages in d2 receptors is brain-wide (using a different ligand, which did not need dopamine depletion).[32][33] In a 2009 study, Annisa Abi-Dagham et al. confirmed the findings of her previous study regarding increased baseline d2 receptors in schizophrenics and showing a correlation between this magnitude and the result of amphetamine stimulation experiments.[34]

Some animal models of psychosis are similar to those for addiction – displaying increased locomotor activity.[35] For those female animals with previous sexual experience, amphetamine stimulation happens faster than for virgins. There is no study on male equivalent because the studies are meant to explain why females experience addiction earlier than males.[36]

Even in 1986 the effect of antipsychotics on receptor measurement was controversial. An article in Science sought to clarify whether the increase was solely due to medication by using drug-naive schizophrenics: "The finding that D2 dopamine receptors are substantially increased in schizophrenic patients who have never been treated with neuroleptic drugs raises the possibility that dopamine receptors are involved in the schizophrenic disease process itself. Alternatively, the increased D2 receptor number may reflect presynaptic factors such as increased endogenous dopamine levels (16). In either case, our findings support the hypothesis that dopamine receptor abnormalities are present in untreated schizophrenic patients." [37] (The experiment used 3-N-[11C]methylspiperone – the same as mentioned by Seeman detects d2 monomers and binding was double that of controls.)

It is still thought that dopamine mesolimbic pathways may be hyperactive, resulting in hyperstimulation of D2 receptors and positive symptoms. There is also growing evidence that, conversely, mesocortical pathway dopamine projections to the prefrontal cortex might be hypoactive (underactive), resulting in hypostimulation of D1 receptors, which may be related to negative symptoms and cognitive impairment. The overactivity and underactivity in these different regions may be linked, and may not be due to a primary dysfunction of dopamine systems but to more general neurodevelopmental issues that precede them.[38] Increased dopamine sensitivity may be a common final pathway.[39]

Another finding is a six-fold excess of binding sites insensitive to the testing agent, raclopride;[40][41] Seeman said this increase was probably due to the increase in d2 monomers.[27] Such an increase in monomers may occur via the cooperativity mechanism[42] which is responsible for d2high and d2low, the supersensitive and lowsensitivity states of the d2 dopamine receptor.[43] More specifically, "an increase in monomers, may be one basis for dopamine supersensitivity".[44]

Another one of Seeman's findings was that the dopamine D2 receptor protein looked abnormal in schizophrenia. Proteins change states by flexing. The activating of the protein by folding could be permanent or fluctuating,[45] just like the course of patients' illnesses waxes and wanes. Increased folding of a protein leads to increased risk of 'additional fragments' forming.[46] The schizophrenic D2 receptor has a unique additional fragment when digested by papain in the test-tube, but none of the controls exhibited the same fragment.[45] The D2 receptors in schizophrenia are thus in a highly active state as found by Seeman et al.[39]

Glutamate[]

- Main article: Glutamate hypothesis of schizophrenia

Interest has also focused on the neurotransmitter glutamate and the reduced function of the NMDA glutamate receptor in schizophrenia. This has largely been suggested by abnormally low levels of glutamate receptors found in postmortem brains of people previously diagnosed with schizophrenia[7] and the discovery that the glutamate blocking drugs such as phencyclidine and ketamine can mimic the symptoms and cognitive problems associated with the condition.[8]

The fact that reduced glutamate function is linked to poor performance on tests requiring frontal lobe and hippocampal function and that glutamate can affect dopamine function, all of which have been implicated in schizophrenia, have suggested an important mediating (and possibly causal) role of glutamate pathways in schizophrenia.[9] Further support of this theory has come from preliminary trials suggesting the efficacy of coagonists at the NMDA receptor complex in reducing some of the positive symptoms of schizophrenia.[10]

Structural findings[]

Studies have tended to show various subtle average differences in the volume of certain areas of brain structure between people with and without diagnoses of schizophrenia, although it has become increasingly clear that there is no single pathological neuropsychological or structural neuroanatomic profile, due partly to heterogeneity within the disorder.[47]

Neurological[]

Those with a diagnosis of schizophrenia have both changes in brain structure and brain chemistry, including dopamine.[1] Studies using neuropsychological tests and brain imaging technologies such as fMRI and PET to examine functional differences in brain activity have shown that differences seem to most commonly occur in the frontal lobes, hippocampus and temporal lobes.[48] Due to the alteration in neural circuits some[attribution needed] feel schizophrenia should be viewed as a collection of neurodevelopmental disorders.[49] These differences have been linked to the neurocognitive deficits often associated with schizophrenia.[50]

The past 30 years of brain imaging supports the neurobiological pathologies of psychiatric diseases.[51] The neurobiological abnormalities are so varied that no single abnormality is observed across the entire group of people with DSM-IV–defined schizophrenia. In addition, it remains unclear whether the structural differences are unique to schizophrenia or cut across the traditional diagnostic boundaries between schizophrenia and affective disorders - though perhaps being unique to conditions with psychotic features.[52]

Studies of the rare childhood-onset schizophrenia (before age 13) indicate a greater-than-normal loss of grey matter over several years, progressing from the back of the brain to the front, leveling out in early adulthood. Such a pattern of "pruning" occurs as part of normal brain development but appears to be exaggerated in childhood-onset psychotic diagnoses, particularly schizophrenia. Abnormalities in the volume of the ventricles or frontal lobes have also been found in several studies but not in others. Volume changes are most likely glial and vascular rather than purely neuronal, and reduction in grey matter may primarily reflect a reduction of neuropil rather than a deficit in the total number of neurons. Other studies, especially some computational studies, have shown that a reduction in the number of neurons can cause psychotic symptoms.[53] Studies to date have been based on small numbers of the most severe and treatment-resistant patients taking antipsychotics.[54]

The most consistent volumetric findings are (first-onset patient vs control group averages), slightly less grey matter volume and slightly increased ventricular volume in certain areas of the brain. The two findings are thought to be linked. Although the differences are found in first-episode cases, grey matter volumes are partly a result of life experiences, drugs and malnutrition etc., so the exact role in the disorder is unclear.[4]

In addition, ventricle volumes are amongst the mostly highly variable and environmentally influenced aspects of brain structure, and the percentage difference in group averages in schizophrenia studies has been described as "not a very profound difference in the context of normal variation."[55] A slightly smaller than average whole-brain volume has also been found, and slightly smaller hippocampal volume in terms of group averages. These differences may be present from birth or develop later, and there is substantial variation between individuals.[4]

MRI[]

There have also been findings of differences in the size and structure of certain brain areas in schizophrenia. A 2006 metaanlaysis of MRI studies found that whole brain and hippocampal volume are reduced and that ventricular volume is increased in patients with a first psychotic episode relative to healthy controls. The average volumetric changes in these studies are however close to the limit of detection by MRI methods, so it remains to be determined whether schizophrenia is a neurodegenerative process that begins at about the time of symptom onset, or whether it is better characterised as a neurodevelopmental process that produces abnormal brain volumes at an early age.[4] In first episode psychosis typical antipsychotics like haloperidol were associated with significant reductions in gray matter volume, whereas atypical antipsychotics like olanzapine were not.[56] Studies in non-human primates found gray and white matter reductions for both typical and atypical antipsychotics.[57]

Abnormal findings in the prefrontal cortex, temporal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex are found before the first onset of schizophrenia symptoms. These regions are the regions of structural deficits found in schizophrenia and first-episode patients.[58]

Positive symptoms, such as thoughts of being persecuted, were found to be related to the medial prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and hippocampus region. Negative symptoms were found to be related to the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex and ventral striatum.[58]

Ventricular and third ventricle enlargement, abnormal functioning of the amygdala, hippocampus, parahippocampal gyrus, neocortical temporal lobe regions, frontal lobe, prefontal gray matter, orbitofrontal areas, parietal lobs abnormalities and subcortical abnormalities including the cavum septi, pellucidi, basal ganglia, corpus callosum, thalamus and cerebellar abnormalities. Such abnormalities usually present in the form of loss of volume.[2]

Most schizophrenia studies have found average reduced volume of the left medial temporal lobe and left superior temporal gyrus, and half of studies have revealed deficits in certain areas of the frontal gyrus, parahippocampal gyrus and temporal gyrus.[59] However, at variance with some findings in individuals with chronic schizophrenia significant group differences of temporal lobe and amygdala volumes are not shown in first-episode patients on average.[60]

fMRI[]

Functional magnetic resonance imaging and other brain imaging technologies allow for the study of differences in brain activity among people diagnosed with schizophrenia

The use of functional MRI (fMRI) with cognitive behavioral science allows scientists to investigate and uncover areas of the brain that are not working appropriately in the schizophrenic brain, leading the behavioral deficits. Through this effort there have been several areas of the brain that are responsible for cognitive processing that have been identified to be malfunctioning in the schizophrenic brain. These studies have demonstrated abnormalities at the early steps of sensory processing. This may influence further errors when it comes to more comprehensive and complex evaluation processing, which compounds the problem.[61]

DT-MRI[]

Diffusion tensor MRI (DTI) allows for the investigation of white matter more closely than traditional MRI.[2] A 2009 meta-analysis of diffusion tensor imaging studies identified two consistent locations of reduced fractional anisotropy (roughly the level of organization of neural connections) in schizophrenia. This suggest that two networks of white matter tracts may be affected in schizophrenia, with the potential for "disconnection" of the gray matter regions which they link.[62] Reduced anisotropy levels of white matter integrity and decreased anisotropy in thesplenium of the corpus callosum.[2]

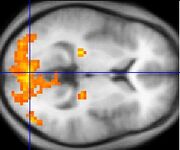

PET[]

Data from a PET study[63] suggests that the less the frontal lobes are activated (red) during a working memory task, the greater the increase in abnormal dopamine activity in the striatum (green), thought to be related to the neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia.

PET scanning is a useful tool to allow the imaging of brain physiology.[64] PET is useful to elaborate hypothesis of the origins of brain pathology, to relate symptoms to biological variables and to study individuals at increased risk. Studies measuring cerebral metabolic rate for glucose (CMRglc) and cerebral blood flow (CBF) have indicated an indirect measurement of synaptic activity. The ability to detect dysfunction of the communication between glutamatergic neurons and astrocytes may lead to an increased understanding of altered functional brain images.[65]

PET scan findings indicate cerebral blood flow decreases in the left parahippocampal region. PET scans also show a reduced ability to metabolize glucose in the thalamus and frontal cortex. PET scans also show involvement of the medial part of the left temporal lobe and the limbic and frontal systems as suffering from developmental abnormality. PET scans show thought disorders stem from increased flow in the frontal and temporal regions while delusions and hallucinations were associated with reduced flow in the cingulate, left frontal, and temporal areas. PET scans done on patient who were actively having auditory hallucinations revealed increased blood flow in both thalami, left hippocampus, right striatum, parahippocampus, orbitofrontal, and cingulate areas.[2]

CT[]

Computed Tomography scans of schiznoprenic brains show several pathologies. The brain ventricles are enlarged as compared to normal brains. The ventricles hold cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and enlarged ventricles indicate a loss of brain volume. Additionally, schizophrenic brains have widened sulci as compared to normal brains, also with increased CSF volumes and reduced brain volume.[2][66]

EEG[]

Electroencephalograms (EEG) measure the electrical impulses on the surface of the brain. EEGs have demonstrated abnormalities of the P300 waveform in cortical event related potentials including nerve voltage conduction in the temporal lobe in both right-handed and left-handed schizophrenics.[66][67]

Other[]

Dyregulation of neural calcium homeostasis has been hypothesized to be a link between the glutamate and dopaminergic abnormalities[68] and some small studies have indicated that calcium channel blocking agents can lead to improvements on some measures in schizophrenia with tardive dyskinesia.[69]

There is evidence of irregular cellular metabolism and oxidative stress in the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia, involving increased glucose demand and/or cellular hypoxia.[70]

Mutations in the gene for brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) have been reported to be a risk factor for the disease.[71]

References[]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 van Os J, Kapur S. Schizophrenia. Lancet. 2009;374(9690):635–45. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60995-8. PMID 19700006.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Shenton ME, Dickey CC, Frumin M, McCarley RW. A review of MRI findings in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2001;49(1-2):1–52. PMID 11343862.

- ↑ Fatemi SH, Folsom TD. The neurodevelopmental hypothesis of schizophrenia, revisited. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(3):528–48. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbn187. PMID 19223657.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Steen RG, Mull C, McClure R, Hamer RM, Lieberman JA. Brain volume in first-episode schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis of magnetic resonance imaging studies. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:510–8. doi:10.1192/bjp.188.6.510. PMID 16738340.

- ↑ Laruelle M, Abi-Dargham A, van Dyck CH, et al. Single photon emission computerized tomography imaging of amphetamine-induced dopamine release in drug-free schizophrenic subjects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93(17):9235–40. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.17.9235. PMID 8799184.

- ↑ Jones HM, Pilowsky LS. Dopamine and antipsychotic drug action revisited. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181:271–5. doi:10.1192/bjp.181.4.271. PMID 12356650.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Konradi C, Heckers S. Molecular aspects of glutamate dysregulation: implications for schizophrenia and its treatment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2003;97(2):153–79. doi:10.1016/S0163-7258(02)00328-5. PMID 12559388.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Lahti AC, Weiler MA, Tamara Michaelidis BA, Parwani A, Tamminga CA. Effects of ketamine in normal and schizophrenic volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25(4):455–67. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00243-3. PMID 11557159.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Coyle JT, Tsai G, Goff D. Converging evidence of NMDA receptor hypofunction in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2003;1003:318–27. doi:10.1196/annals.1300.020. PMID 14684455.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Tuominen HJ, Tiihonen J, Wahlbeck K. Glutamatergic drugs for schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 2005;72(2-3):225–34. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2004.05.005. PMID 15560967. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Touminen2005" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ http://books.google.com/books?id=AQeQa5AtpXoC&pg=PA215&lpg=PA215&source=bl&ots=_AZBdDkZOg&sig=cyrLwQRUUijGlvTRNVpmKoLJmpc&hl=en&ei=C9HMTI3mJ5DSsAPbhNzzDg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CBcQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ↑ Lu CL, Wang YC, Chen JY, Lai IC, Liou YJ. Support for the involvement of the ERBB4 gene in schizophrenia: a genetic association analysis. Neurosci. Lett. 2010;481(2):120–5. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2010.06.067. PMID 20600594.

- ↑ Template:Vcite book

- ↑ Creese I, Burt DR, Snyder SH. Dopamine receptor binding predicts clinical and pharmacological potencies of antischizophrenic drugs. Science (journal). 1976;192(4238):481–3. doi:10.1126/science.3854. PMID 3854.

- ↑ Angrist B, van Kammen DP. CNS stimulants as a tool in the study of schizophrenia. Trends in Neurosciences. 1984;7:388–90. doi:10.1016/S0166-2236(84)80062-4.

- ↑ Lieberman JA, Kane JM, Alvir J. Provocative tests with psychostimulant drugs in schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl.). 1987;91(4):415–33. doi:10.1007/BF00216006. PMID 2884687.

- ↑ Myers DG. Schizophrenia. Psychology. 2007:678–85.

- ↑ Davis C, Jeste D, Eyler L. Review of longitudinal functional neuroimaging studies of drug treatments in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 1 October 2005;78(1):45–60. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2005.05.009. PMID 15979287.

- ↑ Gur RE, Chin S. Laterality in functional brain imaging studies of schizophrenia.. Schizophrenia bulletin. 1999;25(1):141–56. PMID 10098918.

- ↑ Meisenzahl EM, Schmitt GJ, Moller HJ. The role of dopamine for the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. International Review of Psychiatry. 2007;19(4):337–45. doi:10.1080/09540260701502468. PMID 17671867.

- ↑ Laruelle M. Imaging dopamine transmission in schizophrenia. A review and meta-analysis. Q J Nucl Med. 1998;42(3):211–21. PMID 9796369.

- ↑ Stone JM, Morrison PD, Pilowsky LS. Review: Glutamate and dopamine dysregulation in schizophrenia a synthesis and selective review. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2006;21(4):440–52. doi:10.1177/0269881106073126. PMID 17259207.

- ↑ Maas JW, Contreras SA, Seleshi E, Bowden CL. Dopamine metabolism and disposition in schizophrenic patients. Studies using debrisoquin. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45(6):553–9. PMID 3377641.

- ↑ Seeman P, Schwarz J, Chen JF, Szechtman H, Perreault M, McKnight GS, Roder JC, Quirion R, Boksa P, Srivastava LK, Yanai K, Weinshenker D, Sumiyoshi T. Psychosis pathways converge via D2high dopamine receptors. Synapse. 2006 Sep 15; 60(4):319-46

- ↑ Safra, JE (Chairman) 2005 'Cooperativity' The New Encyclopaedia Britannica, Vol 3, Micropaedia, p 666

- ↑ Fuxe K, Marcellino D, Guidolin D, Woods A, Agnati L, "Chapter 10 - Dopamine Receptor Oligermization", in Neve KA (ed)'Dopamine Receptors' Springer (2009) http://books.google.com/books?id=9DBnY_R-Mt0C&pg=PA261&dq=schizophrenia+cooperativity+receptor&hl=en&ei=7gROTdHWMISKuAPotODPDw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=3&ved=0CDMQ6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=dopamine%20receptor%20oligomerization&f=false

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 http://www.acnp.org/G4/GN401000027/CH027.html

- ↑ European Journal of Pharmacology: Molecular Pharmacology Volume 227, Issue 2, 1 October 1992, Pages 139-146 doi:10.1016/0922-4106(92)90121-B 1992 Published by Elsevier Science B.V. The cloned dopamine D2 receptor reveals different densities for dopamine receptor antagonist ligands. Implications for human brain positron emission tomography Philip Seemana, b, Corresponding Author Contact Information, Hong-chang Guana, Olivier Civellic, Hubert H. M. Van Tolb, d, a, Roger K. Sunaharaa and Hyman B. Niznikd, b

- ↑ Zakzanis KK, Hansen KT. Dopamine D2 densities and the schizophrenic brain. Schizophrenia research. 1998;32(3):201–6. PMID 9720125.

- ↑ Seeman P, Kapur S. Schizophrenia: more dopamine, more D2 receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97(14):7673–5. PMID 10884398.

- ↑ Abi-Dargham A, Rodenhiser J, Printz D, et al. Increased baseline occupancy of D2 receptors by dopamine in schizophrenia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.. 2000;97(14):8104–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.14.8104. PMID 10884434.

- ↑ Vernaleken I, Eickhoff S, Veselinovic T, et al. Elevated D2/3-receptor availability in schizophrenia: A [18F]fallypride study. NeuroImage. 2008;41:T145. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.04.113.

- ↑ Cropley VL, Innis RB, Nathan PJ, et al. Small effect of dopamine release and no effect of dopamine depletion on 18Ffallypride binding in healthy humans.. Synapse. 2008;62(6):399–408. doi:10.1002/syn.20506. PMID 18361438.

- ↑ Abi-Dargham A, Elsmarieke E, Slifstein M, Kegeles LS, Laruelle M. Baseline and Amphetamine-Stimulated Dopamine Activity Are Related in Drug-Naïve Schizophrenic Subjects. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;65(12):1091–3. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.12.007. PMID 19167701.

- ↑ http://www.schizophreniaforum.org/new/detail.asp?id=1288 "Amphetamine psychosis has been proposed as a model for some features of schizophrenia... This model of amphetamine sensitization has also been adopted as a paradigm for researchers interested in the addictive powers of drugs of abuse."

- ↑ Bradley KC, Meisel RL. Sexual Behavior Induction of c-Fos in the Nucleus Accumbens and Amphetamine-Stimulated Locomotor Activity Are Sensitized by Previous Sexual Experience in Female Syrian Hamsters. J. Neurosci. 2001;21(6):2123–30. PMID 11245696.

- ↑ Wong DF, Wagner H, Tune L, et al. Positron emission tomography reveals elevated D2 dopamine receptors in drug-naive schizophrenics. Science. 1986;234(4783):1558–63. doi:10.1126/science.2878495. PMID 2878495.

- ↑ Abi-Dargham A, Moore H. Prefrontal DA transmission at D1 receptors and the pathology of schizophrenia. Neuroscientist. 2003;9(5):404–16. doi:10.1177/1073858403252674. PMID 14580124.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Seeman P, Schwarz J, Chen JF, et al. Psychosis pathways converge via D2high dopamine receptors. Synapse. 2006;60(4):319–46. doi:10.1002/syn.20303. PMID 16786561.

- ↑ Seeman P, Guan H-C, Van Tol HH. Dopamine D4 receptors elevated in schizophrenia. Nature. 1993;365(6445):441. doi:10.1038/365441a0. PMID 8413587.

- ↑ For a discussion of opposing studies see p 143: Seeman P, Guan H-C, Nobrega J et al. Synapse. 1997;25(2):137–46. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199702)25:2<137::AID-SYN4>3.0.CO;2-D. PMID 9021894.

- ↑ Levitzki A, Schlessinger J. Cooperativity in associating proteins. Monomer-dimer equilibrium coupled to ligand binding. Biochemistry. 1974;13(25):5214–9. doi:10.1021/bi00722a026. PMID 4433518.

- ↑ Seeman P. All Psychotic Roads Lead to Increased Dopamine D2High Receptors: A Perspective. Clinical Schizophrenia & Related Psychoses. 2008;1:351–5. doi:10.3371/CSRP.1.4.7.

- ↑ Seeman P, Van Tol HH. Dopamine receptor pharmacology.. Trends in pharmacological sciences. 1994;15(7):264–70. PMID 7940991.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Seeman P, Niznik HB. Dopamine receptors and transporters in Parkinson's disease and schizophrenia. FASEB Journal. 1990;4:2737–44.

- ↑ Rote KV, Rechsteiner M. Degradation of proteins microinjected into HeLa cells. The role of substrate flexibility [PDF]. J. Biol. Chem.. 1986;261(33):15430–6. PMID 2430958.

- ↑ Flashman LA, Green MF. Review of cognition and brain structure in schizophrenia: profiles, longitudinal course, and effects of treatment. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 2004;27(1):1–18, vii. doi:10.1016/S0193-953X(03)00105-9. PMID 15062627.

- ↑ Template:Vcite book

- ↑ Insel TR. Rethinking schizophrenia. Nature. 2010;468(7321):187–93. doi:10.1038/nature09552. PMID 21068826.

- ↑ Green MF. Cognitive impairment and functional outcome in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder [PDF]. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67 Suppl 9:3–8; discussion 36–42. PMID 16965182.

- ↑ Agarwal N, Port JD, Bazzocchi M, Renshaw PF. Update on the use of MR for assessment and diagnosis of psychiatric diseases. Radiology. 2010;255(1):23–41. doi:10.1148/radiol.09090339. PMID 20308442.

- ↑ Prasad KM, Keshavan MS. Structural cerebral variations as useful endophenotypes in schizophrenia: do they help construct "extended endophenotypes"?. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34(4):774–90. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbn017. PMID 18408230.

- ↑ Hoffman R, McGlashan T. Neural network models of schizophrenia.. Neuroscientist. 2001;7(5):441–54. doi:10.1177/107385840100700513. PMID 11597103.

- ↑ Arango C, Moreno C, Martínez S, et al. Longitudinal brain changes in early-onset psychosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2008;34(2):341–53. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbm157. PMID 18234701.

- ↑ Allen JS, Damasio H, Grabowski TJ. Normal neuroanatomical variation in the human brain: an MRI-volumetric study. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2002;118(4):341–58. doi:10.1002/ajpa.10092. PMID 12124914.

- ↑ Lieberman JA, Bymaster FP, Meltzer HY, et al. Antipsychotic drugs: comparison in animal models of efficacy, neurotransmitter regulation, and neuroprotection. Pharmacol. Rev. 2008;60(3):358–403. doi:10.1124/pr.107.00107. PMID 18922967.

- ↑ DeLisi LE. The concept of progressive brain change in schizophrenia: implications for understanding schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34(2):312–21. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbm164. PMID 18263882.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Jung WH, Jang JH, Byun MS, An SK, Kwon JS. Structural Brain Alterations in Individuals at Ultra-high Risk for Psychosis: A Review of Magnetic Resonance Imaging Studies and Future Directions. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2010;25(12):1700–9. doi:10.3346/jkms.2010.25.12.1700. PMID 21165282.

- ↑ Honea R, Crow TJ, Passingham D, Mackay CE. Regional deficits in brain volume in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of voxel-based morphometry studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(12):2233–45. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.12.2233. PMID 16330585.

- ↑ Vita A, De Peri L, Silenzi C, Dieci M. Brain morphology in first-episode schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of quantitative magnetic resonance imaging studies. Schizophr. Res. 2006;82(1):75–88. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2005.11.004. PMID 16377156.

- ↑ Gur RE, Gur RC. Functional magnetic resonance imaging in schizophrenia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2010;12(3):333–43. PMID 20954429.

- ↑ Ellison-Wright I, Bullmore E. Meta-analysis of diffusion tensor imaging studies in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2009;108(1-3):3–10. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2008.11.021. PMID 19128945.

- ↑ Meyer-Lindenberg A, Miletich RS, Kohn PD, et al. Reduced prefrontal activity predicts exaggerated striatal dopaminergic function in schizophrenia. Nat. Neurosci. 2002;5(3):267–71. doi:10.1038/nn804. PMID 11865311.

- ↑ Vyas NS, Patel NH, Nijran KS, Al-Nahhas A, Puri BK. The use of PET imaging in studying cognition, genetics and pharmacotherapeutic interventions in schizophrenia. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11(1):37–51. doi:10.1586/ern.10.160. PMID 21158554.

- ↑ Giovacchini G, Ferdinando S, Esmaeilzadeh M, Amalia M, Luigi M, Ciarmiello A. Pet translates neurophysiology in images : A review to stimulate a network between neuroimaging and basic research. J. Cell. Physiol. 2010. doi:10.1002/jcp.22451. PMID 20945377.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Template:Vcite book

- ↑ Holinger DP, Faux SF, Shenton ME, et al. Reversed temporal region asymmetries of P300 topography in left- and right-handed schizophrenic subjects. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1992;84(6):532–7. doi:10.1016/0168-5597(92)90042-A. PMID 1280199.

- ↑ Yarlagadda A. Role of calcium regulation in pathophysiology model of schizophrenia and possible interventions. Med. Hypotheses. 2002;58(2):182–6. doi:10.1054/mehy.2001.1511. PMID 11812200.

- ↑ Yamada K, Ashikari I, Onishi K, Kanba S, Yagi G, Asai M. Effectiveness of nilvadipine in two cases of chronic schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 1995;49(4):237–8. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.1995.tb01891.x. PMID 9179944.

- ↑ Prabakaran S, Swatton JE, Ryan MM, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in schizophrenia: evidence for compromised brain metabolism and oxidative stress. Mol. Psychiatry. 2004;9(7):684–97, 643. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001511. PMID 15098003.

- ↑ Xu MQ, St Clair D, Feng GY, et al. BDNF gene is a genetic risk factor for schizophrenia and is related to the chlorpromazine-induced extrapyramidal syndrome in the Chinese population. Pharmacogenet. Genomics. 2008;18(6):449–57. doi:10.1097/FPC.0b013e3282f85e26. PMID 18408624.

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia (view authors). |