(corrected format issue) |

|||

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

===Chemical basis=== |

===Chemical basis=== |

||

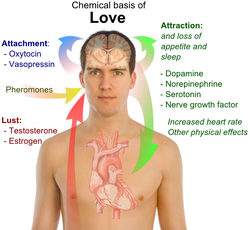

[[File:Chemical basis of love.png|thumb|left|250px|Simplified overview of the chemical basis of love.]] |

[[File:Chemical basis of love.png|thumb|left|250px|Simplified overview of the chemical basis of love.]] |

||

| + | |||

| − | {{main|Love ( |

+ | {{main|Love (biological basis)} |

Biological models of sex tend to view love as a [[mammal]]ian drive, much like [[hunger]] or [[thirst]].<ref name="Lewis">{{cite book | last = Lewis | first = Thomas | coauthors = Amini, F., & Lannon, R. | title = A General Theory of Love | publisher = Random House | year = 2000 |isbn=0-375-70922-3}}</ref> [[Helen Fisher (anthropologist)|Helen Fisher]], a leading expert in the topic of love, divides the experience of love into three partly overlapping stages: lust, attraction, and attachment. Lust exposes people to others; romantic attraction encourages people to focus their energy on mating; and attachment involves tolerating the spouse (or indeed the child) long enough to rear a child into infancy. |

Biological models of sex tend to view love as a [[mammal]]ian drive, much like [[hunger]] or [[thirst]].<ref name="Lewis">{{cite book | last = Lewis | first = Thomas | coauthors = Amini, F., & Lannon, R. | title = A General Theory of Love | publisher = Random House | year = 2000 |isbn=0-375-70922-3}}</ref> [[Helen Fisher (anthropologist)|Helen Fisher]], a leading expert in the topic of love, divides the experience of love into three partly overlapping stages: lust, attraction, and attachment. Lust exposes people to others; romantic attraction encourages people to focus their energy on mating; and attachment involves tolerating the spouse (or indeed the child) long enough to rear a child into infancy. |

||

Revision as of 16:07, 10 August 2009

Assessment |

Biopsychology |

Comparative |

Cognitive |

Developmental |

Language |

Individual differences |

Personality |

Philosophy |

Social |

Methods |

Statistics |

Clinical |

Educational |

Industrial |

Professional items |

World psychology |

Personality: Self concept · Personality testing · Theories · Mind-body problem

| Part of a series on Love |

| Historically |

|---|

| Agape |

| Eros |

| Philia |

| Storge |

| Courtly love |

| Religious love |

| Grades of Emotion |

| Brotherly love |

| Sisterly love |

| Erotic love |

| Platonic love |

| Familial love |

| Puppy love |

| Romantic love |

| See Also |

| Unrequited love |

| Celibacy |

| Sexuality |

| Asexuality |

| Sex |

Love is any of a number of emotions and experiences related to a sense of strong affection[1] and attachment. The word love can refer to a variety of different feelings, states, and attitudes, ranging from generic pleasure ("I loved that meal") to intense interpersonal attraction ("I love my boyfriend"). This diversity of uses and meanings, combined with the complexity of the feelings involved, makes love unusually difficult to consistently define, even compared to other emotional states.

As an abstract concept, love usually refers to a deep, ineffable feeling of tenderly caring for another person. Even this limited conception of love, however, encompasses a wealth of different feelings, from the passionate desire and intimacy of romantic love to the nonsexual emotional closeness of familial and platonic love[2] to the profound oneness or devotion of religious love.[3] Love in its various forms acts as a major facilitator of interpersonal relationships and, owing to its central psychological importance, is one of the most common themes in the creative arts.

Definitions

Museum of Anthropology in Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico.

The English word "love" can have a variety of related but distinct meanings in different contexts. Often, other languages use multiple words to express some of the different concepts that English relies mainly on "love" to encapsulate; one example is the plurality of Greek words for "love." Cultural differences in conceptualizing love thus make it doubly difficult to establish any universal definition.[4]

Although the nature or essence of love is a subject of frequent debate, different aspects of the word can be clarified by determining what isn't love. As a general expression of positive sentiment (a stronger form of like), love is commonly contrasted with hate (or neutral apathy); as a less sexual and more emotionally intimate form of romantic attachment, love is commonly contrasted with lust; and as an interpersonal relationship with romantic overtones, love is commonly contrasted with friendship, although other definitions of the word love may be applied to close friendships in certain contexts.

When discussed in the abstract, love usually refers to interpersonal love, an experience felt by a person for another person. Love often involves caring for or identifying with a person or thing, including oneself (cf. narcissism).

In addition to cross-cultural differences in understanding love, ideas about love have also changed greatly over time. Some historians date modern conceptions of romantic love to courtly Europe during or after the Middle Ages, although the prior existence of romantic attachments is attested by ancient love poetry.[5]

Impersonal love

A person can be said to love a country, principle, or goal if they value it greatly and are deeply committed to it. Similarly, compassionate outreach and volunteer workers' "love" of their cause may sometimes be borne not of interpersonal love, but impersonal love coupled with altruism and strong political convictions. People can also "love" material objects, animals, or activities if they invest themselves in bonding or otherwise identifying with those things. If sexual passion is also involved, this condition is called paraphilia.[6]

Interpersonal love

Archetypal lovers Romeo and Juliet portrayed by Frank Bernard Dicksee.

Interpersonal love refers to love between human beings. It is a more potent sentiment than a simple liking for another. Unrequited love refers to those feelings of love that are not reciprocated. Interpersonal love is most closely associated with interpersonal relationships. Such love might exist between family members, friends, and couples. There are also a number of psychological disorders related to love, such as erotomania.

Throughout history, philosophy and religion have done the most speculation on the phenomenon of love. In the last century, the science of psychology has written a great deal on the subject. In recent years, the sciences of evolutionary psychology, evolutionary biology, anthropology, neuroscience, and biology have added to the understanding of the nature and function of love.

Chemical basis

Simplified overview of the chemical basis of love.

{{main|Love (biological basis)}

Biological models of sex tend to view love as a mammalian drive, much like hunger or thirst.[7] Helen Fisher, a leading expert in the topic of love, divides the experience of love into three partly overlapping stages: lust, attraction, and attachment. Lust exposes people to others; romantic attraction encourages people to focus their energy on mating; and attachment involves tolerating the spouse (or indeed the child) long enough to rear a child into infancy.

Lust is the initial passionate sexual desire that promotes mating, and involves the increased release of chemicals such as testosterone and estrogen. These effects rarely last more than a few weeks or months. Attraction is the more individualized and romantic desire for a specific candidate for mating, which develops out of lust as commitment to an individual mate forms. Recent studies in neuroscience have indicated that as people fall in love, the brain consistently releases a certain set of chemicals, including pheromones, dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin, which act in a manner similar to amphetamines, stimulating the brain's pleasure center and leading to side effects such as increased heart rate, loss of appetite and sleep, and an intense feeling of excitement. Research has indicated that this stage generally lasts from one and a half to three years.[8]

Since the lust and attraction stages are both considered temporary, a third stage is needed to account for long-term relationships. Attachment is the bonding that promotes relationships lasting for many years and even decades. Attachment is generally based on commitments such as marriage and children, or on mutual friendship based on things like shared interests. It has been linked to higher levels of the chemicals oxytocin and vasopressin to a greater degree than short-term relationships have.[8]

The protein molecule known as the nerve growth factor (NGF) has high levels when people first fall in love, but these return to previous levels after one year. [9]

Psychological basis

- Further information: Human bonding

Grandmother and grandchild,

Sri Lanka

Psychology depicts love as a cognitive and social phenomenon. Psychologist Robert Sternberg formulated a triangular theory of love and argued that love has three different components: intimacy, commitment, and passion. Intimacy is a form in which two people share confidences and various details of their personal lives, and is usually shown in friendships and romantic love affairs. Commitment, on the other hand, is the expectation that the relationship is permanent. The last and most common form of love is sexual attraction and passion. Passionate love is shown in infatuation as well as romantic love. All forms of love are viewed as varying combinations of these three components. American psychologist Zick Rubin seeks to define love by psychometrics. His work states that three factors constitute love: attachment, caring, and intimacy.[10] [11]

Following developments in electrical theories such as Coulomb's law, which showed that positive and negative charges attract, analogs in human life were developed, such as "opposites attract." Over the last century, research on the nature of human mating has generally found this not to be true when it comes to character and personality—people tend to like people similar to themselves. However, in a few unusual and specific domains, such as immune systems, it seems that humans prefer others who are unlike themselves (e.g., with an orthogonal immune system), since this will lead to a baby that has the best of both worlds.[12] In recent years, various human bonding theories have been developed, described in terms of attachments, ties, bonds, and affinities.

Some Western authorities disaggregate into two main components, the altruistic and the narcissistic. This view is represented in the works of Scott Peck, whose work in the field of applied psychology explored the definitions of love and evil. Peck maintains that love is a combination of the "concern for the spiritual growth of another," and simple narcissism.[13] In combination, love is an activity, not simply a feeling.

Comparison of scientific models

Biological models of love tend to see it as a mammalian drive, similar to hunger or thirst.[7] Psychology sees love as more of a social and cultural phenomenon. There are probably elements of truth in both views. Certainly love is influenced by hormones (such as oxytocin), neurotrophins (such as NGF), and pheromones, and how people think and behave in love is influenced by their conceptions of love. The conventional view in biology is that there are two major drives in love: sexual attraction and attachment. Attachment between adults is presumed to work on the same principles that lead an infant to become attached to its mother. The traditional psychological view sees love as being a combination of companionate love and passionate love. Passionate love is intense longing, and is often accompanied by physiological arousal (shortness of breath, rapid heart rate); companionate love is affection and a feeling of intimacy not accompanied by physiological arousal.

Studies have shown that brain scans of those infatuated by love display a resemblance to those with a mental illness. Love creates activity in the same area of the brain where hunger, thirst, and drug cravings create activity. New love, therefore, could possibly be more physical than emotional. Over time, this reaction to love mellows, and different areas of the brain are activated, primarily ones involving long-term commitments. Dr. Andrew Newberg, a neuroscientist, suggests that this reaction to love is so similar to that of drugs because without love, humanity would die out.[How to reference and link to summary or text]

Philosophical views

People, throughout history, have often considered phenomena such as "love at first sight" or "instant friendships" to be the result of an uncontrollable force of attraction or affinity.[14] One of the first to theorize in this direction was the Greek philosopher Empedocles, who in the 4th century BC argued for the existence of two forces, love (philia) and strife (neikos), which were used to account for the causes of motion in the universe. These two forces were said to intermingle with the classical elements, i.e., earth, water, air, and fire, in such a manner that love served as the binding power linking the various parts of existence harmoniously together.

Later, Plato interpreted Empedocles' two agents as attraction and repulsion, stating that their operation is conceived in an alternate sequence.[15] From these arguments, Plato originated the concept of "likes attract", e.g., earth is attracted to earth, water to water, and fire to fire. In modern terms this is often phrased in terms of "birds of a feather flock together".

Bertrand Russell describes love as a condition of "absolute value", as opposed to relative value. Thomas Jay Oord defines love as acting intentionally, in sympathetic response to others (including God), to promote overall well-being. Oord means for his definition to be adequate for religion, philosophy, and the sciences. Robert Anson Heinlein, one of the most prolific science fiction writers of the 20th century, defined love in his novel Stranger in a Strange Land as the point of emotional connection which leads to the happiness of another being essential to one's own well being. This definition ignores the ideas of religion and science and instead focuses on the meaning of love as it relates to the individual.

Religious views

- Main article: Love (religious views)

Love in early religions was a mixture of ecstatic devotion and ritualised obligation to idealised natural forces (pagan polytheism).[How to reference and link to summary or text] Later religions shifted emphasis towards single abstractly-oriented objects like God, law, church and state (formalised monotheism). A third view, pantheism, recognises a state or truth distinct from (and often antagonistic to) the idea that there is a difference between the worshiping subject and the worshiped object. Love is reality, of which we, moving through time, imperfectly interpret ourselves as an isolated part.[How to reference and link to summary or text]

The Bible speaks of love as a set of attitudes and actions that are far broader than the concept of love as an emotional attachment. Love is seen as a set of behaviours that humankind is encouraged to act out. One is encouraged not just to love one's partner, or even one's friends but also to love one's enemies. The Bible describes this type of active love in 1 Corinthians 13:4-8:

| “ | Love is patient, love is kind. It does not envy, it does not boast, it is not proud. It is not rude, it is not self-seeking, it is not easily angered, it keeps no record of wrongs. Love does not delight in evil but rejoices with the truth. It always protects, always trusts, always hopes, always perseveres. Love never fails. | ” |

Romantic love is also present in the Bible, particularly the Song of Songs. Traditionally, this book has been interpreted allegorically as a picture of God's love for Israel and the Church. When taken naturally, we see a picture of ideal human marriage:[16]

| “ | Place me like a seal over your heart, like a seal on your arm; for love is as strong as death, its jealously unyielding as the grave. It burns like a blazing fire, like a mighty flame. Many waters cannot quench love; rivers cannot wash it away. If one were to give all the wealth of his house for love, it would be utterly scorned. | ” |

The passage dodi li v'ani lo, i.e. "my beloved is mine and I am my beloved", from Song of Songs 2:16, is an example of a biblical quote commonly engraved on wedding bands.

Also, the Bible defines love as being God himself. I John 4:8 states "God is Love". In essence, God is the epitomy of love - in action and relation.[How to reference and link to summary or text] It is God that first loved mankind and desired a relationship. (John 3:16-17) Love is the underlying drive in most people.[How to reference and link to summary or text] The search for love seems endless within the human race, throughout the ages.[How to reference and link to summary or text] The Bible defines God as being the completeness of love. Love, as being defined by him, is demonstrated in his character and personality. Another way of defining this type of love is "godly love", a love shown through the example of Christ's sacrifice on the cross. However, this "sacrificial" love can also be expressed by humans.[How to reference and link to summary or text] For example, the love of a mother for her child. It is one one of the strongest bonds of love known to Man.[How to reference and link to summary or text] The mother would sacrifice anything for the child. It is this type of love that the Bible teaches us to follow and to share with one another. Love, in the end, is truly a sacrifice.[How to reference and link to summary or text]

Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of Christian Science, defines Love as one of 7 synonyms for God. This indicates that Diety is more than a being that has benevolent concerns for mankind, but rather that God is Love itself. Love is also synonymous with Principle, Mind, Soul, Spirit, Life, and Truth and indicate the depth and wholeness of Love.[How to reference and link to summary or text]

The Bhagavad Gita, India's ageless Hindu scripture, helps devotees to see that love conquers all. It says, "Sattva—pure, luminous, and free from sorrow—binds us to happiness and wisdom" (Number 6). Sattva, translated as purity, helps one to see that love evolves from selflessness.

Cultural views

- Main article: Love (cultural views)

The traditional Chinese character for love (愛) consists of a heart (心, in the middle) inside of "accept", "feel", or "perceive", which shows a graceful emotion.

Although there exist numerous cross-cultural unified similarities as to the nature and definition of love, as in there being a thread of commitment, tenderness, and passion common to all human existence, there are differences. This section is a stub. You can help by adding to it.

See also

|

Notes

- ↑ Oxford Illustrated American Dictionary (1998) + Merriam-Webster Collegiate Dictionary (2000)

- ↑ Kristeller, Paul Oskar (1980). Renaissance Thought and the Arts: Collected Essays, Princeton University.

- ↑ Mascaró, Juan (2003). The Bhagavad Gita, Penguin Classics. (J. Mascaró, translator)

- ↑ Kay, Paul (March 1984). What is the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis?. American Anthropologist 86 (1): pp. 65–79.

- ↑ Ancient Love Poetry.

- ↑ DiscoveryHealth Paraphilia. URL accessed on 2007-12-16.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Lewis, Thomas; Amini, F., & Lannon, R. (2000). A General Theory of Love, Random House.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Winston, Robert (2004). Human, Smithsonian Institution.

- ↑ Emanuele, E. (2005). Raised plasma nerve growth factor levels associated with early-stage romantic love. Psychoneuroendocrinology Sept. 05.

- ↑ Rubin, Zick (1970). Measurement of Romantic Love. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 16: 265–27.

- ↑ Rubin, Zick (1973). Liking and Loving: an invitation to social psychology, New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

- ↑ Berscheid, Ellen; Walster, Elaine, H. (1969). Interpersonal Attraction, Addison-Wesley Publishing Co. CCCN 69-17443.

- ↑ Peck, Scott (1978). The Road Less Traveled, Simon & Schuster.

- ↑ Fisher, Helen (2004). Why We Love – the Nature and Chemistry of Romantic Love, Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 0-8050-6913-5.

- ↑ Jammer, Max (1956). Concepts of Force, Dover Publications, Inc.. ISBN 0-486-40689-X.

- ↑ Bible, 8:6-7, NIV.

References

- Roger Allen, Hillar Kilpatrick, and Ed de Moor, eds. Love and Sexuality in Modern Arabic Literature. London: Saqi Books, 1995.

- Shadi Bartsch and Thomas Bartscherer, eds. Erotikon: Essays on Eros, Ancient and Modern. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

- Mary Baker Eddy, "Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures. 2006

- Ehrenberg, D. B. (2001). In the grip of passion: Love or addiction? On a specific kind of masochistic enthrallment. Lanham, MD: Jason Aronson.

- Helen Fisher. Why We Love: the Nature and Chemistry of Romantic Love

- Gabriele Froböse, Rolf Froböse, Michael Gross (Translator): Lust and Love: Is it more than Chemistry? Publisher: Royal Society of Chemistry, ISBN 0-85404-867-7, (2006).

- Johnson, P (2005) 'Love, Heterosexuality and Society'. Routledge: London.

- Thomas Jay Oord, Science of Love: The Wisdom of Well-Being. Philadelphia: Templeton Foundation Press, 2004.

- R. J. Sternberg. A triangular theory of love. 1986. Psychological Review, 93, 119–135

- R. J. Sternberg. Liking versus loving: A comparative evaluation of theories. 1987. Psychological Bulletin, 102, 331–345

- Sternberg, Robert (1998). Cupid's Arrow - the Course of Love through Time, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-47893-6.

- Dorothy Tennov. Love and Limerence: the Experience of Being in Love. New York: Stein and Day, 1979. ISBN 0-8128-6134-5

- Dorothy Tennov. A Scientist Looks at Romantic Love and Calls It "Limerence": The Collected Works of Dorothy Tennov. Greenwich, CT: The Great American Publishing Society (GRAMPS), [1]

- Wood, Wood and Boyd. The World of Psychology. 5th edition. 2005. Pearson Education, 402–403

- Jones, Del. "One of USA's Exports: Love, American Style" USA Today: February, 14, 2006.

Emotional states (list) |

|---|

|

Affection · Ambivalence · Anger · Angst · Annoyance · Anticipation · Anxiety · Apathy · Awe · Boredom · Calmness · Compassion · Confusion · Contempt · Contentment · Curiosity · Depression · Desire · Disappointment · Disgust · Doubt · Ecstasy · Embarrassment · Empathy · Emptiness · Enthusiasm · Envy · Epiphany · Euphoria · Fanaticism · Fear · Frustration · Gratification · Gratitude · Grief · Guilt · Happiness · Hatred · Homesickness · Hope · Hostility · Humiliation · Hysteria · Inspiration · Interest · Jealousy · Kindness · Limerence · Loneliness · Love · Lust · Melancholia · Nostalgia · Panic · Patience · Pity · Pride · Rage · Regret · Remorse · Repentance · Resentment · Righteous indignation · Sadness · Saudade · Schadenfreude · Sehnsucht · Self-pity · Shame · Shyness · Suffering · Surprise · Suspicion · Sympathy · Wonder · Worry |

|

See also: Meta-emotion |

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia (view authors). |