No edit summary |

m (→The Model: Fixed image size :)) |

||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

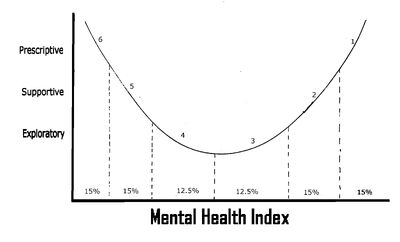

The model is represented in Figure 1, which has been christened both as “the Kiff curve” or “Joe’s smile” - take your pick. |

The model is represented in Figure 1, which has been christened both as “the Kiff curve” or “Joe’s smile” - take your pick. |

||

| − | [[Image:Fig 1.jpg]] |

+ | [[Image:Fig 1.jpg|thumb|400px|Figure 1: The Kiff Curve.]] |

On the y-axis I wanted to get away from the notion that the main therapeutic approaches are mutually exclusive and by then I felt that I was working in three main modes, which I characterised as: |

On the y-axis I wanted to get away from the notion that the main therapeutic approaches are mutually exclusive and by then I felt that I was working in three main modes, which I characterised as: |

||

| Line 53: | Line 53: | ||

===Group 6 – Long-term prescriptive cases=== |

===Group 6 – Long-term prescriptive cases=== |

||

There are clients whose capacity to relate is so impaired that they cannot easily profit from a supportive relationship alone, and their basic self care difficulties require the concrete structure of a directive approach. The very socially isolated son of a schizophrenic mother exemplifies this group. For much of his therapy he hardly seemed to engage meaningfully at all and we seemed to inhabit different worlds. It was only when we embarked on a programme of basic social skills training that he seemed to make significant progress. |

There are clients whose capacity to relate is so impaired that they cannot easily profit from a supportive relationship alone, and their basic self care difficulties require the concrete structure of a directive approach. The very socially isolated son of a schizophrenic mother exemplifies this group. For much of his therapy he hardly seemed to engage meaningfully at all and we seemed to inhabit different worlds. It was only when we embarked on a programme of basic social skills training that he seemed to make significant progress. |

||

| − | |||

==The Strengths of the Model== |

==The Strengths of the Model== |

||

Revision as of 20:35, 5 July 2006

Paper 1: Joe’s Smile: A model for thinking about clinical psychology

Joe Kiff, Dudley South PCT

Introduction

In this paper I want to introduce a integrative model that I have used for many years to understand what clinical psychologists do in adult mental health. In particular I seek to emphasis some historical trends that I believe have taken place in recent years that mean the bulk of our work now lies with complex, moderate to severe cases that pose difficult clinical challenges. In subsequent papers in this series I will argue that the current dominant theoretical model of CBT cannot inherently address these issues and that it is time for a thorough rethink of our professional allegiance to the scientist- practitioner model, the model of science upon which it is based, and the philosophical background to such a view of science.

I provided an early copy of this paper to Mowbray as part of my submission to the MAS review (Mowbray, 1989). Over the years many of my colleagues and supervisees have found it a useful framework for thinking about clinical issues and have urged me to update it.

The Model

In 1986, after I had been practising in Adult Mental Health for five years I consciously sat down to try to clarify what I knew. I had originally trained on the behaviourally orientated Birmingham course and had subsequently completed the certificate in psychodynamic therapy at the Tavistock clinic. I had also been a supervisor for the Lichfield counselling service for three years. By then I had personally seen a broad spectrum of approximately 250 people and I felt that I had a firm grasp of behavioural, counselling and psychotherapy techniques. The question at the forefront of my mind then was: what approach seemed relevant to which kind of client? Now with over 15,000 hours of direct clinical work and 3,000 hours as a supervisor I feel it provides a useful framework for thinking about clinical issues.

The model is represented in Figure 1, which has been christened both as “the Kiff curve” or “Joe’s smile” - take your pick.

Figure 1: The Kiff Curve.

On the y-axis I wanted to get away from the notion that the main therapeutic approaches are mutually exclusive and by then I felt that I was working in three main modes, which I characterised as:

1. Prescriptive

With some people I found that I primarily gave advice about practical courses of action. People were referred with a specific problem and the active ingredient of therapy was to help them make cognitive and behavioural changes to resolve the situation. CBT and psycho-educational models of working largely inform this work.

2. Supportive

Other people were referred with symptoms that seemed to reflect current conflicts in their lives. They were depressed and anxious because of social and relationship conundrums that they could not resolve. In these situations the active ingredient in the therapy involved providing them a safe environment within which they could clarify their options and values and come to the necessary emotional and practical decisions to improve their lives.

3. Exploratory

Other people were referred with problems that appeared to reflect long term patterns, based on their early life experiences. When the current difficulties could not be resolved at the supportive level the active ingredient in the therapy involved exploring the learning history.

Having ascertained the active ingredient of the therapy, I attempted to place each client along a continuum of ‘mental health’. An interesting pattern emerged when I plotted them against the ‘depth’ of my preferred therapy mode. When thinking about mental health I had observed a regularity amongst my patients. It seemed to me clear that in the majority of cases early life experiences frequently mirrored current social and relationship functioning and that this was related to the severity and complexity of peoples symptoms. I had combined these factors into a notional Mental Heath Index and felt that I could place people I had seen on a continuum.

At one end were people who seemed well integrated, able to relate to me as a therapist in a trusting and straightforward way. Generally speaking they appeared to come from stable family backgrounds, to have involved and satisfactory current social lives, usually with a stable partner, and were consulting with specific difficulties. At the other end were others who seemed to have tremendous difficulties relating to me, either because they were psychotic, or withdrawn, or too emotionally labile. Generally they had experienced very disturbed early lives, had very disturbed (or non existent) current relationships and had a whole plethora of problems. Placing people between these points I started to see what approach seemed to be effective for different clients. In making sense of this picture I identified six loose groupings that seemed to run into each other:

Group 1 – Short-term directive cases

These are well integrated people with specific problems. They are trusting and once a course of action was explained to them they are able to co-operate and generally benefit quickly from a symptomatic approach. At assessment there seemed be no justification for looking more deeply into their current relationships or further exploring their early life. An example of such a patient might be a young man involved in a road crash who had spent six months recovering in hospital. He was left with residual anxiety about driving and had lost social confidence, having been out of circulation for so long. His family and friends were supportive and anxiety management and social task setting were sufficient to help him.

Group 2 – Short-term supportive cases

For clients in this group counselling support is the main intervention. Take, for example, a woman who nursed her ageing mother for two years and was depressed at her death. With no evidence that the relationship between mother and daughter was particularly troubled, grief counselling was appropriate. There was no justification for exploring her early life and it would be insensitive to treat the depression as an isolated symptom. What was required was to provide the space in which grief could be explored, symptoms understood, and plans formulated for the future, on the basis of her own values. In this case the woman felt she had learnt a great deal about nursing old people and wanted a job in a care home. This gave her satisfaction and purpose and a basis on which to build a fresh life.

Group 3 – Short-term exploratory cases

As clients come from more disturbed backgrounds they are less able to resolve their current emotional difficulties without addressing their historical antecedents. For example, a woman who is having difficulties in her second marriage because she cannot trust her husband not to abandon her, perhaps needs to examine the idea that this was the issue behind her first divorce and appears to be related to the fact that her father left home unexpectedly when she was eight. In addition, the issue needs to be addressed in the transference with her male therapist who she has difficulty trusting. Assuming a reasonably integrated client, then short term exploratory therapy (e.g. Malan model) would seem appropriate.

Group 4 – Long-term exploratory cases

With more damaged clients, longer-term exploratory therapy might be indicated. For example, if the client had been the victim of physical violence when young and had a history of involvement with a sequence of men who beat her, then one might anticipate that therapy might be more difficult and time consuming. One is drawn into longer term work because the therapeutic issues are more complex, the problems brought more pervasive and resistant to change and the technical problem of maintaining the therapeutic relationship are more challenging.

Group 5 – Long-term supportive cases

For some clients the pain of working through the past is too much to bear, at least in the usual once a week context of NHS practice. For this group longer term, episodic supportive therapy is indicated to allow them to re-establish the status quo in their current lives and to come to terms with the chronicity of their difficulties. For example one client told of an extremely difficult childhood with his prostitute mother. Having six siblings all by different fathers it seemed the only reason he was not more disturbed was because his aunt had taken him away and provided a stable home when he was seven. When he came to therapy with crippling, wide spread social anxiety, his aunt was dying. I did not feel he was integrated enough to withstand an exploratory approach, but he related to me enough emotionally to benefit from a supportive relationship that took him through the crisis. People in this group are not generally cured of their condition but struggle with continuing difficulties. They are often re-referred at other times of crisis in their lives. I have come to see the value of offering intermittent time limited treatment contracts to such clients to provided support at particularly difficult times.

Group 6 – Long-term prescriptive cases

There are clients whose capacity to relate is so impaired that they cannot easily profit from a supportive relationship alone, and their basic self care difficulties require the concrete structure of a directive approach. The very socially isolated son of a schizophrenic mother exemplifies this group. For much of his therapy he hardly seemed to engage meaningfully at all and we seemed to inhabit different worlds. It was only when we embarked on a programme of basic social skills training that he seemed to make significant progress.

The Strengths of the Model

- For trainees faced with having to make sense of a number of approaches, particularly during the first year, the framework helps them see how the different models might be related.

- When supervising such trainees I tend to start them off with category 1 and 2 work, in order for them to gain confidence. Then, where the complexity emerges, I then look to develop their thinking from this base.

- The model integrates a number of theories into a coherent whole and illustrates integrationist working that I think reflects the way in which many of us work on a day to day basis.

- The model can help us understand the compatible roles of different professional groups within community mental health teams. Nurse Behaviour Therapists do mainly category 1 work, counsellors category 2, psychologists category 3 and 4, social workers and CPNs category 5 and 6.

- This underlines that the bread and butter work for psychologists in these contexts is with the moderate severity, moderate complexity patients whose problems reflect their social contexts and the patterns from their past.

- It is a model that illustrates level three working (Mowbray 1989) and managers have found this useful in conceptualising how psychologists contribute therapeutically across the whole spectrum of care and clarifying our central role in assessment and allocation.

- The model is a useful framework within which to consider the workload of an individual, service or department and to develop ideas for training, skill mix and experience levels for recruitment.

- The model accounts for a number of findings in the literature.

- Take 30% spontaneous remission rates. One can see how category 1 and 2 people could improve without treatment, having the necessary social and personal resources.

- It may help understand the finding that most treatments return success rates of 60%. For we would not expect category 5 and 6 people to improve substantially, at least within the timescales of most clinical trials.

- The model may give us some insight into why there is a broad agreement about the equal effectiveness of most treatments. On a straightforward basis we all give advice where appropriate, generally we can all be supportive and where we get stuck we tend to look for the patterns from the past whether we call them schema, scripts etc.

- One of the main strengths of the model for some colleagues has been the clarification of the limitations of therapy with category 5 and 6 people. Coming out of a training that uses a mastery model they really wrestle with finding a realistic level of therapeutic hope. Avoiding “interminable” therapy with these clients is the key to maintaining throughput and an important management focus minimising waiting lists.

- The model underlines the importance of psychologists equipping themselves with a broad range of skills and perspectives to be able to mix and match their theoretical and practical skills to the needs of the patient. This has implications for clinical training and the need to develop the capacity of learners to translate between different approaches.

- While the model was developed primarily in an Adult Mental Health setting psychologists in other specialties have found it helpful for thinking about their own work.

Historical Trends

Following recent NHS changes two important trends have emerged. Firstly, many of the more straightforward cases are no longer being referred into our CMHT system, being managed in primary care. From the pool of more complex cases remaining, the most complex of these are allocated to clinical psychologists, as most other CMHT staff do not have the training to deal with them effectively. Talking to colleagues this seems a common observation. Such referrals are more consistently challenging and there is a general feeling that our clinical training is too limited. The problem is not one of lack of inability to intellectually analyse peoples presenting symptoms and to develop a treatment plan per se. Rather the problem becomes an emotional one of managing our feelings in the sessions and maintaining our ability to think clearly in the face of confusing and contradictory presentations of the problem. In reflecting upon our experience we find we have moved away from conducting pure, literature-based interventions and find ourselves more reliant upon approaches that emerge from supervision (both giving and receiving it) the experience of personal therapy and accumulated life and clinical experience.

Conclusion

This picture of the current workload of clinical psychologists within community mental health teams indicates that our role is to treat complex, moderate to severe cases. These make particular demands on therapists that require us to modify our approach, and negotiate our way across the scientist practitioner/reflective practitioner boundary. In subsequent papers I want to examine this journey in more detail

References

Mowbray, D. Review of Clinical Psychology Services. 1989. MAS. Cheltenham.

Word count 2400