No edit summary |

m (fixing dead links) |

||

| (4 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{CompPsy}} |

{{CompPsy}} |

||

| − | {{Taxobox |

||

| − | | color = pink |

||

| − | | name = Hominids<ref name=MSW3>{{MSW3 Groves|pages=181-184}}</ref> |

||

| − | | image = Austrolopithecus africanus.jpg |

||

| − | | image_width = 250px |

||

| − | | image_caption = ''[[Australopithecus|Australopithecus africanus]]'' reconstruction |

||

| − | | regnum = [[Animal]]ia |

||

| − | | phylum = [[Chordata]] |

||

| − | | classis = [[Mammal]]ia |

||

| − | | ordo = [[Primate]]s |

||

| − | | subordo = [[Haplorrhini]] |

||

| − | | infraordo = [[Simiiformes]] |

||

| − | | parvordo = [[Catarrhini]] |

||

| − | | superfamilia = [[Hominoidea]] |

||

| − | | familia = '''Hominidae''' |

||

| − | | familia_authority = [[John Edward Gray|Gray]], [[1825]] |

||

| − | | subdivision_ranks = [[Genus|Genera]] |

||

| − | | subdivision = |

||

| − | *Subfamily [[Ponginae]] |

||

| − | **''[[Pongo]]'' - [[orangutan]]s |

||

| − | *Subfamily [[Homininae]] |

||

| − | **''[[Gorilla]]'' - [[gorilla]]s |

||

| − | **''[[chimpanzee|Pan]]'' - [[chimpanzee]]s |

||

| − | **''[[Homo (genus)|Homo]]'' - [[Human]]s |

||

| − | }} |

||

| − | __NOTOC__ |

||

| ⚫ | The '''hominids''' are the members of the |

||

| ⚫ | This classification has been |

||

| ⚫ | The '''hominids''' are the members of the biological family '''Hominidae''' (the '''great [[ape]]s'''), which includes [[human]]s, [[chimpanzee]]s, [[gorilla]]s, and [[orangutan]]s. <!--These are the common names for the four living genera in Hominidae. Please don't change it to include a mix of species and genera common names. See the classification below.--> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | |||

| ⚫ | This classification has been revised several times in the last few decades. Originally, the group was restricted to humans and their extinct relatives, with the other great apes being placed in a separate family, the '''Pongidae'''. This definition is still used by many [[anthropologist]]s and by lay people. However, that definition makes Pongidae paraphyletic, whereas most taxonomists nowadays encourage monophyletic groups. Thus many biologists consider Hominidae to include Pongidae as the subfamily Ponginae, or restrict the latter to the orangutans and their extinct relatives like ''Gigantopithecus''. The taxonomy shown here follows the monophyletic groupings. |

||

| + | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| − | Many extinct hominids have been studied to help understand the relationship between modern humans and the other extant hominids. Some of the extinct members of this family include ''Gigantopithecus'', '' |

+ | Many extinct hominids have been studied to help understand the relationship between modern humans and the other extant hominids. Some of the extinct members of this family include ''Gigantopithecus'', ''Orrorin'', ''Ardipithecus'', ''Kenyanthropus'', and the australopithecines ''Australopithecus'' and ''Paranthropus''. |

The exact criteria for membership in the Homininae are not clear, but the subfamily generally includes those [[species]] which share more than 97% of their [[DNA]] with the modern human [[genome]], and exhibit a capacity for [[language]] and for simple [[culture]]s beyond the family or band. The [[theory of mind]] including such faculties as mental state attribution, empathy and even empathetic deception is a controversial criterion distinguishing the adult human alone among the hominids. Humans acquire this capacity at about four and a half years of age, whereas it has neither been proven nor disproven that gorillas and chimpanzees develop a theory of mind.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Heyes, C. M. | year = 1998 | title = THEORY OF MIND IN NONHUMAN PRIMATES | journal = Behavioral and Brain Sciences | id = bbs00000546 | url = http://www.bbsonline.org/documents/a/00/00/05/46/index.html}}</ref> This is also the case for some [[new world monkey]]s outside the family of great apes, as, for example, the [[Capuchin_monkey#Theory_of_mind|capuchin monkeys]]. |

The exact criteria for membership in the Homininae are not clear, but the subfamily generally includes those [[species]] which share more than 97% of their [[DNA]] with the modern human [[genome]], and exhibit a capacity for [[language]] and for simple [[culture]]s beyond the family or band. The [[theory of mind]] including such faculties as mental state attribution, empathy and even empathetic deception is a controversial criterion distinguishing the adult human alone among the hominids. Humans acquire this capacity at about four and a half years of age, whereas it has neither been proven nor disproven that gorillas and chimpanzees develop a theory of mind.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Heyes, C. M. | year = 1998 | title = THEORY OF MIND IN NONHUMAN PRIMATES | journal = Behavioral and Brain Sciences | id = bbs00000546 | url = http://www.bbsonline.org/documents/a/00/00/05/46/index.html}}</ref> This is also the case for some [[new world monkey]]s outside the family of great apes, as, for example, the [[Capuchin_monkey#Theory_of_mind|capuchin monkeys]]. |

||

| − | However, without the ability to test whether early members of the Homininae (such as '' |

+ | However, without the ability to test whether early members of the Homininae (such as ''Homo erectus'', ''Homo neanderthalensis'', or even the australopithecines) had a theory of mind, it is difficult to ignore similarities seen in their living cousins. Despite an apparent lack of real culture and significant physiological and psychological differences, some say that the orangutan may also satisfy these criteria. These scientific debates take on political significance for advocates of [[Great Ape personhood]]. |

| − | In [[2002]], a 6–7 million year old |

+ | In [[2002]], a 6–7 million year old fossil skull nicknamed "Toumaï" by its discoverers, and formally classified as ''Sahelanthropus tchadensis'', was discovered in Chad and is possibly the earliest hominid fossil ever found. In addition to its age, Toumaï, unlike the 3–4 million year younger gracile australopithecine dubbed "Lucy", has a relatively flat face without the prominent snout seen on other pre-''Homo'' hominids. Some researchers have made the suggestion that this previously unknown species may in fact be a direct ancestor of modern humans (or at least closely related to a direct ancestor). Others contend that one fossil is not enough to make such a claim because it would overturn the conclusions of over 100 years of [[anthropology|anthropological]] study. A report on this finding was published in the journal ''[[Nature (journal)|Nature]]'' on July 11, [[2002]]. While some scientists claim that it is merely the skull of a female gorilla, others have called it the most important hominin fossil since ''Australopithecus''. |

| − | In addition to the Tourmai fossil, US genome experts believe that the species associated with the chimpanzees and proto-humans split interbred over a long period of time, swapping genes, before making a final separation. A paper, whose authors include |

+ | In addition to the Tourmai fossil, US genome experts believe that the species associated with the chimpanzees and proto-humans split interbred over a long period of time, swapping genes, before making a final separation. A paper, whose authors include David Reich and Eric Lander (Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)), was published in journal ''[[Nature (journal)|Nature]]'' in May 2006. |

It is generally believed that the ''Pan/Homo'' split occurred about 6.5–7.4 million years ago, but the [[molecular clock]] (a method of calculating evolution based on the speed at which genes mutate) suggests the genera split 5.4–6.3 million years ago. Previous studies looked at average genetic differences between human and chimp. The new study compares the ages of key sequences of genes of modern humans and modern chimps. Some sequences are younger than others, indicating that chimps and humans gradually split apart over a period of 4 million years. The youngest human chromosome is the X sex chromosome which is about 1.2 million years more recent than the 22 autosomes. The X chromosome is known to be vulnerable to selective pressure. Its age suggests there was an initial split between the two species, followed by gradual divergence and interbreeding that resulted in younger genes, and then a final separation. |

It is generally believed that the ''Pan/Homo'' split occurred about 6.5–7.4 million years ago, but the [[molecular clock]] (a method of calculating evolution based on the speed at which genes mutate) suggests the genera split 5.4–6.3 million years ago. Previous studies looked at average genetic differences between human and chimp. The new study compares the ages of key sequences of genes of modern humans and modern chimps. Some sequences are younger than others, indicating that chimps and humans gradually split apart over a period of 4 million years. The youngest human chromosome is the X sex chromosome which is about 1.2 million years more recent than the 22 autosomes. The X chromosome is known to be vulnerable to selective pressure. Its age suggests there was an initial split between the two species, followed by gradual divergence and interbreeding that resulted in younger genes, and then a final separation. |

||

| Line 116: | Line 92: | ||

== External links == |

== External links == |

||

*[http://www.unep.org/grasp/Resources/index.asp Additional information on great apes] |

*[http://www.unep.org/grasp/Resources/index.asp Additional information on great apes] |

||

| − | *[http://www.npr.org/programs/atc/features/2002/july/toumai/index.html NPR News: Toumaï the Human Ancestor] |

+ | *[http://web.archive.org/web/20020805134540/http://www.npr.org/programs/atc/features/2002/july/toumai/index.html NPR News: Toumaï the Human Ancestor] |

*[http://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/homs/species.html Hominid Species] at talkorigins.org |

*[http://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/homs/species.html Hominid Species] at talkorigins.org |

||

*[http://www.modernhumanorigins.net/ For more details on Hominid species, including excellent photos of fossil hominids] |

*[http://www.modernhumanorigins.net/ For more details on Hominid species, including excellent photos of fossil hominids] |

||

Revision as of 12:45, 11 August 2014

Assessment |

Biopsychology |

Comparative |

Cognitive |

Developmental |

Language |

Individual differences |

Personality |

Philosophy |

Social |

Methods |

Statistics |

Clinical |

Educational |

Industrial |

Professional items |

World psychology |

Animals · Animal ethology · Comparative psychology · Animal models · Outline · Index

The hominids are the members of the biological family Hominidae (the great apes), which includes humans, chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans.

This classification has been revised several times in the last few decades. Originally, the group was restricted to humans and their extinct relatives, with the other great apes being placed in a separate family, the Pongidae. This definition is still used by many anthropologists and by lay people. However, that definition makes Pongidae paraphyletic, whereas most taxonomists nowadays encourage monophyletic groups. Thus many biologists consider Hominidae to include Pongidae as the subfamily Ponginae, or restrict the latter to the orangutans and their extinct relatives like Gigantopithecus. The taxonomy shown here follows the monophyletic groupings.

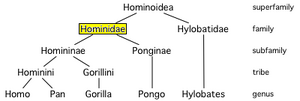

Especially close human relatives form a subfamily, the Homininae. Some researchers go so far as to include chimpanzees and gorillas in the genus Homo along with humans, but more commonly accepted to describe the relationships as shown here.

Many extinct hominids have been studied to help understand the relationship between modern humans and the other extant hominids. Some of the extinct members of this family include Gigantopithecus, Orrorin, Ardipithecus, Kenyanthropus, and the australopithecines Australopithecus and Paranthropus.

The exact criteria for membership in the Homininae are not clear, but the subfamily generally includes those species which share more than 97% of their DNA with the modern human genome, and exhibit a capacity for language and for simple cultures beyond the family or band. The theory of mind including such faculties as mental state attribution, empathy and even empathetic deception is a controversial criterion distinguishing the adult human alone among the hominids. Humans acquire this capacity at about four and a half years of age, whereas it has neither been proven nor disproven that gorillas and chimpanzees develop a theory of mind.[1] This is also the case for some new world monkeys outside the family of great apes, as, for example, the capuchin monkeys.

However, without the ability to test whether early members of the Homininae (such as Homo erectus, Homo neanderthalensis, or even the australopithecines) had a theory of mind, it is difficult to ignore similarities seen in their living cousins. Despite an apparent lack of real culture and significant physiological and psychological differences, some say that the orangutan may also satisfy these criteria. These scientific debates take on political significance for advocates of Great Ape personhood.

In 2002, a 6–7 million year old fossil skull nicknamed "Toumaï" by its discoverers, and formally classified as Sahelanthropus tchadensis, was discovered in Chad and is possibly the earliest hominid fossil ever found. In addition to its age, Toumaï, unlike the 3–4 million year younger gracile australopithecine dubbed "Lucy", has a relatively flat face without the prominent snout seen on other pre-Homo hominids. Some researchers have made the suggestion that this previously unknown species may in fact be a direct ancestor of modern humans (or at least closely related to a direct ancestor). Others contend that one fossil is not enough to make such a claim because it would overturn the conclusions of over 100 years of anthropological study. A report on this finding was published in the journal Nature on July 11, 2002. While some scientists claim that it is merely the skull of a female gorilla, others have called it the most important hominin fossil since Australopithecus.

In addition to the Tourmai fossil, US genome experts believe that the species associated with the chimpanzees and proto-humans split interbred over a long period of time, swapping genes, before making a final separation. A paper, whose authors include David Reich and Eric Lander (Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)), was published in journal Nature in May 2006.

It is generally believed that the Pan/Homo split occurred about 6.5–7.4 million years ago, but the molecular clock (a method of calculating evolution based on the speed at which genes mutate) suggests the genera split 5.4–6.3 million years ago. Previous studies looked at average genetic differences between human and chimp. The new study compares the ages of key sequences of genes of modern humans and modern chimps. Some sequences are younger than others, indicating that chimps and humans gradually split apart over a period of 4 million years. The youngest human chromosome is the X sex chromosome which is about 1.2 million years more recent than the 22 autosomes. The X chromosome is known to be vulnerable to selective pressure. Its age suggests there was an initial split between the two species, followed by gradual divergence and interbreeding that resulted in younger genes, and then a final separation.

Classification

Hominoid family tree

Skulls of an orangutan and a gorilla

- Family Hominidae: humans and other great apes; extinct genera and species excluded.[2]

- Subfamily Ponginae

- Genus Pongo

- Bornean Orangutan, Pongo pygmaeus

- Pongo pygmaeus pygmaeus

- Pongo pygmaeus morio

- Pongo pygmaeus wurmbii

- Sumatran Orangutan, Pongo abelii

- Bornean Orangutan, Pongo pygmaeus

- Genus Pongo

- Subfamily Homininae

- Tribe Gorillini

- Genus Gorilla

- Western Gorilla, Gorilla gorilla

- Western Lowland Gorilla, Gorilla gorilla gorilla

- Cross River Gorilla, Gorilla gorilla diehli

- Eastern Gorilla, Gorilla beringei

- Mountain Gorilla, Gorilla beringei beringei

- Eastern Lowland Gorilla, Gorilla beringei graueri

- Western Gorilla, Gorilla gorilla

- Genus Gorilla

- Tribe Hominini

- Genus Pan

- Common Chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes

- Central Chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes troglodytes

- West African Chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes verus

- Nigerian Chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes vellerosus

- Eastern Chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii

- Bonobo (Pygmy Chimpanzee), Pan paniscus

- Common Chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes

- Genus Homo

- Human, Homo sapiens sapiens

- Genus Pan

- Tribe Gorillini

- Subfamily Ponginae

In addition to the extant species and subspecies above, archaeologists, paleontologists, and anthropologists have discovered numerous extinct species. The list below are some of the genera of those discoveries.

- Subfamily Ponginae

- Gigantopithecus†

- Sivapithecus†

- Lufengpithecus†

- Ankarapithecus†

- Ouranopithecus†

- Subfamily Homininae

See also

.

- Kinshasa Declaration on Great Apes

- Ape extinction

- Declaration on Great Apes

- Evolution of Homo sapiens

- Evolutionary neuroscience

- Graphical timeline of human evolution

- Great ape language

- Great Ape Project

- List of apes - notable individual apes

- The Mind of an Ape

- Great Ape research ban

- Great Apes Survival Project

References

- ↑ Heyes, C. M. (1998). THEORY OF MIND IN NONHUMAN PRIMATES. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. bbs00000546.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedMSW3

External links

- Additional information on great apes

- NPR News: Toumaï the Human Ancestor

- Hominid Species at talkorigins.org

- For more details on Hominid species, including excellent photos of fossil hominids

- Scientific American Magazine (April 2006 Issue) Why Are Some Animals So Smart?

Extant primate families by suborder | |

|---|---|

| Strepsirrhini |

Cheirogaleidae · Lemuridae · Lepilemuridae · Indriidae · Daubentoniidae · Lorisidae · Galagidae |

| Haplorrhini |

Tarsiidae · Cebidae · Aotidae · Pitheciidae · Atelidae · Cercopithecidae · Hylobatidae · Hominidae |

ar:أسلاف الإنسان ca:Hominidae da:Menneskeabe (Hominidae) de:Menschenaffen es:Hominidae eo:Homedoj fr:Hominidae hu:Hominidák ko:사람과 he:הומינידים la:Hominidae lt:Hominidai li:Minsape nl:Hominidae lb:Mënschenafen pt:Hominidae ru:Гоминиды fi:Ihmisapinat sv:Människoapor vi:Họ Người zh:人科

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia (view authors). |