No edit summary |

m (fixing dead links) |

||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

The market expansion for marijuana in Europe is also happening because dealers in certain countries offer extremely adulterated hash almost exclusively{{Fact|date=February 2007}}. Marijuana is more difficult to adulterate, although some dealers attempt to modify it as well, usually with less success than with hash. Some young European consumers have become so accustomed to impure hashish that they erroneously believe it is the only quality available. |

The market expansion for marijuana in Europe is also happening because dealers in certain countries offer extremely adulterated hash almost exclusively{{Fact|date=February 2007}}. Marijuana is more difficult to adulterate, although some dealers attempt to modify it as well, usually with less success than with hash. Some young European consumers have become so accustomed to impure hashish that they erroneously believe it is the only quality available. |

||

| − | Morocco's hash product is exported almost entirely to Europe, [[Algeria]] and [[Tunisia]], with only a small fraction seeming to reach the [[United States]] <ref>[http://www.state.gov/p/inl/rls/nrcrpt/2005/vol1/html/42369.htm International Narcotics Control Strategy Report], released by the Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, March 2005</ref>. About 80% of the hashish seized in [[France]] every year comes from Morocco. |

+ | Morocco's hash product is exported almost entirely to Europe, [[Algeria]] and [[Tunisia]], with only a small fraction seeming to reach the [[United States]] <ref>[http://web.archive.org/web/20050822013434/http://www.state.gov/p/inl/rls/nrcrpt/2005/vol1/html/42369.htm International Narcotics Control Strategy Report], released by the Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, March 2005</ref>. About 80% of the hashish seized in [[France]] every year comes from Morocco. |

In France and the German- and French-speaking parts of Switzerland, this is known as ''Maroc'' (''Maroc'' meaning ''Morocco'' in French). In [[Spain]] it is called ''Costo'', and ''Chocolate''. In the United Kingdom, it is variously known as ''brown (also a name for heroin in some parts of the UK),'' ''hash,'' ''resin'', ''puff'', ''blow'', ''soap bar'', ''solid'', and ''block.'' In the Netherlands, this is called ''Maroc'', ''Lieb'' (Lebanon) or, from ''quality zero'' being best to ''secundeira'' being worst: ''triple zero'', ''zero zero'', ''super primaira'', ''primaira'', ''secundeira''. Also, there is a branch of nearly white ''powder hash'' (''pollen'' or ''kief has'') that is the result of not stamping the raw material for the more common compressed hashish. |

In France and the German- and French-speaking parts of Switzerland, this is known as ''Maroc'' (''Maroc'' meaning ''Morocco'' in French). In [[Spain]] it is called ''Costo'', and ''Chocolate''. In the United Kingdom, it is variously known as ''brown (also a name for heroin in some parts of the UK),'' ''hash,'' ''resin'', ''puff'', ''blow'', ''soap bar'', ''solid'', and ''block.'' In the Netherlands, this is called ''Maroc'', ''Lieb'' (Lebanon) or, from ''quality zero'' being best to ''secundeira'' being worst: ''triple zero'', ''zero zero'', ''super primaira'', ''primaira'', ''secundeira''. Also, there is a branch of nearly white ''powder hash'' (''pollen'' or ''kief has'') that is the result of not stamping the raw material for the more common compressed hashish. |

||

Revision as of 16:04, 16 August 2014

Assessment |

Biopsychology |

Comparative |

Cognitive |

Developmental |

Language |

Individual differences |

Personality |

Philosophy |

Social |

Methods |

Statistics |

Clinical |

Educational |

Industrial |

Professional items |

World psychology |

Biological: Behavioural genetics · Evolutionary psychology · Neuroanatomy · Neurochemistry · Neuroendocrinology · Neuroscience · Psychoneuroimmunology · Physiological Psychology · Psychopharmacology (Index, Outline)

Confiscated hashish from the United States Drug Enforcement Administration.

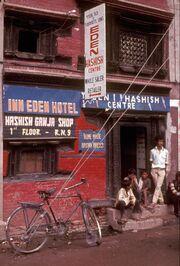

Hashish (from Arabic: حشيش ḥashīsh, lit. grass; also hash or many slang terms) is a preparation of Cannabis composed of the compressed trichomes collected from the Cannabis plant. It contains the same active ingredients as Cannabis (but in higher concentrations) and produces the same psychoactive effects[How to reference and link to summary or text]. Laws which apply to Cannabis usually also apply to hashish[How to reference and link to summary or text].

Hashish is solid, of varying hardness and pliability, softening under heat. Its colour can vary from reddish brown to black or it can be golden coloured or greenish if it contains surplus plant material. It is consumed in much the same way as Cannabis buds, often being smoked in joints mixed with tobacco or Cannabis buds, or in smoking pipes, or vapourized. It can also be eaten or used as an ingredient of food (typically cookies, cakes or brownies).

History

It is believed that hash first originated from Central Asia, as this region was among the first to be populated by the Cannabis plant, which may have originated in the Himalayas[How to reference and link to summary or text]. Traditionally C. sativa subsp. indica has been cultivated for production of hashish[How to reference and link to summary or text].

Hash quickly spread around the world after the Arabs began to gather and trade it[How to reference and link to summary or text]. Production of hash later spread to North Africa (most prominently Morocco) and the Middle East (Lebanon) and then South Asia (mostly in India and Pakistan).

Consumption of hashish saw a dramatic increase in the 20th century, becoming a popular pastime in Europe and America, gaining prominence in the hippie scene[How to reference and link to summary or text]. Hashish levels declined significantly in the United States starting in the 1980s for several reasons, including the Soviet war in Afghanistan. Mostly the decline was due to a huge jump in price and quality of imported marijuana [How to reference and link to summary or text]. This helped increase the popularity of marijuana use in North America, and encouraged new growing methods such as growing marijuana indoors[How to reference and link to summary or text].

Manufacturing processes

The Capitate-Stalked trichomes of the Cannabis plant.

Hash is made from tetrahydrocannabinol-rich glandular hairs known as trichomes, as well as varying amounts of Cannabis flower and leaf fragments. The flowers of a mature female plant contain the most trichomes, though trichomes also occur on other parts of the plant. Certain strains of Cannabis are cultivated specifically for their ability to produce large quantities of trichomes, and are thus called hash plants.

The resin reservoirs of the trichomes (sometimes erroneously called pollen) are separated from the plant via various methods. The resulting concentrate is formed into blocks of hashish, which can be easily stored and transported. Alternatively, the powder consisting of uncompressed, dry trichomes is often referred to as kief instead of hashish.

Mechanical separation methods use physical action to remove the trichomes from the plant. Sieving over a fine screen is a vital part of most methods. The plants may be sifted by hand or in motorized tumblers. Hash made in this way is sometimes called dry sift. Finger hash is produced by rolling the ripe trichome-covered flowers of the plant between the fingers and collecting the resin that sticks to the fingers. It is a highly labour intensive process which produces spherical balls of resin. Trichomes and resins can also be collected passively through cleaning of scissors that have been used to cut the plant, or containers like a kief-box used to store it.

Ice water separation is a more modern mechanical separation method which submerges the plant in ice and water and stirs the mixture. Trichomes are broken off the plant as the ice moves, while the low temperature make the trichomes more brittle so they break off easily. The waste plant matter, detached trichomes, and water are separated by filtering through a series of increasingly fine screens. Kits are commercially available which provide a series of filter screens meant to fit inside standard bucket sizes. Hash made in this way is sometimes called ice hash, or bubble hash.

Chemical separation methods generally use a solvent to dissolve the desirable resins in the plant while not dissolving undesirable components. The solid plant material is then filtered out of the solution and discarded. The solvent may then be evaporated, leaving behind the desirable resins. As THC is fat-soluble, it is also possible to dissolve hashish in butter and use it for cooking (see hash cookies and Alice B. Toklas brownies). The product of chemical separations is more commonly referred to as honey oil, hash oil, or just oil.

Quality

The main factors affecting quality are potency and purity. Different Cannabis plants will produce resins with unique chemical profiles which vary in potency. The manufacturing process may to some degree introduce less desirable materials such as tiny pieces of leaf matter or even purposefully added adulterants; these reduce the purity of the hash.

Pure, properly stored hashish of premium quality is soft and can be moulded by the heat of the fingers alone[How to reference and link to summary or text]. Old, improperly stored hashish of poor quality is rock-hard and brittle, and has to be heated substantially before it is soft enough for use (although some hashish of considerable potency, usually Moroccan, may also be found in hard form)[How to reference and link to summary or text]. Most hashish falls in between these two extremes, and the tactile qualities also vary according to the methods used in extraction and pressing. There is also hashish of greenish or reddish hue. A green tinge may indicate that the hashish is impure, which has been cut with low-quality leaf or contains high quantities of chlorophyll.

Low quality forms of hash often contain adulterants used as cutting agents added to exaggerate the value of hash through increasing the volume or including other cheaper drugs.[How to reference and link to summary or text] Such forms usually possess a low potency and may have a strangeness in taste and feel. The adulterants in the hash may range from waste material from the Cannabis plant to products such as soap, vaseline, beeswax, boot polish, licorice, henna, ground coffee, milk powder, pine resin, barbiturates, ketamine, aspirin, glues and dyes, as well as carcinogenic solvents such as toluene and benzene.[How to reference and link to summary or text] The low quality may lead one to smoke more to get the same effect.

Because hashish, particularly in Northern Europe, is often adulterated, some people have started boiling their hash in water for a few minutes and then drying it before smoking. This is thought to remove all water-soluble adulterants while the psychoactive cannabinols remain intact as the temperature isn't sufficient to destroy them and they aren't soluble in water.[How to reference and link to summary or text]

Hash by Region

Production

Hashish is traditionally produced in desert conditions and is almost never cultivated in the tropics. It is traditionally found in a belt extending from North Africa to North India and into Central Asia [How to reference and link to summary or text]. The primary hash-producing countries are Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nepal, Morocco, Egypt, and India[How to reference and link to summary or text].

Charas and gardaa are the primary products. Much of the hash available is high quality, although some adulterated product is available, easily identifiable by its relatively low prices. Charas, a substance which is hand-rubbed directly from the Cannabis plant, is generally produced in Nepal and India. Users report that charas generally produces a more trippy, "up" high due to the plants being mostly Sativa[How to reference and link to summary or text]. Pollen or "blonde hash", often from Morocco and the Netherlands, tends to produce both cerebral and narcotic highs, depending on the Cannabis strain used to produce it[How to reference and link to summary or text].

A visitor to the Rif mountains and the town of Ketama in Morocco in Dec 1976 described the production of hashish. Workers rubbed the leaves of the Cannabis plant over fine muslin fabric. When 100 grams of the powder was collected it was then wrapped in more fine muslin, put onto a heated metal plate, and rolled down with a bottle. This process produced a slightly sticky solid brown mass in the form of a square slab, around half the size of a paper-back book and about 1/2 centimetre thick. This block would be wrapped in cellophane. Only genuine top-quality hashish carried the imprint of the muslin on the surface of the block.[How to reference and link to summary or text]

In Afghanistan there is a method of making hash which resembles charas. First, Cannabis resin is placed on a large heated mortar, then the resin is threshed with a heavy object. The result is a very gooey, sticky black hash. This method is mostly used in villages around the Hindu Kush mountain region[How to reference and link to summary or text].

Hash is also produced now in the deserts of Northern Mexico however the demand for it and thus amount produced is insignificant compared to that for fresh Mexican marijuana, especially into the lucrative United States markets[How to reference and link to summary or text].

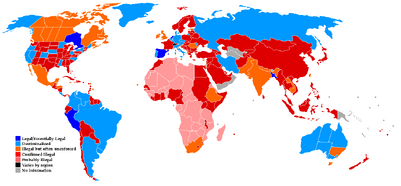

Consumption

World laws on cannabis possession (small amount). Data is from multiple sources detailed on the full source list. This map is a work in progress, please give corrections and additions here.

Hashish is more widely available in Europe, North Africa and parts of Asia than elsewhere. Reasons for its use in Europe include the fact that hashish is much more compact and thus easier to smuggle than marijuana, and also simply that the producing countries are much closer to Europe than to other developed world markets (where the price is much higher than in the developing world) and have a long tradition of making hashish for storage and export.

The market expansion for marijuana in Europe is also happening because dealers in certain countries offer extremely adulterated hash almost exclusively[How to reference and link to summary or text]. Marijuana is more difficult to adulterate, although some dealers attempt to modify it as well, usually with less success than with hash. Some young European consumers have become so accustomed to impure hashish that they erroneously believe it is the only quality available.

Morocco's hash product is exported almost entirely to Europe, Algeria and Tunisia, with only a small fraction seeming to reach the United States [1]. About 80% of the hashish seized in France every year comes from Morocco.

In France and the German- and French-speaking parts of Switzerland, this is known as Maroc (Maroc meaning Morocco in French). In Spain it is called Costo, and Chocolate. In the United Kingdom, it is variously known as brown (also a name for heroin in some parts of the UK), hash, resin, puff, blow, soap bar, solid, and block. In the Netherlands, this is called Maroc, Lieb (Lebanon) or, from quality zero being best to secundeira being worst: triple zero, zero zero, super primaira, primaira, secundeira. Also, there is a branch of nearly white powder hash (pollen or kief has) that is the result of not stamping the raw material for the more common compressed hashish.

Soft hash that is usually very dark brown to black in colour goes under the name black in France, squidgey or soft black (named due to the colour and properties of the hash) in the UK, or Paki Black in Spain (meaning it originates from Pakistan). Soft, dark hash is in the Netherlands normally referred to as Afghan. Also popular brands are Citral and Fungus in Kashmir.

Hash is far less popular in the United States than in Europe. Though hashish use is experiencing a resurgence in parts of North America (especially the Pacific Northwest) with the popularity and commercial availability of ice-water extraction kits[How to reference and link to summary or text].

Preparation and methods of use

Like ordinary Cannabis preparations, hashish is usually smoked, though it can also be eaten or vapourized.

Hash is often crumbled into tiny pieces or formed into shapes to obtain maximum surface area when burning. Hash can be smoked in most implements used for cannabis smoking, sometimes a pipe screen is used. Often hash is mixed with tobacco, Cannabis, or another herb. Heat may be used to bond the hash to the other smokeable substance. This mixture can be rolled up into a cigarette or smoked in a pipe.

A piece of hash may be ignited by cigarette coals or other means and placed inside a container. The smoke that collects inside can then be inhaled. Dabous or Khabour (stick in Arabic) is a North African technique. Bottle tokes is a similar method found in Canada and also in Russia.

Hash can be placed on very hot pieces of metal and the resulting smoke inhaled. Hot knives is a method that involves heating up knives on a stove and then crushing a little ball of the hash between them and inhaling the released smoke with a straw. Hash cones is a method where a piece of hash is attached to metal wire and then heated.

Honey oil

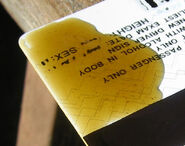

Golden cannabis oil on a card

Honey oil (often shortened to oil, and sometimes referred to as BHO, or butane hash oil, which is particular to the method by which it is made) is an essential oil that has a viscosity ranging from thick to runny, extracted from the cannabis plant. It is commonly smoked using hot metal blades or plates, inhaled using specially designed vaporizers, or smoked from a bed of ashes. Honey oil is considerably more potent than cannabis itself, due to its extreme purity and lack of other vegetative matter.

A closeup image of a drop of cannabis oil on the end of a needle

Honey oil is a psychoactive drug in the same class as cannabis, from which it is derived, and contains a similar blend of THC, cannabidinoids, and cannibidinols (in the UK, cannabis and hashish are class C while cannabis oil is class A). The THC content of honey oil is variable based on the particular strain of cannabis from which it was derived, and is similar to that of hashish. The name honey refers to the colour and consistency of the oil, there is not actual honey involved.

Manufacturing

Honey oil is made by separating the resins of a cannabis plant from the plant material, using one of a number of industrial solvents, such as butane, hexane, grain alcohol and denatured alcohol, naphtha, and various mixtures of these chemicals. Solvents are selected based on their ability to evaporate completely and cleanly, leaving no chemical residue, as well as which substances they more readily dissolve.

The purest, most potent grades of honey oil are made using only the flowers and leaves of the female cannabis plant which contain trichomes. This material is placed in a metal or plastic sleeve and washed in chemical solvents to separate the resin from the plant material. The solvent slurry is optionally filtered, then reduced by evaporation, resulting in paste that varies in colour from amber to dark green. This paste if filtered will be translucent and runny. If the paste is not filtered, it may by very thick, and opaque.

The most common solvent used in the preparation of honey oil is high-grade butane, sold in sporting goods stores and used in camping stoves and cigarette lighters. Due to the low boiling point and extreme combustibility of butane, extreme care is needed in the handling and preparation of these materials.

Honey oil made using isopropyl alcohol is referred to as ISO Oil or as QWISO for Quick Wash ISO and is quickly replacing butane as the most common solvent for making Honey Oil. Isopropyl alcohol [1] is safer than butane [2].

Availability

Honey oil is generally considered the province of amateur growers[How to reference and link to summary or text], who make it from collected trim leaves and immature "buds" from harvests as a by-product. Honey oil is generally not sold on the street as commonly as other cannabis products[How to reference and link to summary or text], but is highly prized among connoisseurs and those who use cannabis products medicinally.

Honey is most often found in rural areas where fresh marijuana is not available all year round[How to reference and link to summary or text]. A high prevalence of 'outdoor' marijuana growers will make oil to use or sell through the winter months when there is no crop.

See also

References

- ↑ International Narcotics Control Strategy Report, released by the Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, March 2005

Further reading

- Abel, E. L. (2005). Jacques Joseph Moreau (1804-1884): American Journal of Psychiatry Vol 162(3) Mar 2005, 458.

- Amit, Z., Corcoran, M. E., Charness, M. E., & Shizgal, P. (1973). Intake of diazepam and hashish by alcohol preferring rats deprived of alcohol: Physiology & Behavior Vol 10(3) Mar 1973, 523-527.

- Aziz, S., & Shah, A. (1995). Home environment and peer relations of addicted and nonaddicted university students: Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied Vol 129(3) May 1995, 277-284.

- Bahri, T., & Amir, T. (1994). Effect of hashish on vigilance performance: Perceptual and Motor Skills Vol 78(1) Feb 1994, 11-16.

- Bell, J. (1985). On the Haschisch or Cannabis Indica: Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment Vol 2(4) 1985, 239-243.

- Benjamin, W. (2006). On hashish. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press/Harvard University Press.

- Bollotte, G. (1973). Moreau de Tours: 1804-1884: Confrontations Psychiatriques Vol 6(11) 1973, 9-26.

- Brook, U. (1993). High school pupils' attitude and experience with drugs in Holon, Israel: International Journal of the Addictions Vol 28(7) May 1993, 667-676.

- Cami, J., Guerra, D., Ugena, B., Segura, J., & et al. (1991). Effect of subject expectancy on the THC intoxication and disposition from smoked hashish cigarettes: Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior Vol 40(1) Sep 1991, 115-119.

- Coombs, R. H., Fawzy, F. I., & Gerber, B. E. (1984). Patterns of substance use among children and youth: A longitudinal study: Substance & Alcohol Actions/Misuse Vol 5(1) 1984, 59-67.

- Coombs, R. H., Fawzy, F. I., & Gerber, B. E. (1986). Patterns of cigarette, alcohol, and other drug use among children and adolescents: A longitudinal study: International Journal of the Addictions Vol 21(8) 1986, 897-913.

- Corcoran, M. E. (1972). Self-administration of cannabis by rats: Dissertation Abstracts International Vol.

- Corcoran, M. E. (1973). Role of drug novelty and metabolism in the aversive effects of hashish injections in rats: Life Sciences Vol 12(2, Pt 1) Jan 1973, 63-72.

- Corcoran, M. E., & Amit, Z. (1974). Reluctance of rats to drink hashish suspensions: Free-choice and forced consumption, and the effects of hypothalamic stimulation: Psychopharmacologia Vol 35(2) 1974, 129-147.

- Dembo, R., Williams, L., Schmeidler, J., & Wothke, W. (1993). A longitudinal study of the predictors of the adverse effects of alcohol and marijuana/hashish use among a cohort of high risk youths: International Journal of the Addictions Vol 28(11) Sep 1993, 1045-1083.

- Dembo, R., Williams, L., Wothke, W., & Schmeidler, J. (1992). Examining a structural model of the relationships among alcohol use, marijuana/hashish use, their effects, and emotional and psychological problems over time in a cohort of high-risk youths: Deviant Behavior Vol 13(2) Apr-Jun 1992, 185-215.

- Duncan, D. F. (1988). Reasons for discontinuing hashish use in a group of Central European athletes: Journal of Drug Education Vol 18(1) 1988, 49-53.

- Fernberger, S. W. (1939). Review of Marihuana: America's new drug problem: Psychological Bulletin Vol 36(4) Apr 1939, 300-301.

- Fletcher, J. M., & Satz, P. (1977). A methodological commentary on the Egyptian study of chronic hashish use: Bulletin on Narcotics Vol 29(2) Apr-Jun 1977, 29-34.

- Foulon, L. (1979). Hashish and heroine: Considerations on interviews with drug addicts: Acta Psychiatrica Belgica Vol 79(3) May-Jun 1979, 343-354.

- Frantisek David, K., L, C., & H, D. (2004). Psychosocial context of marijuana use in school children: Ceska a Slovenska Psychiatrie Vol 100(6) 2004, 348-355.

- Frischknecht, H.-R., Sieber, B., & Waser, P. G. (1980). Behavioral effects of hashish in mice: II. Nursing behavior and development of the sucklings: Psychopharmacology Vol 70(2) Oct 1980, 155-161.

- Frischknecht, H.-R., Siegfried, B., Schiller, M., & Waser, P. G. (1985). Hashish extract impairs retention of defeat-induced submissive behavior in mice: Psychopharmacology Vol 86(3) Jun 1985, 270-273.

- Gibson, P. G. (1979). Chronic hashish use and personality profiles as measured by the California Psychological Inventory and the college student questionnaire in a population of adolescent Americans resident in the Near East: Dissertation Abstracts International.

- Girdano, D. A., & Girdano, D. D. (1974). Drug usage trends among college students: College Student Journal Vol 8(3) Sep-Oct 1974, 94-96.

- Graziani, G., & Gori-Savellini, S. (2003). Moreau de Tours: Hashish and psychiatry: Psichiatria e Psicoterapia Vol 22(3) Sep 2003, 234-243.

- Irvin, J. E., & Mellors, A. (1975). D9-tetrahydrocannabinol: Uptake by rat liver lysosomes: Biochemical Pharmacology Vol 24(2) Jan 1975, 305-307.

- Jamison, K., & McGlothlin, W. H. (1973). Drug usage, personality, attitudinal, and behavioral correlates of driving behavior: Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied Vol 83(1) Jan 1973, 123-130.

- Jarbe, T. U., & Henriksson, B. G. (1974). Discriminative response control produced with hashish, tetrahydrocannabinols (D8-THC and D9-THC), and other drugs: Psychopharmacologia Vol 40(1) 1974, 1-16.

- Jonckheere, P. (1973). Beyond hallucinogenic drugs: The case of Solange: Acta Psychiatrica Belgica Vol 73(4) Jul 1973, 497-509.

- Jones, H. (1975). Science, Common Sense, and Nonsense: PsycCRITIQUES Vol 20 (3), Mar, 1975.

- Korf, D. J. (1988). 20 years of use of illicit soft drugs in the Netherlands: A look back on prevalence studies: Tijdschrift voor Alcohol, Drugs en Andere Psychotrope Stoffen Vol 14(3) Jul 1988, 81-89.

- Langer, J. (1977). Drug entrepreneurs and dealing culture: Social Problems Vol 24(3) Feb 1977, 377-386.

- Leon-Carrion, J., & Vela-Bueno, A. (1991). Cannabis and cerebral hemispheres: A chrononeuropsychological study: International Journal of Neuroscience Vol 57(3-4) Apr 1991, 251-257.

- Macdonald, D., & Mansfield, D. (2001). Drugs and Afghanistan: Drugs: Education, Prevention & Policy Vol 8(1) Feb 2001, 1-6.

- Marcotte, D. B. (1972). Marijuana and mutism: American Journal of Psychiatry Vol 129(4) Oct 1972, 475-477.

- Matte, A. C. (1975). Effects of hashish on isolation induced aggression in wild mice: Psychopharmacologia Vol 45(1) 1975, 125-128.

- McDonough, J. H., Manning, F. J., & Elsmore, T. F. (1972). Reduction of predatory aggression rats following administration of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol: Life Sciences Vol 11(3, Pt 1) Feb 1972, 103-111.

- Milner, M. (2006). Hashish and literature: Alcoologie et Addictologie Vol 28(2) Jun 2006, 99-105.

- Mohammad, A. (1993). Mental symptoms among chronic (hashish) abusers: Arab Journal of Psychiatry Vol 4(2) Nov 1993, 105-112.

- Mora, G. (1989). Historical antecedents of modern psychopharmacology: Psychiatric Journal of the University of Ottawa Vol 14(1) Mar 1989, 279-281.

- Navarro, M., de Miguel, R., Rodriguez de Fonseca, F., Ramos, J. A., & Fernandez-Ruiz, J. J. (1996). Perinatal cannabinoid exposure modifies the sociosexual approach behavior and the mesolimbic dopaminergic activity of adult male rats: Behavioural Brain Research Vol 75(1-2) Feb 1996, 91-98.

- Oliva, K., Sieber, M., Stahli, R., & Angst, J. (1986). Consumption of hashish, tobacco and alcohol, and attitudes toward youth demonstrations as correlates of status inconsistency: Kolner Zeitschrift fur Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie Vol 38(1) Mar 1986, 110-122.

- Papadakis, D. P., Michael, C. M., Kephalas, T. A., & Miras, C. J. (1974). Effects of cannabis smoking in blood lactic acid and glucose in humans: Experientia Vol 30(10) 1974, 1183-1184.

- Pietzeker, A. (1975). Psychotic episodes after smoking hashish: Nervenarzt Vol 46(7) Jul 1975, 378-383.

- Ravenna, M., Cavazza, N., Nardelli, R., & Potente, R. (2001). Adolescent representations of ecstasy, cocaine, and hashish: Bollettino di Psicologia Applicata No 235 Sep-Dec 2001, 33-46.

- Rodrigo, M. D. B., Atance, J. A. R., Garcia, M. L. L., De Antonio Perez, V., & Llera, J. L. G. (2004). Withdrawal symptoms and other effects in young hashish smokers: Adicciones Vol 16(1) 2004, 19-30.

- Sarro, R. (1981). Psychedelics or psycholytics? The present problematic illuminated from the past: Revista de Psiquiatria y Psicologia Medica Vol 15(1) Jan-Mar 1981, 1-30.

- Schenk, J. (1974). The neurotic personality of hashish users: Zeitschrift fur Klinische Psychologie und Psychotherapie Vol 22(4) 1974, 340-351.

- Scherer, S. E. (1973). Hard and soft hallucinogenic drug users: Their drug taking patterns and objectives: International Journal of the Addictions Vol 8(5) 1973, 755-766.

- Sieber, B. (1982). Influence of hashish extract on the social behaviour of encountering male baboons (Papio c. anubis): Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior Vol 17(2) Aug 1982, 209-216.

- Sieber, B., Frischknecht, H.-R., & Waser, P. G. (1980). Behavioral effects of hashish in mice: I. Social interactions and nest-building behavior of males: Psychopharmacology Vol 70(2) Oct 1980, 149-154.

- Sieber, B., Frischknecht, H.-R., & Waser, P. G. (1980). Behavioral effects of hashish in mice: III. Social interactions between two residents and an intruder male: Psychopharmacology Vol 70(3) Oct 1980, 273-278.

- Sieber, B., Frischknecht, H.-R., & Waser, P. G. (1981). Behavioral effects of hashish in mice: IV. Social dominance, food dominance, and sexual behavior within a group of males: Psychopharmacology Vol 73(2) Apr 1981, 142-146.

- Siegel, R. K. (1974). Hashish Hallucinations: Discovery Rediscovered: PsycCRITIQUES Vol 19 (10), Oct, 1974.

- Siegel, R. K., & Hirschman, A. E. (1984). Hashish near-death experiences: Anabiosis: The Journal of Near-Death Studies Vol 4(1) Spr 1984, 69-86.

- Siegel, R. K., & Hirschman, A. E. (1985). Hashish and laughter: Historical notes and translations of early French investigations: Journal of Psychoactive Drugs Vol 17(2) Apr-Jun 1985, 87-91.

- Silva, A. S., & De Deus, A. A. (2005). Behaviors of consumers of hashish and mental health of adolescents: Comparative study: Analise Psicologica Vol 23(2) Apr-Jun 2005, 151-172.

- Simmen, R., von Arx, S., Staub, S., & Dittrich, A. (1981). International study on altered states of consciousness (ISASC): II. Results from the German-speaking part of Switzerland: Schweizerische Zeitschrift fur Psychologie und ihre Anwendungen/ Revue suisse de Psychologie pure et appliquee Vol 40(3) 1981, 201-218.

- Sorfleet, P. (1976). Dealing hashish: Sociological notes on trafficking and use: Canadian Journal of Criminology & Corrections Vol 18(2) Apr 1976, 123-151.

- Soueif, M. I. (1977). The Egyptian study of chronic cannabis use: A reply to Fletcher and Satz: Bulletin on Narcotics Vol 29(2) Apr-Jun 1977, 35-43.

- Stefanis, C., & et al. (1976). Chronic hashish use and mental disorder: American Journal of Psychiatry Vol 133(2) Feb 1976, 225-227.

- Tamir, A., Wolff, H., & Epstein, L. (1982). Health-related behavior in Israel adolescents: Journal of Adolescent Health Care Vol 2(4) Jun 1982, 261-265.

- Tennant, F. S. (1976). Dependency traits among parents of drug abusers: Journal of Drug Education Vol 6(1) 1976, 83-88.

- van Bilsen, H. (2007). Too Much of Nothing Can Make a Man Ill at Ease: PsycCRITIQUES Vol 52 (33), 2007.

- Vardaris, R. M. (1979). Grass in Greece: PsycCRITIQUES Vol 24 (6), Jun, 1979.

- Volavka, J., & et al. (1973). EEG, heart rate and mood change ("high") after cannabis: Psychopharmacology Vol 32(1) 1973, 11-25.

- Wolf, Y., Olenick-Shemesh, D., Addad, M., Green, D., & et al. (1995). Personal and situational factors in drug use as perceived by kibbutz youth: Adolescence Vol 30(120) Win 1995, 909-930.

- Yvorel, M. J.-J. (2006). A history of cannabis: Alcoologie et Addictologie Vol 28(2) Jun 2006, 107-112.

- Zangen, A., Solinas, M., Ikemoto, S., Goldberg, S. R., & Wise, R. A. (2006). Two Brain Sites for Cannabinoid Reward: Journal of Neuroscience Vol 26(18) May 2006, 4901-4907.

Cannabis resources | |

|---|---|

| General |

Portal · Cultivation (Outdoor · Indoor · Alternative methods) · Cannabis culture (420 · Film) · Drug · Health · Industrial · Legal · Medicinal · Spiritual |

| Preparations |

Bhang · Hashish · Kief · Shake · Shwag · Honey oil |

| Use |

Smoking · Blunt · Bong · Bowl · Chillum · Dugout · Gravity bong · Hookah · Joint · Pipe · Shotgun · Spots · Steamroller · Vaporizer |

| Strains |

AK47 · Acapulco gold · Afghan Kush · BC Bud · Black Jack · Chocolate Thai · Columbian Red · G-13 · Green Crack · Haze · Jock Horror · Kali Mist · Kushage · Lowryder · Matanuska tundra · Neville's haze · Northern Lights · OG Kush · Panama Red · Purple Haze · Santa Maria · Silver Haze · Skunk · Sour Diesel · Toronto Hydro · White Widow |

| Oral Consumption |

Cannabis foods · Tea · Green Dragon |

| Organizations |

AAMC · Assembly · BLCC · Buyers Club · CCRMG · DPA · FCA · GMM · LCA · LEAP · MPP · NORML · Political parties · POT · Promena · Rescheduling Coalition · ASA · SAFER · Spliff Committee · SSDP · THC Ministry · Therapeutics Alliance |

External links

Look up this page on

Wiktionary:

Hashish

- A recent publication on hashish production and trafficking in the Rif area of Morocco

- How to make bubble hash

- How to judge hashish quality

- Analysis of adulterated hashish

- A Collection of Hashish Photography

Further reading

- Hashish by Robert Connell Clarke, ISBN 0-929349-05-9

- Artificial Paradises by Charles Baudelaire; first edition 1860

- The Hasheesh Eater by Fitz Hugh Ludlow; first edition 1857

- Indoor Marijuana Horticulture, by Jorge Cervantes, ISBN 1-878823-29-9 ; 2001, reprinted 2005

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia (view authors). |