Assessment |

Biopsychology |

Comparative |

Cognitive |

Developmental |

Language |

Individual differences |

Personality |

Philosophy |

Social |

Methods |

Statistics |

Clinical |

Educational |

Industrial |

Professional items |

World psychology |

Psychology of music: Cognition · Ability · Training · Emotion

| Music education |

|---|

| Major instructional methodologies |

| Kodály Method - Orff Schulwerk - Dalcroze method - Suzuki method |

| Instructional settings |

| General music instruction - Extracurricular - Ensemble Chorus - Concert band - Marching band - Orchestra |

| International organizations |

| International Society for Music Education International Association for Jazz Education Organization of Kodaly Educators |

| National organizations in the United States |

| National Association for Music Education - Music Teachers National Association - American Choral Directors Association - American String Teachers Association - American School Band Directors Association |

Music education is a field of study associated with the teaching and learning of music.

In elementary schools, children often learn to play instruments such as keyboards or recorders, sing in small choirs, and learn about the elements of musical sound and history of music. Although music education in many nations has traditionally emphasized Western classical music, in recent decades music educators tend to incorporate application and history of non-western music to give a well-rounded musical experience and teach multiculturalism and international understanding. In primary and secondary schools, students may often have the opportunity to perform in some type of musical ensemble, such as a choir, orchestra, or school band: concert band, marching band, or jazz band. In some secondary schools, additional music classes may also be available.

At the university level, students in most arts and humanities programs may receive academic credit for taking music courses, which typically take the form of an overview course on the history of music, or a music appreciation course that focuses on listening to music and learning about different musical styles. In addition, most North American and European universities have some type of music ensemble in which students from various fields of study may participate such as a choir, concert band, marching band, or orchestra. Music education departments in North American and European universities often support interdisciplinary research in such areas as music psychology, music education historiography, educational ethnomusicology, and philosophy of education.

The study of Western art music is increasingly common in music education outside of North America and Europe, including Asian nations such as South Korea, Japan, and China. At the same time, Western universities and colleges are widening their curriculum to include music of non-Western cultures, such as the music of Africa or Bali (e.g. Gamelan music).

Music education also takes place in individualized, life-long learning, and community contexts. Both amateur and professional musicians typically take music lessons, short private sessions with an individual teacher. Amateur musicians typically take lessons to learn musical rudiments and beginner- to intermediate-level musical techniques.

History of Music Education in the U.S.A.[]

17th century[]

Music education in North America can be traced to the colonies of the seventeenth century. In the Southern United States, there existed no organized music education system. However, rote learning played a major role in the transmission of music traditions. In the Northern colonies, music was already an important consideration in the lives of the Pilgrims. The Bay Psalm Book, especially later editions, provided methods for solmization along with performance instruction. Thus Northern colonists could succeed in teaching themselves rudimentary music skills, as related to psalm singing. There was also much music in small town committee bands.

18th century[]

After the preaching of Reverend Thomas Symmes, the first singing school was created in 1717 in Boston, Massachusetts for the purposes of improving singing and music reading in the church. These singing schools gradually spread throughout the colonies. Reverend John Tufts published An Introduction to the Singing of Psalm Tunes Using Non-Traditional Notation which is regarded as the first music textbook in the colonies. Between 1700 to 1820, more than 375 tune books would be published by such authors as Samuel Holyoke, Francis Hopkinson, William Billings, and Oliver Holden.[1]

19th century[]

In 1832, Lowell Mason and George Webb formed the Boston Academy of Music with the purposes of teaching singing and theory as well as methods of teaching music. Mason published his Manuel of Instruction in 1834 which were based upon the music education works of Pestalozzian System of Education founded by Swiss educator Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi. This handbook gradually became used by many singing school teachers. In 1837-1838, the Boston School Committee allowed Lowell Mason to teach music in the Hawes School as a demonstration. This is regarded as the first time music education was introduced to public schools in the United States. In 1838 the Boston School Committee approved the inclusion of music in the curriculum and Lowell Mason became the first recognized supervisor of elementary music. In later years Luther Whiting Mason became the Supervisor of Music in Boston and spread music education into all levels of public education (grammar, primary, and high school). During the middle of the 19th century, Boston became the model to which many other cities across the United States included and shaped their public school music education programs.[2] Music methodology for teachers as a course was first introduced in the Normal School. The concept of classroom teachers in a school that taught music under the direction of a music supervisor was the standard model for public school music education during this century.

Early 20th century[]

In the United States, teaching colleges with four year degree programs developed from the Normal Schools and included music. Oberlin Conservatory first offered the Bachelor of Music Education degree. Osbourne G. McConathy, and American music educator introduced details for studying music for credit in Chelsea High School. Notable events in the history of music education in the early 20th century also include:

- Founding of the Music Supervisor's National Conference (changed to Music Educators National Conference in 1934) in Keokuk, Iowa in 1907.

- Rise of the school band and orchestra movement leading to performance oriented school music programs.

- Growth in music methods publications.

- Frances E. Clark develops and promotes phonograph record libraries for school use.

- Carl Seashore and his Measures of Musical Talent music apptitude test starts testing people in music.

Mid & Late 20th century[]

| Date | Major Event | Historical Importance for Music Education |

|---|---|---|

| 1950 | The Child's Bill of Rights in Music | A student-centered philosophy was formally espoused by MENC. |

| 1953 | The American School Band Directors Association formed | The band movement becomes organized. |

| 1957 | Launch of Sputnik | Increased curricular focus on science, math, technology with less emphasis on music education. |

| 1959 | Contemporary Music Project | The purpose of the project was to make contemporary music relevant in children by placing quality composers and performers in the learning environment. Leads to the Comprehensive Musicianship movement. |

| 1961 | American Choral Directors Association formed | The choral movement becomes organized. |

| 1965 | National Endowment for the Arts | Federal financial support and recognition of the value music has in society. |

| 1967 | Yale Seminar | Federally supported development of arts education focusing on quality music classroom literature. Julliard Project leads to the compilation and publication of musical works from major historical eras for elementary and secondary schools. |

| 1967 | Tanglewood Symposium | Establishment of a unified and ecletic philosophy of music education. Specific emphasis on youth music, special education music, urban music, and electronic music. |

| 1969 | GO Project | 35 Objectives listed by MENC for quality music education programs in public schools. Published and recommended for music educators to follow. |

| 1978 | The Ann Arbor Symposium | Emphasized the impact of learning theory in music education in the areas of: auditory perception, motor learning, child development, cognitive skills, memory processing, affect, and motivation. |

| 1984 | Becoming Human Through Music symposium | "The Wesleyan Symposium on the Perspectives of Social Anthropology in the Teaching and Learning of Music" (Middletown, Connecticut, August 6-10, 1984). Emphasized the importance of cultural context in music education and the cultural implications of rapidly changing demographics in the United States. |

| 1994 | National Standards for Music Education | For much of the 1980s, there was a call for educational reform and accountability in all curricular subjects. This led to the National Standards for Music Education introduced by MENC. The MENC standards were adopted by some states, while other states have produced their own standards or largely eschewed the standards movement. |

| 1999 | The Housewright Symposium / Vision 2020 | Examined changing philosophies and practices and predicted how American music education will (or should) look in the year 2020. |

| 2007 | Tanglewood II: Charting the Future | Reflected on the 40 years of change in music education since the first Tanglewood Symposium of 1967, developing a declaration regarding priorities for the next forty years. |

Standards and assessment[]

Standards are curricular statements used to guide educators in determining objectives for their teaching. Use of standards became a common practice in many nations during the 20th century. For much of its existence, the curriculum for music education in the United States was determined locally or by individual teachers. In recent decades there has been a significant move toward adoption of regional and/or national standards. MENC: The National Association for Music Education, created nine voluntary content standards, called the National Standards for Music Education.[1]These standards call for:

- Singing, alone and with others, a varied repertoire of music.

- Performing on instruments, alone and with others, a varied repertoire of music.

- Improvising melodies, variations, and accompaniments.

- Composing and arranging music within specified guidelines.

- Reading and notating music.

- Listening to, analyzing, and describing music.

- Evaluating music and music performances.

- Understanding relationships between music, the other arts, and disciplines outside the arts.

- Understanding music in relation to history and culture.

Many states and school districts have adopted their own standards for music education. Often, these local standards are related in some way to the National Standards.

Washington State has piloted a classroom based performance assessment which requires 5th and higher grade students to compose music on a staff and sight sing from sheet music without the aid of instruments. It is designed to assess standards expected to be attained by all students. [3] Sight singing is a learning requirement in the state at the 8th grade level. Other states are evaluating possible performance assessments as well.

Instructional methodologies[]

While instructional strategies are bound by the music teacher and the music curriculum in his or her area, many teachers rely heavily on one of many instructional methodologies that emerged in recent generations and developed rapidly during the latter half of the 20th Century:

Major international music education methods[]

Kodály method[]

- Main article: Kodály Method

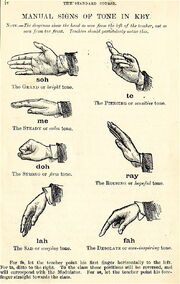

Depiction of Curwen's Solfege hand signs. This version includes the tonal tendencies and interesting titles for each tone.

Zoltán Kodály (1882-1967) was a prominent Hungarian music educator and composer who stressed the benefits of physical instruction and response to music. Although not really an educational method, his teachings reside within a fun, educational framework built on a solid grasp of basic music theory and music notation in various verbal and written forms. Kodály's primary goal was to instill a lifelong love of music in his students and felt that it was the duty of the child's school to provide this vital element of education. Some of Kodály's trademark teaching methods include the use of solfege hand signs, musical shorthand notation (stick notation), and rhythm solmnization (verbalization).

Orff Schulwerk[]

- Main article: Orff Schulwerk

Carl Orff was a prominent German composer. The Orff Schulwerk is considered an "approach" to music education. It begins with a student's innate abilities to engage in rudimentary forms of music, using basic rhythms and melodies. Orff considers the whole body a percussive instrument and students are lead to develop their music abilities in a way that parallels the development of western music. The approach encourages improvisation and discourages adult pressures and mechanical drill, fostering student self-discovery. Carl Orff developed a special group of instruments, including modifications of the glockenspiel, xylophone, metallophone, drum, and other percussion instruments to accommodate the requirements of the Schulwerk courses.[4]

Suzuki method[]

- Main article: Suzuki method

The Suzuki method was developed by Shinichi Suzuki in Japan shortly after World War II, and it uses music education to enrich the lives and moral character of its students. The movement rests on the double premise that "all children can be well educated" in music, and that learning to play music at a high level also involves learning certain character traits or virtues which make a person's soul more beautiful. The primary method for achieving this is centered around creating the same environment for learning music that a person has for learning their native language. This 'ideal' environment includes love, high-quality examples, praise, and a time-table set by the student's developmental readiness for learning a particular technique. While the Suzuki Method is quite popular internationally, within Japan its influence is less significant than the Yamaha Method, founded by Genichi Kawakami in association with the Yamaha Music Foundation.[5]

Dalcroze method[]

- Main article: eurhythmics

The Dalcroze method was developed in the early 1900s by Swiss musician and educator Émile Jaques-Dalcroze. The method is divided into three fundamental concepts - the use of solfege, improvisation, and eurhythmics. Sometimes referred to as "rhythmic gymnastics", eurhythmics teaches concepts of rhythm, structure, and musical expression using movement, and is the concept for which Dalcroze is best known. It focuses on allowing the student to gain physical awareness and experience of music through training that takes place through all of the senses, particularly kinesthetic. According to the Dalcroze method, music is the fundamental language of the human brain and therefore deeply connected to what human beings are.

Other Notable methods[]

In addition to the four major international methods described above, other approaches have been influential. Lesser-known methods are described below:

Gordon Music Learning Theory[]

This method is based on an extensive body of research and field testing by Edwin E. Gordon and others. Music Learning Theory provides the music teacher a comprehensive method for teaching musicianship through audiation, Gordon's term for hearing music in the mind with understanding. Teaching methods help music teachers establish sequential curricular objectives in accord with their own teaching styles and beliefs.[6]

Conversational Solfege[]

Deriving influence from both Kodály methodology and Gordon's Music Learning Theory, Conversational Solfege was developed by Dr. John M. Feierabend, chair of music education at the Hartt School at the University of Hartford. The philosophy of this method is to view music as an aural art with a literature based curriculum. The sequence of this methodology involves a 12 step process to teach music literacy. Steps include rhythm and tonal patterns and decoding the patterns using syllables and notation.

Carabo-Cone Method[]

This early-childhood approach sometimes referred to as the Sensory-Motor Approach to Music was developed by the violinist Madeleine Carabo-Cone. This approach involves using props, costumes, and toys for children to learn basic musical concepts of staff, note duration, and the piano keyboard. The concrete environment of the specially planned classroom allows the child to learn the fundamentals of music by exploring through touch.[7]

MMCP[]

- Main article: MMCP

The Manhattanville Music Curriculum Project was developed in 1965 and is an alternative method in shaping positive attitudes toward music education. This creative approach centers around the student being the musican and involved in the discovery process. The teacher gives the student freedom to create, perform, improvise, conduct, research, and investigate different facets of music in a spiral curriculum.

Applied Groovology and Path Bands[]

Applied Groovology and Path Bands are new methods for community music education in urban settings devised by American ethnomusicologist http://www.musicgrooves.org/bios.php Dr. Charles Keil]. A renowned expert who has published several influential scholarly books on music from many parts of the world (Chicago blues, polka, Greek Macedonian, Nigerian Tiv, Afro-Latin music styles, etc), Dr Keil asserts that the natural power of music is underappreciated and underutilized in modern industrial societies that feature passive consumption through mass media rather than active participation in music. Keil advocates that parents should encourage their children to more freely experience the natural joys of improvised music and dance through “grooving and dandling”. Keil has also developed the "Path Band" approach to the use of improvised multicultural brass bands for active lifelong participation in music. Keil's methods are of growing interest among North American music educators and therapists, and are also attracting attention in Japan. [8]

Integration with other subjects[]

Some schools and organizations promote integration of arts classes, such as music, with other subjects, such as math, science, or English. It is thought that by integrating the different curricula will help each subject to build off of one another, enhancing the overall quality of education.

One example is the Kennedy Center's "Changing Education Through the Arts" program. CETA defines arts integration as finding a natural connection(s) between one or more art forms (dance, drama/theater, music, visual arts, storytelling, puppetry, and/or creative writing) and one or more other curricular areas (science, social studies, English language arts, mathematics, and others) in order to teach and assess objectives in both the art form and the other subject area. This allows a simultaneous focus on creating, performing, and/or responding to the arts while still addressing content in other subject areas.[2]

Music advocacy[]

In some communities - and even entire national education systems - music is provided very little support as an academic subject area, and music teachers feel that they must actively seek greater public endorsement for music education as a legitimate subject of study. This perceived need to change public opinion has resulted in the development of a variety of approaches commonly called "music advocacy". Music advocacy comes in many forms, some of which are based upon legitimate scholarly arguments and scientific findings, while other examples rely on unconvincing data and remain rather controversial.

Among the more recent high-profile music advocacy projects that have become the subject of widespread controversy are the "Mozart Effect" (which is now widely believed to be based on misinterpretation and exaggeration, or even pseudoscience), and the National Anthem Project, which sought to harness American patriotic fervor during early stages of the "War on Terrorism" (2004-2007) with the hope that music education could be "saved" through the resulting increase in publicity for school music programs.

Many contemporary music scholars assert that music advocacy will only be truly effective when based on empirically sound arguments that transcend political motivations and personal agendas. This position regarding music advocacy has especially been advanced by music education philosophers (such as Bennett Reimer, Estelle Jorgensen, David J. Elliott, Wayne Bowman, etc.), yet a gap remains between the discourse of music education philosophy and the actual practices of music teachers and music organization executives.

See also[]

- Braille music

- Musical ability

- Musical instrumnet

- Music perception

- Music therapy

Influential music educators[]

- Leonard Bernstein

- Hildegard of Bingen

- Nadia Boulanger

- Allen Britton

- E. Azalia Hackley

- Frederick Fennell

- Edwin Gordon

- Arnold Jacobs

- Emile Jaques-Dalcroze

- Genichi Kawakami

- Zoltán Kodály

- Joseph E. Maddy

- Lowell Mason

- Luther Whiting Mason

- Carl Orff

- Bernarr Rainbow

- R. Murray Schafer

- Shinichi Suzuki

- Peter Tileston

International professional organizations[]

- International Society for Music Education[9]

- International Association for Jazz Education[10]

- OAKE: Organization of Kodaly Educators[11]

- AOSA: American Orff Schulwerk Association[12]

National professional organizations[]

- MENC: The National Association for Music Education [3]

- MTNA: Music Teachers National Association [4]

- American Choral Directors Association [5]

- American String Teachers Association [6]

Notes[]

- ↑ http://www.bsu.edu/classes/bauer/hpmused/colonial.html

- ↑ http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-4294(199022)38%3A2%3C79%3APOANSM%3E2.0.CO%3B2-F#abstract

- ↑ "Zoo Tunes"

- ↑ http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=U1ARTU0002658

- ↑ This is verified in numerous publications. See Genichi Kawakami, Reflections on Music Popularization (Yamaha, 1987), Shinobu Oku, Music Education in Japan (Nara: Neiraku Arts Centre, 1994), and David G. Hebert, Music Competition, Cooperation, and Community: An Ethnography of a Japanese School Band (Ann Arbor: Proquest/UMI, 2005).

- ↑ http://www.giml.org/home.php

- ↑ http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/custom/portlets/recordDetails/detailmini.jsp?_nfpb=true&_&ERICExtSearch_SearchValue_0=ED034358&ERICExtSearch_SearchType_0=eric_accno&accno=ED034358

- ↑ Keil's work has been cited in numerous music education journals, including Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education; Philosophy of Music Education Review; Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education. His books were cited in the journal Ethnomusicology as among the most significant in the latter half of the 20th century, and his work is acknowledged as a basis for the popular Nordoff-Robbins method of music therapy. He is also among the most frequently cited ethnomusicologists in related fields such as sociology of music and music psychology. Keil is keynote speaker of the 2008 Cultural Diversity in Music Education international conference, and was a keynote speaker at the recent Japan International Musicological Society conference and the 2000 symposium Around the Sound: Popular Music in Performance, Education, and Scholarship.

- ↑ International Society for Music Education

- ↑ IAJE: International Association for Jazz Education

- ↑ OAKE: Organization of Kodaly Educators

- ↑ AOSA: American Orff Schulwerk Association

Bibliography[]

- DeBakey, Michael E., MD. Leading Heart Surgeon, Baylor College of Music.

- Kertz-Welzel, Alexandra. "The Singing Muse: Three Centuries of Music Education in Germany." Journal of Historical Research in Music Education XXVI no. 1 (2004): 8-27.

- Kertz-Welzel, Alexandra. "Didaktik of Music: A German Concept and its Comparison to American Music Pedagogy." International Journal of Music Education (Practice) 22 No. 3 (2004): 277-286.

- Kertz-Welzel, Alexandra. "General Music Education in Germany Today: A Look at How Popular Music is Engaging Students." General Music Today 18 no. 2 (Winter 2005): 14-16.

- Kertz-Welzel, Alexandra. "Performing with Understanding: Die National Standards for Music Education und ihre internationale Bedeutung." Diskussion Musikpädagogik 27 (2005): 34-39.

- Kertz-Welzel, Alexandra. Every Child for Music: Musikpädagogik und Musikunterricht in den USA. Musikwissenschaft/Musikpädagogik in der Blauen Eule, no. 74. Essen, Germany: Verlag Die Blaue Eule, 2006. ISBN 3-89924-169-X.

- National Standards for Arts Education. Reston, VA: Music Educators National Conference (MENC), 1994. ISBN 1-56545-036-1.

- Neurological Research, Vol. 19, February 1997.

- Ratey, John J., MD. A User’s Guide to the Brain. New York: Pantheon Books, 2001.

- Rauscher, F.H., et al. “Music and Spatial Task Performance: A Causal Relationship,” University of California, Irvine, 1994.

- Weinberger, Norm. “The Impact of Arts on Learning.” MuSICa Research Notes 7, no. 2 (Spring 200).

- Pete Moser and George McKay, eds. (2005) Community Music: A Handbook. Russell House Publishing. ISBN 1-903855-70-5.

External links[]

- International Society for Music Education

- MayDay Group

- Dr Fung's International Music Education Links

- Comprehensive Music Education website of About.Com

- Links from MENC: The National Association for Music Education

- American Orff-Schulwerk Association

- Website resource of UK national music education magazine, Zone

- Gordon Institute for Music Learning

- Percussive Arts Society - Percussion resource for education, research, performance and appreciation .

- Research and Issues in Music Education

- International Journal of Education and the Arts

- Italian Suzuki Institute

- Bridge to Music, Music School Directory Bridge to Music is an on line guide to music schools, organized by degree, program and location.

- The Blue Shoe Project - Blues Music Education

- Music Education World

- You Are a Drummer - free percussion education resource

| By country: |

Australia · Brazil · Canada · China · France · Germany · India · Israel · Japan · Korea · Russia · United Kingdom · United States · More... |

| By subject: |

Agricultural · Art · Bilingual · Chemistry · Language · Legal · Mathematics · Military · Music · Peace · Performing arts · Physics · Reading · Religious · Science · Sex · Technology · Vocational · More... |

| Stages: |

Preschool · Kindergarten · Primary Elementary education· Secondary Middle school education · Post-secondary (Vocational, Higher education (Tertiary, Quaternary)) · More... |

| Alternatives: |

Autodidacticism · Education reform · Gifted education · Homeschooling · Nontraditional education · Polymath · Religious education · Remedial education · Special education · More... |

| Professional education |

Clinical methods training · Counselor education · Medical · Nursing education · Paraprofessional education · Social work education · Teacher education · |

| General: |

List · Glossary · Philosophy · Psychology · Technology · Stubs |

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia (view authors). |