Assessment |

Biopsychology |

Comparative |

Cognitive |

Developmental |

Language |

Individual differences |

Personality |

Philosophy |

Social |

Methods |

Statistics |

Clinical |

Educational |

Industrial |

Professional items |

World psychology |

Social psychology: Altruism · Attribution · Attitudes · Conformity · Discrimination · Groups · Interpersonal relations · Obedience · Prejudice · Norms · Perception · Index · Outline

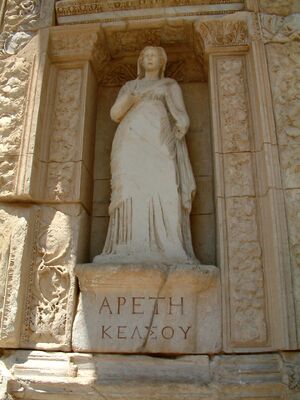

Personification of virtue Greek ἀρετή) in Celsus Library in Ephesos, Turkey

Virtue (Latin virtus; Greek ἀρετή) is moral excellence of a person. A virtue is a character trait valued as being good. The conceptual opposite of virtue is vice.

The Greek word ἀρετή (Arete (excellence}) has not come into ordinary English. The English word virtue is derived from the Latin word virtus which is in turn from vir meaning "man" in the masculine sense. The word virtus means "the male function" conceived in terms of strength or force; hence "the power to accomplish". [The unrelated Latin word vis means simply "power" or "violence"; ancient grammarians were unable to distinguish the two words.] Cf. Ernout-Meillet, Dictionnaire étymologique de la langue latine: Histoire des mots. (The Roman virtue called virtus, indeed, specifically meant courage or strength of arms, rather than 'virtue' in the broader English sense.)

Due to ancient social norms and these linguistic subtleties, virtus was sometimes identified with the masculine warlike virtues such as courage. This has sometimes led to a sense of irony concerning the supposed etymology. In English the word virtue is often used to refer to a woman's chastity. As the philosopher Leo Strauss expresses it, "The mystery of Western thought is how a term that originally meant the manliness of a man came to mean the chastity of a woman."

Virtue can also be meant in another way. Virtue can either have normative or moral value; i.e. the virtue of a knife is to cut, the virtue of an excellent knife is to cut well (this is its normative value) vs. the virtues of reason, prudence, chastity, etc. (which have moral value).

In the Greek it is more properly called ἠθικὴ ἀρετή (ēthikē aretē). It is "habitual excellence". It is something practiced at all times. The virtue of perseverance is needed for all and any virtue since it is a habit of character and must be used continuously in order for any person to maintain oneself in virtue.

The four virtues[]

The four classic Western cardinal virtues are:

- temperance : σωφροσύνη (sōphrosynē)

- prudence : φρόνησις (phronēsis)

- fortitude : ἀνδρεία (andreia)

- justice : δικαιοσύνη (dikaiosynē)

This enumeration is traced to Greek philosophy, being listed by both Plato and Socrates.

The unity of the virtues[]

The name "cardinal" is derived from the term cardo meaning hinge, which depicts the view that these four virtues are pivotal to any life of virtue.

Classically, some philosophers, most notably Plato and Aristotle, said that in order to pursue any of these virtues perfectly, one would have to master them all. For example, in order to be just, one must be wise. The thesis of the unity of the virtues is controversial - one might argue that humans can be courageous without being wise - but it is often defended, particularly in Plato's early dialogues, by the claim that all virtues are a single sort of knowledge, perhaps 'knowledge of good and evil'. Thus, to fail to possess one of the virtues shows that one lacks the knowledge required for the possession of any of the virtues.

Aristotle says the virtues are harmonized:

- dianoethic (built by rationality;

- νοῦς τῶν ἀρχῶν (nous tōn archōn) - understanding of substance,

- ἐπιστήμη (epistēmē) - science,

- σοφία (sophia) - wisdom,

- τέχνη (technē) - practical craft,

- φρόνησις (phronēsis) - practical mind)

- and ethic (built by custom;

- main:

- ἀνδρεία (andreia) - courage,

- σωφρoσύνη (sōphrosynē) - temperance;

- property-based:

- ἐλευθεριότης (eleutheriotēs) - generosity,

- μεγαλoπρεπεία (megaloprepeia) - goodwilling;

- honor-based:

- μεγαλoψυχία (megalopsychia) - pride,

- φιλoτιμία (philotimia) - assertivity,

- πραότης (praotēs) - control of anger;

- social:

- εὐτραπελία (eutrapelia) - wittiness,

- ἀλήθεια (alētheia) - truthfulness,

- φιλία (philia) - friendliness;

- political:

- δικαιoσύνη (dikaiosynē) - justice)

- main:

virtues.

Nietzsche is one of the more notable philosophers who explicitly denies the unity of the virtues, asserting that they are mutually incompatible. Interestingly, Nietzsche also asserts that having one virtue is better than having many, for 'it is more of a knot for fate to hold on to.'

Prudence and virtue[]

Seneca, the Roman Stoic said that perfect prudence is indistinguishable from perfect virtue. His point was that if you take the longest view, and consider all the consequences, in the end, a perfectly prudent person would act in the same way as a perfectly virtuous person. Many people have found it valuable to determine how each of the virtues is prudent, as well as how they harmonize.

The Christian virtues[]

- See also: Seven virtues

In Christianity, the theological virtues are faith, hope and charity or love/agape, a list which comes from 1 Corinthians 13:13 (νυνι δε μενει πιστις ελπις αγαπη τα τρια ταυτα μειζων δε τουτων η αγαπη pistis, elpis, agape). These are said to perfect one's love of God and Man and therefore (since God is super-rational) to harmonize and partake of prudence.

The Roman virtues[]

- virtus - manliness, courage

- dignitas

- pietas - piety, deference to the divine

- gravitas

- auctoritas

- religio

The Buddhist virtues[]

- Main article: Noble Eightfold Path

- Right Viewpoint - Realizing the Four Noble Truths (samyag-dṛṣṭi, sammā-diṭṭhi)

- Right Values - Commitment to mental and ethical growth in moderation (samyak-saṃkalpa, sammā-saṅkappa)

- Right Speech - One speaks in a non hurtful, not exaggerated, truthful way (samyag-vāc, sammā-vācā)

- Right Actions - Wholesome action, avoiding action that would do harm (samyak-karmānta, sammā-kammanta)

- Right Livelihood - One's job does not harm in any way oneself or others; directly or indirectly (weapon maker, drug dealer, etc.) (samyag-ājīva, sammā-ājīva}

- Right Effort - One makes an effort to improve (samyag-vyāyāma, sammā-vāyāma)

- Right Mindfulness - Mental ability to see things for what they are with clear consciousness (samyak-smṛti, sammā-sati)

- Right Meditation - State where one reaches enlightenment and the ego has disappeared (samyak-samādhi, sammā-samādhi)

- Main article: Sila

- To refrain from taking life.

- To refrain from taking that which is not freely given (stealing).

- To refrain from sensual misconduct (improper sexual behavior).

- To refrain from lying.

- To refrain from intoxicants which lead to loss of mindfulness.

- To refrain from eating at the wrong time (only eat from sunrise to noon).

- To refrain from dancing, using jewellery, going to shows, etc.

- To refrain from using a high, luxurious bed.

- Main article: Pāramitā

- Dāna pāramī : generosity, giving of oneself

- Sīla pāramī : virtue, morality, proper conduct

- Nekkhamma pāramī : renunciation

- Paññā pāramī : transcendental wisdom, insight

- Viriya (also spelled vīriya) pāramī : energy, diligence, vigour, effort

- Khanti pāramī : patience, tolerance, forbearance, acceptance, endurance

- Sacca pāramī : truthfulness, honesty

- Adhiṭṭhāna (adhitthana) pāramī : determination, resolution

- Mettā pāramī : loving-kindness

- Upekkhā (also spelled upekhā) pāramī : equanimity, serenity

Samurai values[]

In Hagakure, the quintessential book of the samurai, Yamamoto Tsunetomo encapsulates his views on 'virtue' in the four vows he makes daily:

- Never to be outdone in the Way of the Samurai.

- To be of good use to the master.

- To be filial to my parents.

- To manifest great compassion, and act for the sake of Man.

Tsunetomo goes on to say:

If one dedicates these four vows to the gods and Buddhas every morning, he will have the strength of two men and never slip backward. One must edge forward like the inchworm, bit by bit. The gods and Buddhas, too, first started with a vow.

Virtues and values[]

Virtues can be placed into a broader context of values. Each individual has a core of underlying values that contribute to our system of beliefs, ideas and/or opinions (see value in semiotics). Integrity in the application of a value ensures its continuity and this continuity separates a value from beliefs, opinion and ideas. In this context a value (e.g. Truth or Equality or Greed) is the core from which we operate or react. Societies have values that are shared among many of the participants in that culture. An individuals' values typically are largely but not entirely in agreement with their culture's values.

Individual virtues can be grouped into one of four categories of values:

- Ethics (virtue - vice, good - bad, moral - immoral - amoral, right - wrong, permissible - impermissible)

- Aesthetics (beautiful, ugly, unbalanced, pleasing)

- Doctrinal (political, ideological, religious or social beliefs and values)

- Innate/Inborn (inborn values such as reproduction and survival, a controversial category)

A value system is the ordered and prioritized set of values (usually of the ethical and doctrinal categories described above) that an individual or society holds.

Some virtues (a virtue is a character trait valued as being good) recognized in various Western cultures of the world include:

| width="20%" align="left" valign="top" |

- altruism

- appreciation

- assertiveness

- autonomy

- awareness

- balance

- being beautiful in spirit

- benevolence

- charity

- chastity

- cleanliness

- commitment

- compassion

- confidence

- consciousness

- continence

- cooperativeness

- courage

- courteousness

- creativity

- critical thinking

| width="20%" align="left" valign="top" |

- curiosity

- dependability

- detachment

- determination

- diligence

- discipline

- empathy

- endurance

- enthusiasm

- excellence

- fairness

- faith

- fidelity

- focus

- foresight

- forgiveness

- fortitude

- freedom

- free will

- friendliness

| width="20%" align="left" valign="top" |

- generosity

- happiness

- helpfulness

- honesty

- honour

- hopefulness

- hospitality

- humility

- humor

- idealism

- imagination

- impartiality

- independence

- innocence

- integrity

- intuition

- inventiveness

- justice

- kindness

- lovingness

- loyalty

- mercy

- moderation

| width="20%" align="left" valign="top" |

- manners

- modesty

- morality

- nurturing

- obedience

- openness

- optimism

- patience

- peacefulness

- perfection

- perseverance

- piety

- potential

- prudence

- purposefulness

- respectfulness

- responsibility

- restraint

- sacrifice

- self-awareness

| width="20%" align="left" valign="top" |

- self-discipline

- self-esteem

- self-reliance

- self-respect

- sensitivity

- sharing

- sincerity

- spirituality

- sympathy

- tactfulness

- temperance

- trustworthiness

- truth

- truthfulness

- understanding

- unselfishness

- wisdom

|}

Virtue and vice[]

The opposite of a virtue is a vice. One way of organizing the vices is as the corruption of the virtues. Thus the cardinal vices would be folly, venality, cowardice and lust. The Christian theological vices would be blasphemy, despair, and hatred.

However, as Aristotle noted, the virtues can have several opposites. Virtues can be considered the mean between two extremes. For instance, both cowardice and rashness are opposites of courage; contrary to prudence are both over-caution and insufficient caution. A more "modern" virtue, tolerance, can be considered the mean between the two extremes of narrow-mindedness on the one hand and soft-headedness on the other. Vices can therefore be identified as the opposites of virtues, but with the caveat that each virtue could have many different opposites, all distinct from each other.

Capital Vices and Virtues[]

The seven capital vices or seven deadly sins suggest a classification of vices and were enumerated by Thomas Aquinas in the 13th century. The Catechism of the Catholic Church mentions them as "capital sins which Christian experience has distinguished, following St. John Cassian and St. Gregory the Great."[1] "Capital" here means that these sins stand at the head (Latin caput) of the other sins which proceed from them, e.g., theft proceeding from avarice and adultery from lust.

These vices are pride, envy, avarice, anger, lust, gluttony, and sloth. The opposite of these vices are the following virtues: meekness, humility, generosity, tolerance, chastity, moderation, and zeal (meaning enthusiastic devotion to a good cause or an ideal). These virtues are not exactly equivalent to the Seven Cardinal or Theological Virtues mentioned above. Instead these capital vices and virtues can be considered the "building blocks" that rule human behaviour. Both are acquired and reinforced by practice and the exercise of one induces or facilitates the others.

Ranked in order of severity as per Dante's Divine Comedy (in the Purgatorio), the seven deadly vices are:

- Pride or Vanity — an excessive love of self (holding self out of proper position toward God or fellows; Dante's definition was "love of self perverted to hatred and contempt for one's neighbor"). In the Latin lists of the Seven Deadly Sins, pride is referred to as superbia.

- Avarice (covetousness, Greed) — a desire to possess more than one has need or use for (or, according to Dante, "excessive love of money and power"). In the Latin lists of the Seven Deadly Sins, avarice is referred to as avaritia.

- Lust — excessive sexual desire. Dante's criterion was "lust detracts from true love". In the Latin lists of the Seven Deadly Sins, lust is referred to as luxuria.

- Wrath or Anger — feelings of hatred, revenge or even denial, as well as punitive desires outside of justice (Dante's description was "love of justice perverted to revenge and spite"). In the Latin lists of the Seven Deadly Sins, wrath is referred to as ira.

- Gluttony — overindulgence in food, drink or intoxicants, or misplaced desire of food as a pleasure for its sensuality ("excessive love of pleasure" was Dante's rendering). In the Latin lists of the Seven Deadly Sins, gluttony is referred to as gula.

- Envy or jealousy; resentment of others for their possessions (Dante: "Love of one's own good perverted to a desire to deprive other men of theirs"). In the Latin lists of the Seven Deadly Sins, envy is referred to as invidia.

- Sloth or Laziness; idleness and wastefulness of time allotted. Laziness is condemned because others have to work harder and useful work can not get done. (also accidie, acedia)

Several of these vices interlink, and various attempts at causal hierarchy have been made. For example, pride (love of self out of proportion) is implied in gluttony (the over-consumption or waste of food), as well as sloth, envy, and most of the others. Each sin is a particular way of failing to love God with all one's resources and to love fellows as much as self. The Scholastic theologians developed schema of attribute and substance of will to explain these sins.

The 4th century Egyptian monk Evagrius Ponticus defined the sins as deadly "passions," and in Eastern Orthodoxy, still these impulses are characterized as being "Deadly Passions" rather than sins. Instead, the sins are considered to invite or entertain these passions. In the official Catechism of the Catholic Church published in 1992 by Pope John Paul II, these seven vices are considered moral transgression for Christians and the virtues should complement the Ten Commandments and the Beatitudes as the basis for any true Morality.

Virtue in Chinese philosophy[]

"Virtue", translated from Chinese de (德), is also an important concept in Chinese philosophy, particularly Daoism. De (Template:Zh-c; pinyin: dé

- Wade-Giles

- te

) originally meant normative "virtue" in the sense of "personal character; inner strength; integrity", but semantically changed to moral "virtue; kindness; morality". Note the semantic parallel for English virtue, with an archaic meaning of "inner potency; divine power" (as in "by virtue of") and a modern one of "moral excellence; goodness".

Confucian moral manifestations of "virtue" include ren ("humanity"), xiao ("filial piety"), and zhong ("loyalty") In Confucianism the notion of ren according to Simon Leys means "humanity" and "goodness". Originally ren had the archaic meaning in the Confucian Book of Poems of "virility", then progressively took on shades of ethical meaning. (On the origins and transformations of this concept see Lin Yu-sheng: "The evolution of the pre-Confucian meaning of jen and the Confucian concept of moral autonomy," Monumenta Serica, vol31, 1974-75.)

The Daoist concept of De, however, is more subtle, pertaining to the "virtue" or ability that an individual realizes by following the Dao ("the Way"). One important normative value in much of Chinese thinking is that one's social status should result from the amount of virtue that one demonstrates rather than from one's birth. In the Analects, Confucius explains de: "He who exercises government by means of his virtue may be compared to the north polar star, which keeps its place and all the stars turn towards it." (2/1, tr. James Legge)[1]

Virtue in modern psychology[]

Martin Seligman and other researchers involved in the positive psychology movement, frustrated by psychology's tendency to focus on dysfunction rather than on what makes a healthy and stable personality, set out to develop a list of "character strengths and virtues applicable to the widest possible range of human cultures. Although few if any virtues are truly universally valued, Seligman claims that the ones on his list are all considered important by an overwhelming majority of cultures; although rare communities that do not admire kindness or courage may exist, they are clearly exceptional.

The researchers discovered a total of twenty-four virtues that are universal or nearly so, divided into six basic types.

- Wisdom and Knowledge: creativity, curiosity, open-mindedness, love of learning, perspective

- Courage: bravery, persistence, integrity, vitality

- Humanity: love, kindness, social intelligence

- Justice: citizenship, fairness, leadership

- Temperance: forgiveness and mercy, humility and modesty, prudence, self-regulation

- Transcendence: appreciation of beauty and excellence, gratitude, hope, humor, spirituality

References[]

- New Catholic Encyclopedia, Catholic University of America, 1967. pg 704.

See also[]

- Aretology

- Bushido

- Chivalry

- Consequentialism

- Epistemic virtue

- Ethics

- Five Virtues (Sikh)

- Goodness

- Intellectual virtues

- Knightly Virtues

- Morality

- Paideia

- Prosocial behavior

- Seven Deadly Sins

- Sin

- Social justice

- Three Jewels of the Tao

- Three theological virtues.

- Value theory

- Vice

- Virtue ethics

- Virtues of Ultima

External links[]

- Cardinal, Contrary, Heavenly and other Virtues

- Virtues in Quran

- The Four Virtues

- Virtues Project International

- VirtueScience.com

- Virtue Magazine

- Catholic Encyclopedia "Cardinal Virtues"

- Summa Theologica "Second Part of the Second Part"

| General: Philosophy: Eastern - Western | History of philosophy: Ancient - Medieval - Modern | Portal |

| Lists: Basic topics | Topic list | Philosophers | Philosophies | Glossary of philosophical "isms" | Philosophical movements | Publications | Category listings ...more lists |

| Branches: Aesthetics | Ethics | Epistemology | Logic | Metaphysics | Philosophy of: Education, History, Language, Law, Mathematics, Mind, Philosophy, Politics, Psychology, Religion, Science, Social philosophy, Social Sciences |

| Schools: Agnosticism | Analytic philosophy | Atheism | Critical theory | Determinism | Dialectics | Empiricism | Existentialism | Humanism | Idealism | Logical positivism | Materialism | Nihilism | Postmodernism | Rationalism | Relativism | Skepticism | Theism |

| References: Philosophy primer | Internet Encyclo. of Philosophy | Philosophical dictionary | Stanford Encyclo. of Philosophy | Internet philosophy guide |

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia (view authors). |