Assessment |

Biopsychology |

Comparative |

Cognitive |

Developmental |

Language |

Individual differences |

Personality |

Philosophy |

Social |

Methods |

Statistics |

Clinical |

Educational |

Industrial |

Professional items |

World psychology |

Social psychology: Altruism · Attribution · Attitudes · Conformity · Discrimination · Groups · Interpersonal relations · Obedience · Prejudice · Norms · Perception · Index · Outline

Consensus decision-making is a group decision making process that not only seeks the agreement of most participants, but also the resolution or mitigation of minority objections. Consensus is usually defined as meaning both general agreement, and the process of getting to such agreement. Consensus decision-making is thus concerned primarily with that process.

Objectives[]

As a decision-making process, consensus decision-making aims to be:

- Inclusive: As many stakeholders as possible should be involved in the consensus decision-making process.

- Participatory: The consensus process should actively solicit the input and participation of all decision-makers.[1]

- Cooperative: Participants in an effective consensus process should strive to reach the best possible decision for the group and all of its members, rather than opt to pursue a majority opinion, potentially to the detriment of a minority.[1]

- Egalitarian: All members of a consensus decision-making body should be afforded, as much as possible, equal input into the process. All members have the opportunity to present, amend and veto or "block" proposals.

- Solution-oriented: An effective consensus decision-making body strives to emphasize common agreement over differences and reach effective decisions using compromise and other techniques to avoid or resolve mutually-exclusive positions within the group.

- Most Logical*: This happens when a solution appears to be impossible to execute because of the lack of support and cooperation.[2]

Alternative to majority rule[]

Proponents of consensus decision-making view procedures that use majority rule as undesirable for several reasons.

Majority voting is regarded as competitive, rather than cooperative, framing decision-making in a win/lose dichotomy that ignores the possibility of compromise or other mutually beneficial solutions.[3] On the other hand, some voting theorists have argued that majority rule leads to better deliberation practice than the alternatives, because it requires each member of the group to make arguments that appeal to at least half the participants and it encourages coalition-building.[4] Additionally, proponents of consensus argue that majority rule can lead to a 'tyranny of the majority'. However, voting theorists note that majority rule may actually prevent tyranny of the majority, in part because it maximizes the potential for a minority to form a coalition that can overturn an unsatisfactory decision.[5]

Advocates of consensus would assert that a majority decision reduces the commitment of each individual decision-maker to the decision. Members of a minority position may feel less commitment to a majority decision, and even majority voters who may have taken their positions along party or bloc lines may have a sense of reduced responsibility for the ultimate decision. The result of this reduced commitment, according to many consensus proponents, is potentially less willingness to defend or act upon the decision. Most Logical: This happens when a solution appears to be impossible to execute because of the lack of support and cooperation.

Process[]

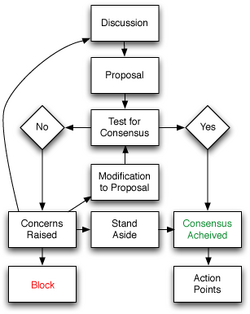

Flowchart of basic consensus decision-making process.

Since the consensus decision-making process is not as formalized as others (see Roberts Rules of Order), the practical details of its implementation vary from group to group. However, there is a core set of procedures which is common to most implementations of consensus decision-making.[6][7][8]

Once an agenda for discussion has been set and, optionally, the ground rules for the meeting have been agreed upon, each item of the agenda is addressed in turn. Typically, each decision arising from an agenda item follows through a simple structure:

- Discussion of the item: The item is discussed with the goal of identifying opinions and information on the topic at hand. The general direction of the group and potential proposals for action are often identified during the discussion.

- Formation of a proposal: Based on the discussion a formal decision proposal on the issue is presented to the group.

- Call for consensus: The facilitator of the decision-making body calls for consensus on the proposal. Each member of the group usually must actively state their agreement with the proposal, often by using a hand gesture or raising a colored card, to avoid the group interpreting silence or inaction as agreement.

- Identification and addressing of concerns: If consensus is not achieved, each dissenter presents his or her concerns on the proposal, potentially starting another round of discussion to address or clarify the concern.

- Modification of the proposal: The proposal is amended, re-phrased or ridered in an attempt to address the concerns of the decision-makers. The process then returns to the call for consensus and the cycle is repeated until a satisfactory decision is made.

Roles[]

The consensus decision-making process often has several roles which are designed to make the process run more effectively. Although the name and nature of these roles varies from group to group, the most common are the facilitator, a timekeeper, an empath and a secretary or notes taker. Not all decision-making bodies use all of these roles, although the facilitator position is almost always filled, and some groups use supplementary roles, such as a Devil's advocate or greeter. Some decision-making bodies opt to rotate these roles through the group members in order to build the experience and skills of the participants, and prevent any perceived concentration of power.[6]

The common roles in a consensus meeting are:

- Facilitator: As the name implies, the role of the facilitator is to help make the process of reaching a consensus decision easier. Facilitators accept responsibility for moving through the agenda on time; ensuring the group adheres to the mutually agreed-upon mechanics of the consensus process; and, if necessary, suggesting alternate or additional discussion or decision-making techniques, such as go-arounds, break-out groups or role-playing.[9][10] Some consensus groups use two co-facilitators. Shared facilitation is often adopted to diffuse the perceived power of the facilitator and create a system whereby a co-facilitator can pass off facilitation duties if he or she becomes more personally engaged in a debate.[11]

- Timekeeper: The purpose of the timekeeper is to ensure the decision-making body keeps to the schedule set in the agenda. Effective timekeepers use a variety of techniques to ensure the meeting runs on time including: giving frequent time updates, ample warning of short time, and keeping individual speakers from taking an excessive amount of time.[6]

- Empath or 'Vibe Watch': The empath, or 'vibe watch' as the position is sometimes called, is charged with monitoring the 'emotional climate' of the meeting, taking note of the body language and other non-verbal cues of the participants. Defusing potential emotional conflicts, maintaining a climate free of intimidation and being aware of potentially destructive power dynamics, such as sexism or racism within the decision-making body, are the primary responsibilities of the empath.[9]

- Note taker: The role of the notes taker or secretary is to document the decisions, discussion and action points of the decision-making body.

Non-unanimous consensus[]

Healthy consensus decision-making processes usually encourage and out dissent early, maximizing the chance of accommodating the views of all minorities. Since unanimity may be difficult to achieve, especially in large groups, or unanimity may be the result of coercion, fear, undue persuasive power or eloquence, inability to comprehend alternatives, or plain impatience with the process of debate, consensus decision making bodies may use an alternative benchmark of consensus. These include the following:

- Unanimity minus one (or U-1), requires all delegates but one to support the decision. The individual dissenter cannot block the decision although he or she may be able to prolong debate (e.g. via a filibuster). The dissenter may be the ongoing monitor of the implications of the decision, and their opinion of the outcome of the decision may be solicited at some future time. Betting markets in particular rely on the input of such lone dissenters. A lone bettor against the odds profits when his or her prediction of the outcomes proves to be better than that of the majority. This disciplines the market's odds.

- Unanimity minus two (or U-2), does not permit two individual delegates to block a decision and tends to curtail debate with a lone dissenter more quickly. Dissenting pairs can present alternate views of what is wrong with the decision under consideration. Pairs of delegates can be empowered to find the common ground that will enable them to convince a third, decision-blocking, decision-maker to join them. If the pair are unable to convince a third party to join them, typically within a set time, their arguments are deemed to be unconvincing.

- Unanimity minus three, (or U-3), and other such systems recognize the ability of four or more delegates to actively block a decision. U-3 and lesser degrees of unanimity are usually lumped in with statistical measures of agreement, such as: 80%, mean plus one sigma, two-thirds, or majority levels of agreement. Such measures usually do not fit within the definition of consensus.

- Rough Consensus is a process with no specific rule for "how much is enough." Rather, the question of consensus is left to the judgment of the group chair (an example is the IETF working group, discussed below). While this makes it more difficult for a small number of disruptors to block a decision, it puts increased responsibility on the chair, and may lead to divisive debates about whether rough consensus has in fact been correctly identified.

Dissent[]

Although the consensus decision-making process should, ideally, identify and address concerns and reservations early, proposals do not always garner full consensus from the decision-making body. When a call for consensus on a motion is made, a dissenting delegate has one of three options:

- Declare reservations: Group members who are willing to let a motion pass but desire to register their concerns with the group may choose "declare reservations." If there are significant reservations about a motion, the decision-making body may choose to modify or re-word the proposal.[12]

- Stand aside: A "stand aside" may be registered by a group member who has a "serious personal disagreement" with a proposal, but is willing to let the motion pass. Although stand asides do not halt a motion, it is often regarded as a strong "nay vote" and the concerns of group members standing aside are usually addressed by modifications to the proposal. Stand asides may also be registered by users who feel they are incapable of adequately understanding or participating in the proposal.[13][14][15]

- Block: Any group member may "block" a proposal. In most models, a single block is sufficient to stop a proposal, although some measures of consensus may require more than one block (see previous section, "Non-unanimous or modified consensus" ). Blocks are generally considered to be an extreme measure, only used when a member feels a proposal "endanger[s] the organization or its participants, or violate[s] the mission of the organization" (i.e., a principled objection). In some consensus models, a group member opposing a proposal must work with its proponents to find a solution that will work for everyone.Cite error: The opening

<ref>tag is malformed or has a bad name[16]

Criticisms[]

Critics of consensus decision-making often observe that the process, while potentially effective for small groups of motivated or trained individuals with a sufficiently high degree of affinity, has a number of possible shortcomings, notably

- Preservation of the Status quo: In decision-making bodies that use formal consensus, the ability of individuals or small minorities to block agreement gives an enormous advantage to anyone who supports the existing state of affairs. This can mean that a specific state of affairs can continue to exist in an organization long after a majority of members would like it to change. [17]

- Susceptibility to disruption: Giving the right to block proposals to all group members may result in the group becoming hostage to an inflexible minority or individual. Furthermore, "opposing such obstructive behavior [can be] construed as an attack on freedom of speech and in turn [harden] resolve on the part of the individual to defend his or her position."[18] As a result, consensus decision-making has the potential to reward the least accommodating group members while punishing the most accommodating.

- Abilene paradox: Consensus decision-making is susceptible to all forms of groupthink, the most dramatic being the Abilene paradox. In the Abilene paradox, a group can unanimously agree on a course of action that no individual member of the group desires because no one individual is willing to go against the perceived will of the decision-making body.[19]

- Time Consuming: Since consensus decision-making focuses on discussion and seeks the input of all participants, it can be a time-consuming process. This is a potential liability in situations where decisions need to be made speedily or where it is not possible to canvass the opinions of all delegates in a reasonable period of time. Additionally, the time commitment required to engage in the consensus decision-making process can sometimes act as a barrier to participation for individuals unable or unwilling to make the commitment.[20]

Historical examples[]

Perhaps the oldest example of consensus decision-making is the Iroquois Confederacy Grand Council, or Haudenosaunee, who have traditionally used consensus in decision-making,[21][22] potentially as early as 1142.[23] Other examples of consensus decision-making amongst indigenous people can be found such as amongst the bushmen, although they are often ignored in Eurocentric histories.[24] Although the modern popularity of consensus decision-making in Western society dates from the women's liberation movement[25] and anti-nuclear movement[26] of the 1970s, the origins of formal consensus can be traced significantly farther back.[27]

The most notable of early Western consensus practitioners are the Religious Society of Friends, or Quakers, who adopted the technique as early as the 17th century. The Anabaptists, or Mennonites, too, have a history of using consensus decision-making[28] and some believe Anabaptists practiced consensus as early as the Martyrs' Synod of 1527.[27] Some Christians trace consensus decision-making back to the Bible. The Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia references, in particular, Acts 15[29] as an example of consensus in the New Testament.

Models[]

Quaker model[]

Quaker-based consensus[30] is effective because it puts in place a simple, time-tested structure that moves a group towards unity. The Quaker model has been employed in a variety of secular settings. The process allows for individual voices to be heard while providing a mechanism for dealing with disagreements.[31][32]

The following aspects of the Quaker model can be effectively applied in any consensus decision-making process:

- Multiple concerns and information are shared until the sense of the group is clear.

- Discussion involves active listening and sharing information.

- Norms limit number of times one asks to speak to ensure that each speaker is fully heard.

- Ideas and solutions belong to the group; no names are recorded.

- Differences are resolved by discussion. The facilitator ("clerk" or "convenor" in the Quaker model) identifies areas of agreement and names disagreements to push discussion deeper.

- The facilitator articulates the sense of the discussion, asks if there are other concerns, and proposes a "minute" of the decision.

- The group as a whole is responsible for the decision and the decision belongs to the group.

- The facilitator can discern if one who is not uniting with the decision is acting without concern for the group or in selfish interest.

- Dissenters' perspectives are embraced.[30]

Key components of Quaker-based consensus include a belief in a common humanity and the ability to decide together. The goal is "unity, not unanimity." Ensuring that group members speak only once until others are heard encourages a diversity of thought. The facilitator is understood as serving the group rather than acting as person-in-charge.[33] In the Quaker model, as with other consensus decision-making processes, by articulating the emerging consensus, members can be clear on the decision, and, as their views have been taken into account, will be likely to support it.[34]

IETF rough consensus model[]

In the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), decisions are assumed to be taken by "rough consensus."[35] The IETF has studiously refrained from defining a mechanical method for verifying such consensus, apparently in the belief that any such codification will lead to attempts to "game the system." Instead, a working group (WG) chair or BoF chair is supposed to articulate the "sense of the group."

One tradition in support of rough consensus is the tradition of humming rather than (countable) hand-raising; this allows a group to quickly tell the difference between "one or two objectors" or a "sharply divided community", without making it easy to slip into "majority rule".[36]

Much of the business of the IETF is carried out on mailing lists, where all parties can speak their view at all times.

Other modern examples[]

The ISO process for adopting new standards is called consensus-based decision making[37], even though in practice, it is a complex voting process with significant supermajorities needed for agreement.[38]

Tools and methods[]

Colored cards[]

Some consensus decision-making bodies use a system of colored cards to speed up and ease the consensus process. Most often, each member is given a set of three colored cards: red, yellow and green. The cards can be raised during the process to indicate the member's input. Cards can be used during the discussion phase as well as during a call for consensus. The cards have different meanings depending on the phase in which they are used.Cite error: The opening <ref> tag is malformed or has a bad name[39] The meaning of the colors are:

- Red: During discussion, a red card is used to indicate a point of process or a breach of the agreed upon procedures. Identifying offtopic discussions, speakers going over allowed time limits or other breaks in the process are uses for the red card. During a call for consensus, the red card indicates the member's opposition (usually a "principled objection") to the proposal at hand. When a member, or members, use a red card, it becomes their responsibility to work with the proposing committee to come up with a solution that will work for everyone.

- Yellow: In the discussion phase, the yellow card is used to indicate a member's ability to clarify a point being discussed or answer a question being posed. Yellow is used during a call for consensus to register a stand aside to the proposal or to formally state any reservations.

- Green: A group member can use a green card during discussion to be added to the speakers list. During a call for consensus, the green card indicates consent.

Some decision-making bodies use a modified version of the colored card system with additional colors, such as orange to indicate a non-blocking reservation stronger than a stand-aside.[40]

Hand signals[]

Hand signals are often used by consensus decision-making bodies as a way for group members to nonverbally indicate their opinions or positions. Although the nature and meaning of individual gestures varies from group to group, there is a widely-adopted core set of hand signals. These include: wiggling of the fingers on both hands, a gesture sometimes referred to as "twinkling", to indicate agreement; raising a fist or crossing both forearms with hands in fists to indicate a block or strong disagreement; and making a "T" shape with both hands, the "time out" gesture, to call attention to a point of process or order.[10][41][42] One common set of hand signals is called the "Fist-to-Five" or "Fist-of-Five". In this method each member of the group can hold up a fist to indicate blocking consensus, one finger to suggest changes, two fingers to discuss minor issues, three fingers to indicate willingness to let issue pass without further discussion, four fingers to affirm the decision as a good idea, and five fingers to volunteer to take a lead in implementing the decision. [43]

See also[]

- Anarchism

- Consensus democracy

- Consensus government

- Decision making

- Facilitation

- Majority rule

- Sociocracy

- Supermajority

Notes[]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Rob Sandelin. Consensus Basics, Ingredients of successful consensus process. (HTML) Northwest Intentional Communities Association guide to consensus. Northwest Intentional Communities Association. URL accessed on 2007-01-17.

- ↑ Dressler, L. (2006). Consensus Through Conversation How to Achieve High-Commitment decisions.Berkeley, CA:Berrett-Koehler.

- ↑ Friedrich Degenhardt. Consensus: a colourful farewell to majority rule. (HTML) World Council of Churches. URL accessed on 2007-01-17.

- ↑ McGann, Anthony J. The Logic of Democracy: Reconciling, Equality, Deliberation, and Minority Protection. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. 2006. ISBN 0-472-06949-7.

- ↑ Anthony J. McGann. The Tyranny of the Supermajority: How Majority Rule Protects Majorities. (PDF) Center for the Study of Democracy. URL accessed on 2008-06-09.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 C.T. Lawrence Butler, Amy Rothstein. On Conflict and Consensus. (HTML) Food Not Bombs Publishing. URL accessed on 2007-01-17.

- ↑ What is Consensus?. (HTML) The Common Place. URL accessed on 2007-01-17.

- ↑ The Process. (HTML) Consensus Decision Making. Seeds for Change. URL accessed on 2007-01-17.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Sheila Kerrigan (2004). How To Use a Consensus Process To Make Decisions. (HTML) Community Arts Network. URL accessed on 2007-01-17.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Lori Waller. Guides: Meeting Facilitation. (HTML) The Otesha Project. URL accessed on 2007-01-17.

- ↑ Berit Lakey (1975). Meeting Facilitation --The No-Magic Method. (HTML) Network Service Collaboration. URL accessed on 2007-01-17.

- ↑ Richard Bruneau (2003). If Agreement Cannot Be Reached. (DOC) Participatory Decision-Making in a Cross-Cultural Context. Canada World Youth. URL accessed on 2007-01-17.

- ↑ Consensus Development Project (1998). FRONTIER: A New Definition. (HTML) Frontier Education Center. URL accessed on 2007-01-17.

- ↑ Rachel Williams, Andrew McLeod (2006). Introduction to Consensus Decision Making. (PDF) Cooperative Starter Series. Northwest Cooperative Development Center. URL accessed on 2007-01-17.

- ↑ Dorcas, Ellyntari. Amazing Graces' Guide to Consensus Process. (HTML) URL accessed on 2007-01-17.

- ↑ The Consensus Decision Process in Cohousing. (HTML) Canadian Cohousing Network. URL accessed on 2007-01-28.

- ↑ The Common Wheel Collective (2002). Introduction to Consensus. (HTML) The Collective Book on Collective Process. URL accessed on 2007-01-17.

- ↑ Alan McCluskey. Consensus building and verbal desperados. (HTML) URL accessed on 2007-01-17.

- ↑ Harvey, Jerry B. (Summer 1974). The Abilene Paradox and other Meditations on Management. Organizational Dynamics 3 (1): 63.

- ↑ Consensus Team Decision Making. (HTML) Strategic Leadership and Decision Making. National Defense University. URL accessed on 2007-01-17.

- ↑ How Does the Grand Council Work?. Great Law of Peace. URL accessed on 2007-01-17.

- ↑ M. Paul Keesler (2004). League of the Iroquois. (HTML) Mohawk - Discovering the Valley of the Crystals. URL accessed on 2007-01-18.

- ↑ Bruce E. Johansen (1995). Dating the Iroquois Confederacy. (HTML) Akwesasne Notes. URL accessed on 2007-01-17.

- ↑ United Nations (2002). Consensus Tradition can Contribute to Conflict Resolution, Secretary-General Says in Indigenous People's Day Message. Press release. Retrieved on 2007-01-17.

- ↑ David Graeber, Andrej Grubacic. Anarchism, Or The Revolutionary Movement Of The Twenty-first Century. (HTML) ZNet. URL accessed on 2007-01-17.

- ↑ Sanderson Beck (2003). Anti-Nuclear Protests. (HTML) Sanderson Beck. URL accessed on 2007-01-17.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Ethan Mitchell. Participation in Unanimous Decision-Making: The New England Monthly Meetings of Friends. (HTML) Philica. URL accessed on 2007-01-17.

- ↑ Abe J. Dueck (1990). Church Leadership: A Historical Perspective. (HTML) Direction. URL accessed on 2007-01-17.

- ↑ Ralph A Lebold (1989). Consensus. (HTML) Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. URL accessed on 2007-01-17.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Quaker Foundations of Leadership (1999). A Comparison of Quaker-based Consensus and Robert's Rules of Order. Richmond, Indiana: Earlham College. Retrieved on 2009-03-01.

- ↑ Woodrow, P. (1999). "Building Consensus Among Multiple Parties: The Experience of the Grand Canyon Visibility Transport Commission." Kellogg-Earlham Program in Quaker Foundations of Leadership. Retrieved on 2009-03-01.

- ↑ Berry, F. and M. Snyder (1999). "Notes prepared for Round table: Teaching Consensus-building in the Classroom." National Conference on Teaching Public Administration, Colorado Springs, Colorado, March 1998. Retrieved on 2009-03-01.

- ↑ Quaker Foundations of Leadership (1999). "Our Distinctive Approach. Richmond, Indiana: Earlham College. Retrieved on 2009-03-01.

- ↑ Maine.gov. What is a Consensus Process? State of Maine Best Practices. Retrieved on: 2009-03-01.

- ↑ RFC 2418. "IETF Working Group Guidelines and Procedures."

- ↑ (2006). The Tao of IETF: A Novice's Guide to the Internet Engineering Task Force. (HTML) The Internet Society. URL accessed on 2007-01-17.

- ↑ International Organization for Standardization (September 28, 2000) Report of the ISO Secretary-General to the ISO General Assembly. Retrieved on: April 6, 2008

- ↑ Andrew Updegrove. The ISO/IEC Voting Process on OOXML Explained (and What Happens Next). URL accessed on 2008-09-13.

- ↑ The Consensus Decision Process in Cohousing. (HTML) Canadian Cohousing Network. URL accessed on 2007-01-28.

- ↑ Color Cards. (HTML) Mosaic Commons. URL accessed on 2007-01-17.

- ↑ Jan H, Erikk, Hester, Ralf, Pinda, Anissa and Paxus. A Handbook for Direct Democracy and the Consensus Decision Process. (PDF) Zhaba Facilitators Collective. URL accessed on 2007-01-18.

- ↑ Hand Signals. (PDF) Seeds for Change. URL accessed on 2007-01-18.

- ↑ Guide for Facilitators: Fist-to-Five Consensus-Building. (HTML) URL accessed on 2008-02-04.

External links[]

- Template:Spunk

- "Consensus Decision Making" -- Seeds for Change

- "On Conflict and Consensus." -- C. T. Lawrence Butler and Amy Rothstein (1987) Food Not Bombs Publishing. Also available in .pdf format

- "The Formal Consensus Website" -- Based on work by C. T. Lawrence Butler and Amy Rothstein

- "A Manual for Meetings, Revised Edition" -- The Uniting Church in Australia

- "Papers on Cooperative Decision-Making" -- Randy Schutt

- "One Vote for Democracy" -- Ulli Diemer

- "Some Materials on Consensus." Quaker Foundations of Leadership, 1999. Richmond, Indiana: Earlham College.

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia (view authors). |