Assessment |

Biopsychology |

Comparative |

Cognitive |

Developmental |

Language |

Individual differences |

Personality |

Philosophy |

Social |

Methods |

Statistics |

Clinical |

Educational |

Industrial |

Professional items |

World psychology |

Clinical: Approaches · Group therapy · Techniques · Types of problem · Areas of specialism · Taxonomies · Therapeutic issues · Modes of delivery · Model translation project · Personal experiences ·

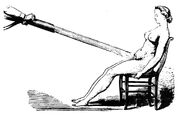

Water massages as a treatment for hysteria c. 1860.

In Western medicine, female hysteria was an incorrectly diagnosed medical condition that is not currently acknowledged by the medical community. It was a popular diagnosis in the Victorian era for a wide array of symptoms including faintness, nervousness, insomnia, fluid retention, heaviness in abdomen, muscle spasm, shortness of breath, irritability, loss of appetite for food or sex, and a ”tendency to cause trouble”.[1]

Patients diagnosed with female hysteria would undergo "pelvic massage" — manual stimulation of the woman's genitals by the doctor to "hysterical paroxysm", which is now recognized as orgasm.

Early history[]

Hysteria's history can be traced back to ancient times; it was described by both the ancient physician Hippocrates and Plato, although it was previously recorded in Egyptian papyri. An ancient Greek myth tells of the uterus wandering throughout a woman’s body, strangling the victim as it reaches the chest and causing disease. This theory is the source of the name, which stems from the Greek word for uterus, hystera.

A prominent physician from the second century, Galen, wrote that hysteria was a disease caused by sexual deprivation in particularly passionate women: hysteria was noted quite often in virgins, nuns, widows, and occasionally married women. The prescription in medieval and renaissance medicine was intercourse if married, marriage if single, or massage by a midwife as a last recourse.[1]

Victorian era[]

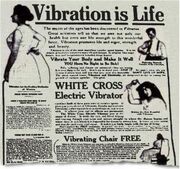

Advertisement from 1910.

A physician in 1859 claimed that a quarter of all women suffered from hysteria, which is reasonable considering that one physician cataloged 75 pages of possible symptoms of hysteria and called the list incomplete[2]; almost any ailment could fit the diagnosis. Physicians thought that the stresses associated with modern life caused civilized women to be both more susceptible to nervous disorders and to develop faulty reproductive tracts.[3] In America, such disorders in women reaffirmed that the United States was on par with Europe; one American physician expressed pleasure that the country was ”catching up” to Europe in the prevalence of hysteria.[2]

Rachael P. Maines, author of The Technology of Orgasm: "Hysteria," the Vibrator, and Women's Sexual Satisfaction, has observed that such cases were quite profitable for physicians, since the patients were at no risk of death but needed constant treatment. The only problem was that physicians did not enjoy the tedious task of massage: the technique was difficult for a physician to master and took hours to achieve ”hysterical paroxysm”. Referral to midwives, which had been common practice, meant a loss of business for the physician.[1]

A solution was the invention of massage devices, which shortened treatment from hours to minutes, removing the need for midwives and increasing a physician’s treatment capacity. Already at the turn of the century, hydrotherapy devices were available at Bath, and by the mid-nineteenth century, they were popular at many high-profile bathing resorts across Europe and in America. By 1870 a clockwork driven vibrator was available for physicians, and in 1873 the first electromechanical vibrator was used at an asylum in France for the treatment of hysteria.

While physicians of the period acknowledged that the disorder stemmed from sexual dissatisfaction, they seemed unaware of or unwilling to admit the sexual purposes of the devices used to treat it. In fact, the introduction of the speculum was far more controversial than that of the vibrator[1], perhaps because of it's phallic nature.

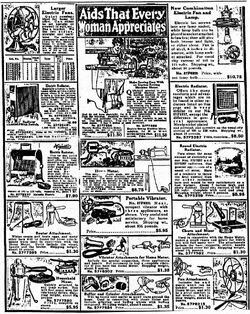

A 1918 Sears, Roebuck and Co. ad with several models of vibrators.

By the turn of the century, the spread of home electricity brought the vibrator to the consumer market. The appeal of cheaper treatment in the privacy of one’s own home understandably made the vibrator a popular early home appliance. In fact, the electric home vibrator was on the market before many other home appliance ’essentials’: nine years before the electric vacuum cleaner and ten years before the electric iron.[1] A page from a Sears catalog of home electrical appliances from 1918 includes a portable vibrator with attachments, billed as ”Very useful and satisfactory for home service.”

Theories on Victorian hysteria[]

It has been argued that a major theme of the nineteenth century is the conflict between sex as a reproductive act and an erotic act.[4] Although the icon of the period, Queen Victoria, had a large family, fertility rates actually declined over the course of the century. As fertility rates declined, the reproductive purpose of sex became less central. Much of the medical and marital advice literature of the period prominently featured the passionless woman as an ideal. Such a woman would only engage in sex in order to reproduce, as it holds no other allure for her. Tying sex to procreation through this rhetoric could be argued to serve many social goals: it could be used by both men and women to gain power in society, it shapes the fundamental social structure, and it creates a rhetoric against contraception, which will in turn influence fertility rates. It also led to rising sexual dissatisfaction in women, fuelling the increased demand for treatment of hysteria.

Disappearance of hysteria as a medical diagnosis[]

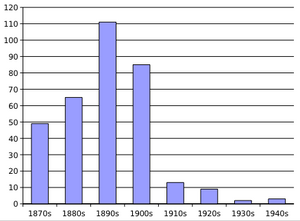

Number of French psychiatric theses on hysteria.

Over the course of the early twentieth century, cases of hysteria sharply declined and today female hysteria is no longer a recognized illness. Many reasons are behind its decline: many medical authors claim that the decline is due to laypeople gaining a greater understanding of the psychology behind conversion disorders such as hysteria, and it therefore no longer gets the desired response from society.[5]

It has also been argued that all that changed was where the disease was placed by physicians. With so many possible symptoms, hysteria was always a catchall diagnosis where any unidentifiable ailment could be assigned, and so, as diagnostic techniques improved, the number of cases were pared down until nothing was left. Many cases that would have been labelled hysteria were reclassified by Freud as anxiety neuroses.

Today different manifestations of hysteria is recognised amongst other things, schizophrenia, conversion disorder and anxiety attacks.

References[]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Rachel P. Maines (1999). The Technology of Orgasm: "Hysteria," the Vibrator, and Women's Sexual Satisfaction, Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801866464.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Laura Briggs (2000). The Race of Hysteria: "Overcivilization" and the "Savage" Woman in Late Nineteenth-Century Obsterics and Gynecology. American Quarterly 52: 246-73.

- ↑ Regina M. Morantz and Sue Zschoche (1980). Professionalism, Feminism, and Gender Roles: A Comparative Study of Nineteenth-Century Medical Therapeutics. The Journal of American History 67: 568-88.

- ↑ Estelle B. Freedman (1982). Sexuality in Nineteenth-Century America: Behavior, Ideology, and Politics. Reviews in American History 10: 196-215.

- ↑ Mark S. Micale (1993). On the "Disappearance" of Hysteria: A Study in the Clinical Deconstruction of a Diagnosis. Isis 84: 496-526.

See also[]

- Human female sexuality

Further reading[]

- Katrien Libbrecht (1995). Hysterical psychosis:a historical survey, London: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 156000181X.

- Mark S. Micale (1995). Approaching hysteria: disease and its interpretations, Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691037175.

- Niel Micklem (1996). The Nature of Hysteria, Routledge. ISBN 0415121868.

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia (view authors). |