m (Automatic delinking using popups) |

No edit summary |

||

| (15 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{PhilPsy}} |

{{PhilPsy}} |

||

| − | '''Epistemology''', from the [[Greek language|Greek]] words ''[[episteme]]'' (knowledge) and ''[[logos]]'' (word/speech) is the branch of [[philosophy]] that deals with the nature, origin and scope of [[knowledge]]. Historically, it has been one of the most investigated and most debated of all philosophical subjects. Much of this debate has focused on analysing the nature and variety of knowledge and how it relates to similar notions such as [[truth]] and [[belief]]. Much of this discussion concerns the justification of knowledge claims, that is the grounds on which one can claim to know a particular fact. |

||

| − | Not surprisingly, the way that knowledge claims are justified both leads to and depends on the general approach to philosophy one adopts. Thus, philosophers have developed a range of epistemological theories to accompany their general philosophical positions. More recent studies have re-written centuries-old assumptions, and the field of epistemology continues to be vibrant and dynamic. |

||

| + | [[Image:Classical-Definition-of-Kno.svg|thumb|250px|right| According to [[Plato]], knowledge is a subset of that which is both true and believed]]'''Epistemology''' or '''theory of knowledge''' is the branch of [[philosophy]] that studies the nature and scope of [[knowledge]] and [[belief]]. The term "epistemology" is based on the Greek words "''{{polytonic|ἐπιστήμη}} or episteme''" (knowledge or science) and "''λόγος or [[logos]]''" (account/explanation); it was introduced into English by the Scottish philosopher James Frederick Ferrier (1808-[[1864]]).<ref>[http://p2.www.britannica.com/ebc/article-9002832 "James Frederick Ferrier", Britannica Concise Encyclopedia]</ref> |

||

| − | == Defining knowledge == |

||

| − | === Justified true belief === |

||

| − | In Plato's dialogue the ''[[Theaetetus (Plato)|Theaetetus]]'', Socrates considers a number of definitions of knowledge. One of the prominent candidates is '''[[Theory of justification|justified]] [[truth|true]] [[belief]]'''. We know that for something to count as knowledge it must be true and be believed to be true (see section on defining belief in Epistemology, below). Socrates argues that this is insufficient; in addition one must have a ''reason'' or ''justification'' for that belief. |

||

| + | Epsistemological theories in philosophy are a ways of [[Philosophical analysis|analyzing]] the nature of knowledge and how it relates notions such as [[truth]], [[belief]], and [[Theory of justification|justification]]. It also deals with the means of production of knowledge, as well as skepticism about different knowledge claims. In other words, epistemology primarily addresses the following questions: "What is knowledge?", "How is knowledge acquired?", and "What do people know?". |

||

| − | One implication of this definition is that one cannot be said to "know" something just because one believes something that subsequently turns out to be true. An ill person with no medical training, but a generally optimistic attitude, might believe that she will recover from her illness quickly. But even if this belief turned out to be true, on the Theaetetus account, the patient did not '''know''' that she would get well because her belief lacked justification. |

||

| + | Psychologists have greatly contributed to elucidating the answer to the latter two questions making them the subject of empirical investigation rather than philosophical speculation. |

||

| − | Knowledge, therefore, is distinguished from true belief by its '''justification''', and much of epistemology is concerned with how true beliefs might be properly justified. This is sometimes referred to as the [[theory of justification]]. |

||

| + | There are many different topics, stances, and arguments in the field of epistemology. Recent psychological studies have dramatically challenged centuries-old assumptions, and the discipline therefore continues to be vibrant and dynamic. |

||

| − | The Theaetetus definition agrees with the common sense notion that we can believe things without knowing them. Whilst ''knowing'' p [[Logical conditional|entails]] that p is true, ''believing'' in p does not, since we can have false beliefs. It also implies that we believe everything that we know. That is, the things we know form a [[subset]] of the things we believe. |

||

| + | ==Defining knowledge== |

||

| − | For most of philosophical history, "knowledge" was taken to mean belief that was justified as true to an absolute certainty. Any less justified beliefs were called mere "probable opinion." This viewpoint still prevailed at least as late as [[Bertrand Russell]]'s early 20th century book ''The Problems of Philosophy''. In the decades that followed, however, the notion that the belief had to be justified ''to a certainty'' lost favour. |

||

| + | The first issue epistemology must address is the question of what knowledge is. This question is several millennia old, and among the most prominent in epistemology. |

||

| + | ===Distinguishing ''knowing that'' from ''knowing how''=== |

||

| − | === Gettier cases and contemporary definitions of knowledge=== |

||

| + | In this article, and in epistemology in general, the kind of knowledge usually discussed is [[propositional knowledge]], also known as "knowledge-that" as opposed to "knowledge-how". For example: in mathematics, it is knowing ''that'' 2 + 2 = 4, but there is also knowing ''how'' to add two numbers. Or, one knows ''how'' to ride a bicycle and one knows ''that'' a bicycle has two wheels. |

||

| − | {{main|Gettier problem}} |

||

| + | Philosophers thus distinguish between ''[[theoretical reason]]'' (knowing that) and ''[[practical reason]]'' (knowing how), with epistemology being interested primarily in theoretical knowledge. This distinction is recognised linguistically in many languages but not in English. In French (as well as in Portuguese and Spanish), for example, to know a person is 'connaître' ('conhecer' / 'conocer'), whereas to know how to do something is 'savoir' ('saber' in both Portuguese and Spanish). In Italian the verbs are respectively 'conoscere' and 'sapere' and the nouns for 'knowledge' are 'conoscenza' and 'sapienza'. In the German language, it is exemplified with the verbs "kennen" and "wissen." "Wissen" implies knowing as a fact, "kennen" implies knowing in the sense of being acqainted with and having a working knowledge of. But neither of those verbs do truly extend to the full meaning of the subject of epistemology. In German, there is also a verb derived from "kennen", namely ''"erkennen"'', which roughly implies knowledge in form of recognition or acknowledgment, strictly metaphorically. The verb itself implies a process: you have to go from one state to another: from a state of "not-''erkennen''" to a state of true ''erkennen''. This verb seems to be the most appropriate in terms of describing the "episteme" in one of the modern European languages. |

||

| − | In the 1960s, [[Edmund Gettier]] argued that there are situations in which a belief may be justified and true, and yet would not count as knowledge - overturning in a few short pages a theory that had been dominant for thousands of years. Although being a justified, true belief is ''necessary'' for a statement to count as knowledge, it is not, Gettier demonstrated, ''sufficient''. Gettier says that formulations of the following form are flawed: |

||

| + | ===Belief=== |

||

| − | S knows that P if and only if: |

||

| + | {{main|Belief}} |

||

| − | * P |

||

| + | Sometimes, when people say that they believe in something, what they mean is that they predict that it will prove to be useful or successful in some sense — perhaps someone might "believe in" his or her favorite [[football]] team. This is not the kind of belief usually addressed within epistemology. The kind that ''is'' dealt with, as such, is where "to believe something" just means to think that it is true — e.g., to believe that the sky is blue is to think that the proposition, "The sky is blue," is true. |

||

| − | * S believes that P, and |

||

| − | * S is justified in believing that P. |

||

| + | Knowledge implies belief. Consider the statement, "I know ''P'', but I don't believe that ''P'' is true." This statement is contradictory. To know ''P'' is, among other things, to believe that ''P'' is true, i.e. to believe in ''P''. (See the article on [[Moore's paradox]].) |

||

| − | This is because we can conceive of circumstances in which a person might have a good reason to believe a general proposition true, be correct, but not be correct for the reasons which she takes herself to be. Gettier gives the example of two persons, Smith and Jones, who are awaiting the results of their applications for the same job, both of whom have ten coins in their pockets. Smith has excellent reasons to believe that Jones will get the job and is furthermore correct in his belief that Jones has 10 coins in his pocket (he saw them counted just a moment before). From this he infers that ‘a person with ten coins in his pocket will get the job’. However, Smith doesn’t know that he himself also has 10 coins in his pocket. In fact, Smith is to get the job – his reasons to believe otherwise were excellent, but wrong. His belief that ‘a person with ten coins in his pocket will get the job’ satisfies all the above conditions, but still we would be hesitant to say that he knew what he thought he knew, because the reasons he took to justify his belief, while strong, were not the reasons which would have correctly justified his belief. (Which might have included the knowledge of ‘I have ten coins in my pocket’ and an overriding reason to believe that he would get the job). |

||

| + | ===Truth=== |

||

| − | Someone might want to say that, in fact, as far as they are concerned in the example given, Smith really does ‘know’ that ‘someone with ten coins in their pocket’ will get the job, but many people find this hard to accept. |

||

| + | {{Main|Truth}} |

||

| + | If someone believes something, he or she thinks that it is true, but he or she may be mistaken. This is not the case with knowledge. For example, suppose that Jeff thinks that a particular bridge is safe, and attempts to cross it; unfortunately, the bridge collapses under his weight. We might say that Jeff ''believed'' that the bridge was safe, but that his belief was mistaken. We would ''not'' accurately say that he ''knew'' that the bridge was safe, because plainly it was not. For something to count as knowledge, it must actually be true. |

||

| + | ==Justified true belief== |

||

| − | ====Responses to Gettier==== |

||

| + | {{main|Theaetetus (dialogue)}} |

||

| − | Gettier's article was published in 1963. Since then, there have been an enormous number of articles trying to provide an adequate definition of knowledge, several of which have been an attempt to supply a further fourth condition. Robert Nozick offers this formulation: |

||

| + | In [[Plato|Plato's]] dialogue ''[[Theaetetus (dialogue)|Theaetetus]]'', [[Socrates]] considers a number of theories as to what knowledge is, the last being that knowledge is true belief that has been "given an account of" — meaning explained or defined in some way. According to the theory that knowledge is justified true belief, in order to know that a given proposition is true, one must not only believe the relevant true proposition, but one must also have a good reason for doing so. One implication of this would be that no one would gain knowledge just by believing something that happened to be true. For example, an ill person with no medical training, but a generally optimistic attitude, might believe that she will recover from her illness quickly. Nevertheless, even if this belief turned out to be true, the patient would not have ''known'' that she would get well since her belief lacked justification. |

||

| − | S knows that P if and only if: |

||

| + | The [[definition]] of knowledge as justified true belief was widely accepted until the [[1960s]]. At this time, a paper written by the American philosopher [[Edmund Gettier]] provoked widespread discussion. |

||

| − | * P |

||

| − | * S believes that P |

||

| − | * If not P, S would not believe that P |

||

| − | * If P, S will believe that P |

||

| + | ===The Gettier problem=== |

||

| − | [[Simon Blackburn]] offers a critique of this formulation, in which he suggests that we do not want to accept as knowledge beliefs which, while they 'track the truth' (as Nozick's account requires), are not held for appropriate reasons. He says that 'we do not want to award the title of knowing something to someone who is only meeting the conditions through a defect, flaw, or failure, compared with someone else who is not meeting the conditions.' |

||

| + | {{main|Gettier problem}} |

||

| + | In 1963 [[Edmund Gettier]] called into question the theory of knowledge that had been dominant among philosophers for thousands of years<ref name=gettier> |

||

| − | In another response to Gettier, [[Richard Kirkham]] has argued that the failures to find an account of knowledge immune from counterexamples is because the only definition that could ever be immune to all such counterexamples is the original one that prevailed from ancient times through Russell: to qualify as an item of knowledge, a belief must not only be true and justified, the evidence for the belief must ''necessitate'' its truth. Though this seems to set a very high hurdle for truth, Kirkham notes that it doesn't exclude the possibility of rational belief altogether. |

||

| + | {{cite journal |

||

| + | |author = Gettier, Edmund |

||

| + | |year = 1963 |

||

| + | |title = Is Justified True Belief Knowledge? |

||

| + | |journal = Analysis |

||

| + | |volume = 23 |

||

| + | |pages =121-23 |

||

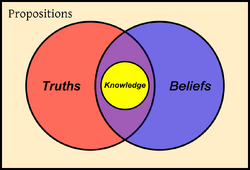

| + | }}</ref>. In a few pages, Gettier argued that there are situations in which one's belief may be justified and true, yet fail to count as knowledge. That is, Gettier contended that while it is necessary for knowledge of a proposition that one be justified in one's true belief in that proposition, it is not sufficient. As in the diagram above, a true proposition can be believed by an individual but still not fall within the "knowledge" category (purple region). |

||

| + | According to Gettier, there are certain circumstances in which one does not have knowledge, even when all of the above conditions are met. Gettier proposed two [[thought experiment]]s, which have come to be known as "Gettier cases", as [[counterexample]]s to the classical account of knowledge. One of the cases involves two men, Smith and Jones, who are awaiting the results of their applications for the same job. Each man has ten coins in his pocket. Smith has excellent reasons to believe that Jones will get the job and, furthermore, knows that Jones has ten coins in his pocket (he recently counted them). From this Smith infers, "the man who will get the job has ten coins in his pocket." However, Smith is unaware that he has ten coins in his own pocket. Furthermore, Smith, not Jones, is going to get the job. While Smith has strong evidence to believe that Jones will get the job, he is wrong. Smith has a justified true belief that a man with ten coins in his pocket will get the job; however, according to Gettier, Smith does not ''know'' that a man with ten coins in his pocket will get the job, because Smith's belief is "...true in virtue of the number of coins in ''Smith's'' pocket, while Smith does not know how many coins are in Smith's pocket, and bases his belief...on a count of the coins in Jones's pocket, whom he falsely believes to be the man who will get the job."(see <ref name = gettier/> p.122.) |

||

| − | Some of the proposed solutions involve factors external to the agent. These responses are known as theories of [[externalism]]. For example, one externalist response to the Gettier problem is to say that the justified, true belief must be caused (in the right sort of way) by the relevant facts. |

||

| + | ===Responses to Gettier=== |

||

| − | === Contemporary approaches === |

||

| + | The responses to Gettier have been varied. With respect to the example of Smith and his job, Smith really does know that someone with ten coins in his pocket will get the job. However, some may find this, as a claim to knowledge, counterintuitive. Usually, responses to Gettier have involved substantive attempts to provide a definition of knowledge different from the classical one, either by recasting knowledge as justified true belief with some additional fourth condition, or as something else altogether. |

||

| + | ====Infallibilism, indefeasibility==== |

||

| − | Much contemporary work in epistemology depends on the two categories: [[foundationalism]] and [[coherentism]]. |

||

| + | In one response to Gettier, the American philosopher [[Richard Kirkham]] has argued that the only definition of knowledge that could ever be immune to all counterexamples is the [[infallibilism|infallibilist]] one.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} To qualify as an item of knowledge, so the theory goes, a belief must not only be true and justified, the justification of the belief must ''necessitate'' its truth. In other words, the justification for the belief must be infallible. (See ''[[#Fallibilism|Fallibilism]]'', below, for more information.) |

||

| − | Recently, [[Susan Haack]] has attempted to fuse these two approaches into her doctrine of [[Foundherentism]], which accrues degrees of relative confidence to beliefs by mediating between the two approaches. She covers this in her book [[Evidence and Inquiry: Towards Reconstruction in Epistemology]]. [[Timothy Williamson]], in his book [[Knowledge and its Limits]], seeks to revert the traditional conceptual priority of belief to knowledge, instead seeing belief as dependent on knowledge |

||

| + | Yet another possible candidate for the fourth condition of knowledge is ''indefeasibility''. Defeasibility theory maintains that there should be no overriding or defeating truths for the reasons that justify one's belief. For example, suppose that person ''S'' believes they saw Tom Grabit steal a book from the library and uses this to justify the claim that Tom Grabit stole a book from the library. A possible defeater or overriding proposition for such a claim could be a true proposition like, "Tom Grabit's identical twin Sam is currently in the same town as Tom." So long as no defeaters of one's justification exist, a subject would be epistemically justified. |

||

| − | === Defining 'belief' in Epistemology === |

||

| − | [[Image:Classical-Definition-of-Kno.gif|frame|Knowledge is true and believed and ...]] |

||

| + | The Indian philosopher [[B K Matilal]] has drawn on the [[Navya-Nyaya]] [[fallibilism]] tradition to respond to the Gettier problem. |

||

| − | Sometimes, when people say they 'believe in' something, what they mean is that they predict that it will prove to be useful or successful in some sense - perhaps someone might 'believe in' his or her favourite football team. This is not what Epistemologists mean. |

||

| + | Nyaya theory distinguishes between ''know p'' and ''know that one knows p'' - these are different events, with different causal conditions. |

||

| + | The second level is a sort of implicit inference that usually follows immediately the episode of knowing p (knowledge ''simpliciter''). The Gettier |

||

| + | case is analyzed by referring to a view of [[Gangesha]] (13th c.), who takes any true belief to be knowledge; thus a true belief acquired through a wrong |

||

| + | route may just be regarded as knowledge simpliciter on this view. |

||

| + | The question of justification arises only at the second level, when one |

||

| + | considers the knowledgehood of the acquired belief. |

||

| + | Initially, there is lack of uncertainty, so it becomes a true belief. |

||

| + | But at the very next moment, when the hearer is about to embark upon the venture of knowing whether he ''knows p'', doubts may arise. "If, in |

||

| + | some Gettier-like cases, I am wrong in my inference about the |

||

| + | knowledgehood of the given occurrent belief (for the evidence may be |

||

| + | pseudo-evidence), then I am mistaken about the truth of my belief -- and |

||

| + | this is in accord with Nyaya fallibilism: not all knowledge-claims can be |

||

| + | sustained." |

||

| + | <ref name=Matilal> |

||

| + | {{cite book | |

||

| + | author = Bimal Krishna Matilal | |

||

| + | title = Perception: An essay on Classical Indian Theories of Knowledge | |

||

| + | publisher = Oxford India 2002 | |

||

| + | year = 1986 |

||

| + | }}The Gettier problem is dealt with in Chapter 4, ''Knowledge as a mental episode''. The thread continues in the next chapter |

||

| + | ''Knowing that one knows''. It is also discussed in Matilal's ''Word and the World'' p. 71-72. </ref> |

||

| + | ====Reliabilism==== |

||

| − | In the second sense of belief, to believe something just means to think that it is true. That is, to believe P is to do no more than to think, for whatever reason, that P is the case. The reason is that in order to ''know'' something, one must ''think that it is true'' - one must believe (in the second sense) it to be the case. |

||

| + | {{main|Reliabilism}} |

||

| + | Reliabilism is a theory advanced by philosophers such as [[Alvin Goldman]] according to which a belief is justified (or otherwise supported in such a way as to count towards knowledge) only if it is produced by processes that typically yield a sufficiently high ratio of true to false beliefs. In other words, as per its name, this theory states that a true belief counts as knowledge only if it is produced by a reliable belief-forming process. |

||

| − | Consider someone saying "I know that P, but I don't think P is true". The person making this utterance has, in a profound sense, contradicted himself. If one knows that P, then, amongst other things, one thinks that P is indeed true. If one thinks that P is true, then one believes P. (''See: [[Moore's paradox]]''.) |

||

| + | Reliabilism has been challenged by Gettier cases. A prominent such case is that of Henry and the barn façades. In the thought experiment, a man, Henry, is driving along and sees a number of buildings that resemble barns. Based on his perception of one of these, he concludes that he has just seen barns. While he has seen one, and the perception he based his belief on was of a real barn, all the other barn-like buildings he saw were façades. Theoretically, Henry doesn't know that he has seen a barn, despite both his belief that he has seen one being true and his belief being formed on the basis of a reliable process (i.e. his vision), since he only acquired his true belief by accident.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} |

||

| − | Knowledge is distinct from [[belief]] and [[opinion]]. If someone claims to believe something,he is claiming that he thinks that it is the [[truth]]. But of course, it ''might'' turn out that he was mistaken, and that what he thought was true was actually false. This is not the case with knowledge. For example, suppose that Jeff thinks that a particular bridge is safe, and attempts to cross it; unfortunately the bridge collapses under his weight. We might say that Jeff ''believed'' that the bridge was safe, but that his belief was mistaken. We would ''not'' say that he ''knew'' that the bridge was safe, because plainly it was not. For something to count as ''knowledge'', it must be true. |

||

| + | ====Other responses==== |

||

| − | Similarly, two people can ''believe'' things that are mutually contradictory, but they cannot ''know'' (unequivocally) things that are mutually contradictory. For example, Jeff can ''believe'' the bridge safe, while Jenny believes it unsafe. But Jeff cannot ''know'' the bridge is safe and Jenny cannot ''know'' that the bridge is unsafe simultaneously. Two people cannot ''know'' contradictory things. |

||

| + | The American philosopher [[Robert Nozick]] has offered the following definition of knowledge: |

||

| − | + | ''S'' knows that ''P'' if and only if: |

|

| + | * ''P''; |

||

| − | Suppose that [[Metasyntactic variable|Fred]] says to you: "The fastest [[swimming]] stroke is the [[front crawl]]. One performs the front crawl by oscillating the legs at the hip, and moving the arms in an approximately circular motion". Here, Fred has [[propositional knowledge]] of swimming and how to perform the front crawl. |

||

| + | * ''S'' believes that ''P''; |

||

| + | * if ''P'' were false, ''S'' would not believe that ''P''; |

||

| + | * if ''P'' is true, ''S'' will believe that ''P''. <ref name=Nozick> |

||

| + | {{cite book | |

||

| + | author = Robert Nozick | |

||

| + | title = Philosophical Explanations | |

||

| + | publisher = Harvard University Press | |

||

| + | year = 1981 |

||

| + | }}[[Philosophical Explanations]] Chapter 3 "Knowledge and Skepticism" I. Knowledge ''Conditions for Knowledge'' p. 172-178. </ref> |

||

| + | Nozick believed that the third subjunctive condition served to address cases of the sort described by Gettier. Nozick further claims this condition addresses a case of the sort described by [[D. M. Armstrong]]<ref name=Armstrong> |

||

| + | {{cite book | |

||

| + | author = D. M. Armstrong | |

||

| + | title = Belief, Truth and Knowledge | |

||

| + | publisher = Cambridge University Press | |

||

| + | year = 1973 |

||

| + | }}[[Philosophical Explanations]] Chapter 3 "Knowledge and Skepticism" I. Knowledge ''Conditions for Knowledge'' p. 172-178. </ref>: A father believes his son innocent of committing a particular crime, both because of faith in his son and (now) because he has seen presented in the courtroom a conclusive demonstration of his son's innocence. His belief via the method of the courtroom satisfies the four subjunctive conditions, but his faith-based belief does not. If his son were guilty, he would still believe him innocent, on the basis of faith in his son; this would violate the third subjunctive condition. |

||

| + | The British philosopher [[Simon Blackburn]] has criticized this formulation by suggesting that we do not want to accept as knowledge beliefs which, while they "track the truth" (as Nozick's account requires), are not held for appropriate reasons. He says that "we do not want to award the title of knowing something to someone who is only meeting the conditions through a defect, flaw, or failure, compared with someone else who is not meeting the conditions."{{Fact|date=February 2007}} |

||

| − | However, if Fred acquired this propositional knowledge from an [[encyclopedia]], he will not have acquired the [[skill]] of swimming: he has some propositional knowledge, but does not have any [[procedural knowledge]] or "know-how". In general, one can demonstrate know-how by performing the task in question, but it is harder to demonstrate propositional knowledge. [[Michael Polanyi]] popularised the term [[tacit knowledge]] to distinguish the ability to do something from the ability to describe how to do something. [[Gilbert Ryle]] had previously made a similar point in discussing the characteristics of [[intelligence (trait)|intelligence]]. His ideas are summed up in the [[aphorism]] "efficient practice precedes the theory of it". Someone with the ability to perform the appropriate moves is said to be able to swim, even if that person cannot precisely identify what it is he does in order to swim. This distinction is often traced back to [[Plato]], who used the term ''[[techne]]'' or ''skill'' for ''knowledge how'', and the term ''[[episteme]]'' for a more robust kind of knowledge in which claims can be true or false. |

||

| + | Finally, at least one philosopher, [[Timothy Williamson]], has advanced a theory of knowledge according to which knowledge is not justified true belief plus some extra condition(s). In his book ''[[Knowledge and its Limits]]'', Williamson argues that the concept of knowledge cannot be analyzed into a set of other concepts—instead, it is ''[[sui generis]]''. Thus, though knowledge requires justification, truth, and belief, the word "knowledge" can't be, according to Williamson's theory, accurately regarded as simply shorthand for "justified true belief". |

||

| − | == A priori versus a posteriori knowledge == |

||

| − | Western [[Philosophy|philosophers]] for centuries have distinguished between two kinds of knowledge: [[a priori]] and [[a posteriori]] knowledge. |

||

| + | ====Externalism and internalism==== |

||

| − | *'''A priori''' knowledge is knowledge gained or justified by [[reason]] alone, without the direct or indirect influence of any particular experience (here, ''experience'' usually means observation of the world through sense perception. See ''[[#Rationalism|Rationalism]]'', below, for clarification.) |

||

| + | {{main|Internalism and externalism}} |

||

| − | *'''A posteriori''' knowledge is any other sort of knowledge; that is, knowledge the attainment or justification of which requires reference to experience. This is also called [[empirical knowledge]]. |

||

| + | Part of the debate over the nature of knowledge is a debate between epistemological externalists on the one hand, and epistemological internalists on the other. |

||

| + | Externalists think that factors deemed "external", meaning outside of the psychological states of those who gain knowledge, can be conditions of knowledge. For example, an externalist response to the Gettier problem is to say that, in order for a justified, true belief to count as knowledge, it must be caused, in the right sort of way, by relevant facts. Such causation, to the extent that it is "outside" the mind, would count as an external, knowledge-yielding condition. Internalists, contrariwise, claim that all knowledge-yielding conditions are within the psychological states of those who gain knowledge. |

||

| + | ==Acquiring knowledge== |

||

| − | One of the fundamental questions in [[epistemology]] is whether there is any non-trivial a priori knowledge. Generally speaking [[continental rationalism|rationalists]] believe that there is, while [[empiricism|empiricists]] believe that all knowledge is ultimately derived from some kind of external experience. |

||

| + | The second question that will be dealt with is the question of how knowledge is acquired. This area of epistemology covers what is called "the regress problem", issues concerning epistemic distinctions such as that between experience and apriority as means of creating knowledge and that between synthesis and analysis as means of proof, and debates such as the one between empiricists and rationalists. |

||

| + | ===The regress problem=== |

||

| − | The fields of knowledge most often suggested as having a priori status are [[logic]] and [[mathematics]], which deal primarily with abstract, formal objects. |

||

| + | {{main|Regress argument}} |

||

| + | Suppose we make a point of asking for a justification for every belief. Any given justification will itself depend on another belief for its justification, so one can also reasonably ask for this to be justified, and so forth. This appears to lead to an infinite regress, with each belief justified by some further belief. The apparent impossibility of completing an infinite chain of reasoning is thought by some to support [[skepticism]]. The skeptic will argue that since no one can complete such a chain, ultimately no beliefs are justified and, therefore, no one knows anything. However, many epistemologists studying justification have attempted to argue for various types of chains of reasoning that can escape the regress problem. |

||

| + | Some philosophers, notably [[Peter Klein]] in his "''Human Knowledge and the Infinite Regress of Reasons''", have argued that it's not impossible for an infinite justificatory series to exist. This position is known as "[[infinitism]]". Infinitists typically take the infinite series to be merely potential, in the sense that an individual may have indefinitely many reasons available to him, without having consciously thought through all of these reasons. The individual need only have the ability to bring forth the relevant reasons when the need arises. This position is motivated in part by the desire to avoid what is seen as the arbitrariness and circularity of its chief competitors, foundationalism and coherentism. |

||

| − | Empiricists have traditionally denied that even these fields could be a priori knowledge. Two common arguments are that these sorts of knowledge can only be derived from experience (as [[John Stuart Mill]] argued), and that they do not constitute "real" knowledge (as [[David Hume]] argued). |

||

| + | [[Foundationalism|Foundationalists]] respond to the regress problem by claiming that some beliefs that support other beliefs do not themselves require justification by other beliefs. Sometimes, these beliefs, labeled "foundational", are characterized as beliefs that one is directly aware of the truth of, or as beliefs that are self-justifying, or as beliefs that are infallible. According to one particularly permissive form of foundationalism, a belief may count as foundational, in the sense that it may be presumed true until defeating evidence appears, as long as the belief seems to its believer to be true.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} Others have argued that a belief is justified if it is based on perception or certain ''a priori'' considerations. |

||

| − | == Justification == |

||

| − | Much of epistemology has been concerned with seeking ways to justify beliefs. |

||

| + | The chief criticism of foundationalism is that it allegedly leads to the arbitrary or unjustified acceptance of certain beliefs.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} |

||

| − | ===Irrationalism=== |

||

| − | Some approaches to justifying beliefs are not [[rationality|rational]] — that is, they reject the notion that justification must obey [[logic]] or reason. [[Nihilism]] started out as a materialistic political philosophy, but is sometimes redefined as the apparently absurd doctrine that there can be no justification for any claim — absurd because the doctrine implies that nihilism itself cannot be justified. |

||

| + | Another response to the regress problem is [[coherentism]], which is the rejection of the assumption that the regress proceeds according to a pattern of linear justification. The original coherentist model for chains of reasoning was circular.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} This model was broadly repudiated, for obvious reasons.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} Most [[coherentism|coherentists]] now hold that an individual belief is not justified circularly, but by the way it fits together (coheres) with the rest of the belief system of which it is a part.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} This theory has the advantage of avoiding the infinite regress without claiming special, possibly arbitrary status for some particular class of beliefs. Yet, since a system can be coherent while also being wrong, coherentists face the difficulty in ensuring that the whole system [[correspondence theory of truth|corresponds]] to reality. |

||

| − | One definition of contemporary ''[[Mysticism]]'' is the use of non-rational methods to arrive at beliefs and the acceptance of such beliefs as knowledge. For example, believing that something is true based on emotion may be regarded as epistemological mysticism. An instance of this may be when one bases one's belief in the existence of something merely on one's ''desire'' that it should exist. Another example might be the use of a daisy's petals and the phrase "he loves me / he loves me not" while they are plucked to determine whether Romeo returns Juliet's affections. The mysticism in this example would be the assumption that such a method has predictive or indicative powers without rational evidence of this (this does not necessarily lessen its importance as a symbolic tool in human thought). In both of these examples, belief is not justified through rational means. Mysticism need not be an intentional process: one may engage in mystical thought without realizing it. |

||

| + | There is also a position known as "[[foundherentism]]". [[Susan Haack]] is the philosopher who conceived it, and it is meant to be a unification of foundationalism and coherentism. One component of this theory is what is called the "analogy of the crossword puzzle". Whereas, say, infinists regard the regress of reasons as "shaped" like a single line, Susan Haack has argued that it is more like a crossword puzzle, with multiple lines mutually supporting each other.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} |

||

| − | Contemporary Mysticism should not be confused with ''traditional'' Mysticism, which is a spiritual practice in many Eastern religions. It is the practice of focusing thought that is important to traditional mysticism, rather than the content of the thought. One difficulty precident in many forms of mysticism is the ''suspension of disbelief'' as conflicting beliefs are said to interfere with the supernatural spiritual or mental abilities. This can be criticized as not solely suspending disbelief, but in requiring an irrational belief of the possibility of the promised potential outcomes. |

||

| + | ===A priori and a posteriori knowledge=== |

||

| − | === Rationality === |

||

| + | {{main|A priori and a posteriori (philosophy)}} |

||

| − | [[Philosophical scepticism|Philosophical skeptics]] maintain that much of what we typically take to be knowledge is not in fact knowledge. In contrast to mystics, most skeptics attempt to present [[logical argument]]s for their claims. |

||

| + | The critical philosophy of [[Immanuel Kant]] introduced a distinction between two kinds of knowledge: ''a priori'' and ''a posteriori''. The nature of this distinction has been disputed by various philosophers; however, the terms may be roughly defined as follows: |

||

| + | *''A priori'' knowledge is knowledge that is known independently of experience (that is, it is non-empirical). |

||

| − | For instance, the [[regress argument]] has it that one can ask for the justification for any belief. If that justification depends on another belief, one can also reasonably ask for the latter belief to be justified, and so forth. This appears to lead to an infinite regress, with each belief justified by some further belief. The apparent impossibility of completing an infinite chain of reasoning is thought by some to support skepticism. |

||

| + | *''A posteriori'' knowledge is knowledge that is known by experience (that is, it is empirical). |

||

| − | Some philosophers, notably [[Peter Klein]], have argued that it is not impossible to have an infinite series of reasons and that such an infinite series could explain how we have knowledge. This position is known as ''[[infinitism]]''. Infinitists typically take the infinite series to be merely potential, in the sense that an individual may have indefinitely many reasons ''available'' to him, without having consciously thought through all of these reasons. The individual need only have the ability to bring forth the relevant reasons when the need arises. This position is motivated in part by the desire to avoid skepticism. |

||

| + | ===Analytic/synthetic distinction=== |

||

| − | [[Foundationalism|Foundationalists]] respond to the regress argument by claiming that some beliefs that are fit to support other beliefs and knowledge do not themselves require justification. Sometimes these ''foundational'' beliefs are characterized as beliefs about what one is directly aware of, or as beliefs that are self-justifying, or as beliefs that are infallible. According to one particularly permissive form of foundationalism, a belief may count as foundational, in the sense that it may be presumed true until defeating evidence appears, as long as the belief ''appears'' to the subject to be true. |

||

| + | {{main|Analytic/synthetic distinction}} |

||

| + | Some propositions are such that we appear to be justified in believing them just so far as we understand their meaning. For example, consider, "My father's brother is my uncle." We seem to be justified in believing it to be true by virtue of our knowledge of what its terms mean. Philosophers call such propositions "analytic". Synthetic propositions, on the other hand, have distinct subjects and predicates. An example of a synthetic proposition would be, "My father's brother has black hair." [[Immanuel Kant|Kant]] held that all mathematical propositions are synthetic. |

||

| − | Another response to the regress problem is to reject the assumption that beliefs can only be justified by linear chains of reasoning. [[Coherentism]] holds that an individual belief is justified not by such linear reasoning but by the way the belief fits together ([[Truth#Coherence Theory|coheres]]) with the rest of one's belief system. This has the advantage of avoiding the infinite regress without claiming special status for some particular class of beliefs. But since a system can be coherent and yet still be wrong, coherentists face the difficulty of ensuring that the whole system [[correspondence theory of truth|corresponds]] in some way with reality. |

||

| + | Although the American philosopher [[W. V. O. Quine]], in his "[[Two Dogmas of Empiricism]]", famously challenged it, leading to its being taken to be less obviously real than it once seemed, it is still widely believed that there is a distinction between analysis and synthesis.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} |

||

| − | === Synthetic and analytic statements === |

||

| − | Some statements are such that they appear not to need any justification once one understands their [[meaning]]. For example, consider: ''my father's brother is my uncle''. This statement is true in virtue of the meaning of the terms it contains, and so it seems frivolous to ask for a justification for saying it is true. Philosophers call such statements ''analytic''. More technically, a statement is analytic if the concept in the predicate is included in the concept in the subject. In the example, the concept of uncle (the predicate) is included in the concept of being my father's brother (the subject). Not all analytic statements are as trivial as this example. [[mathematics|Mathematical]] statements are often taken to be analytic. |

||

| + | ===Specific theories of knowledge acquisition=== |

||

| − | Synthetic statements, on the other hand, have distinct subjects and [[predicate]]s. An example would be ''my father's brother is overweight''. |

||

| + | ====Empiricism==== |

||

| + | {{main|Empiricism}} |

||

| + | In philosophy generally, empiricism is a theory of knowledge emphasizing the role of experience, especially experience based on [[perception|perceptual observations]] by the five [[sense|senses]]. Certain forms treat all knowledge as empirical,{{Fact|date=February 2007}} while some regard disciplines such as [[mathematics]] and [[logic]] as exceptions.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} |

||

| + | {{sectstub}} |

||

| + | ====Rationalism==== |

||

| − | Although anticipated by [[David Hume]], this distinction was more clearly formulated by [[Immanuel Kant]], and later given a more formal shape by [[Frege]]. [[Wittgenstein]] noted in the ''[[Tractatus]]'' that analytic statements "express no thoughts", that is, that they tell us nothing new; although analytic statements do not require justification, they are singularly uninformative. [[W.V.O. Quine]], in his famous ''[[Two Dogmas of Empiricism]]'', challenged the legitimacy of the analytic-synthetic distinction altogether. |

||

| + | {{main|Rationalism}} |

||

| + | Rationalists believe that knowledge is primarily (at least in some areas) acquired by ''a priori'' processes or is [[innatism|innate]]—e.g., in the form of concepts not derived from experience. The relevant theoretical processes often go by the name "[[intuition]]".{{Fact|date=February 2007}} The relevant theoretical concepts may purportedly be part of the structure of the human [[mind]] (as in [[Kant]]'s theory of [[transcendental idealism]]), or they may be said to exist independently of the mind (as in Plato's [[theory of Forms]]). |

||

| + | The extent to which this innate human knowledge is emphasized over experience as a means to acquire knowledge varies from rationalist to rationalist. Some hold that knowledge of any kind can only be gained ''a priori'',{{Fact|date=February 2007}} while others claim that some knowledge can also be gained ''a posteriori''.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} Consequently, the borderline between rationalist epistemologies and others can be vague. |

||

| − | == Epistemological theories == |

||

| − | It is common for epistemological theories to avoid skepticism by adopting a foundationalist approach. To do this, they argue that certain types of statements have a special epistemological status — that of not needing to be justified. So it is possible to classify epistemological theories according to the type of statement that each argues has this special status. |

||

| − | === |

+ | ====Constructivism==== |

| + | {{main|Constructivist epistemology}} |

||

| − | [[empiricism|Empiricists]] claim knowledge is a product of human [[experience]]. Statements of observations take pride of place in empiricist theory. [[Naïve empiricism]] holds simply that our ideas and theories need to be tested against [[realism|reality]], and accepted or rejected on the basis of how well they ''correspond'' to ''observed facts''. The central problem for epistemology then becomes explaining this [[correspondence theory of truth|correspondence]]. |

||

| + | Constructivism is a view in philosophy according to which all knowledge is "constructed" in as much as it is contingent on convention, human perception, and social experience.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} It originated in sociology under the term "social constructionism" and has been given the name "constructivism" when referring to philosophical epistemology, though "constructionism" and "constructivism" are often used interchangeably.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} |

||

| + | ==What do people know?== |

||

| − | Empiricism is associated with [[science]]. While there can be little doubt about the effectiveness of science, there is much philosophical debate about how and why science works. The [[Scientific Method]] was once favoured as the reason for scientific success, but recent difficulties in the [[philosophy of science]] have led to a rise in [[coherentism]]. |

||

| + | The last question that will be dealt with is the question of what people know. At the heart of this area of study is [[skepticism]], with many approaches involved trying to disprove some particular form of it. |

||

| + | ===Skepticism=== |

||

| − | [[Empiricism]] is sometimes associated with a tradition called [[logical empiricism]], or [[positivism]], which places higher emphasis on ideas about reality rather than on experiences of reality. |

||

| + | {{main|Philosophical skepticism}} |

||

| + | Skepticism is related to the question of whether certain knowledge is possible. Skeptics argue that the belief in something does not necessarily justify an assertion of knowledge of it. In this skeptics oppose [[foundationalism]], which states that there have to be some basic beliefs that are justified without reference to others. The skeptical response to this can take several approaches. First, claiming that "basic beliefs" must exist amounts to the logical fallacy of [[argument from ignorance]] combined with the [[slippery slope]]. While a foundationalist would use [[Munchhausen-Trilemma]] as a justification for demanding the validity of basic beliefs, a skeptic would see no problem with admitting the result. |

||

| + | This skeptical approach is rarely taken to its pyrrhonean extreme by most practitioners. Several modifications have arisen over the years, including the following[http://www.earlham.edu/~peters/writing/skept.htm#fideism]: |

||

| − | === Idealism === |

||

| − | [[Idealism]] holds that what we refer to and perceive as the external world is in some way an artifice of the mind. Analytic statements (for example, mathematical truths), are held to be true without reference to the external world, and these are taken to be exemplary knowledge statements. [[George Berkeley]], [[Immanuel Kant]] and [[Georg Hegel]] held various idealist views. Idealism is itself a ''[[metaphysical]]'' thesis, but has important epistemological consequences. |

||

| + | {{sectstub}} |

||

| − | ==== Naïve realism ==== |

||

| − | [[Naïve realism]], sometimes called Common Sense realism, is the belief that there is a real external world, and that our perceptions are caused directly by that world. It has its foundation in [[Causality|causation]] in that an object being there causes us to see it. Thus, it follows, the world remains as it is when it is perceived - when it is not being perceived - ''a room is still there once we exit''. The opposite theory to this is [[solipsism]]. Some argue that naïve realism fails to take into account the psychology of [[perception]], but naïve realists argue that viewing the psychology of [[perception]] as a problem for naïve realism requires begging the question in favor of idealism. (''See: [[G.E. Moore]]''.) |

||

| + | ===Responses to skepticism=== |

||

| − | === Phenomenalism === |

||

| + | ====Contextualism==== |

||

| − | [[Phenomenalism]] is a development from [[George Berkeley]]'s claim that to be is to be perceived. According to phenomenalism, when you see a tree, you see a certain perception of a brown shape, when you touch it, you get a perception of pressure against your palm. On this view, one shouldn't think of objects as distinct substances, which interact with our senses so that we may perceive them; rather we should conclude that the perception itself is all that really exists. |

||

| + | {{main|Contextualism}} |

||

| + | Contextualism in epistemology is the claim that knowledge varies with the context in which it is attributed. More precisely, contextualism is the claim that, in a sentence of the form, "''S'' knows that ''P''," the relation between ''S'' and ''P'' depends on the context of discussion. According to the contextualist, the term "knows" is context-sensitive in a way similar to words such as "poor", "tall", and "flat". (Opposed to this contextualism are several forms of what is called "[[invariantism]]", the theory that the meaning of the term "knowledge", and hence the proposition expressed by the sentence, "''S'' knows that ''P''," does not vary from context to context.) The motivation behind contextualism is the idea that, in the context of discussion with an extreme skeptic about knowledge, there is a very high standard for the accurate ascription of knowledge, while in ordinary usage, there is a lower standard. Hence, contextualists attempt to evade skeptical conclusions by maintaining that skeptical arguments against knowledge are not relevant to our ordinary usages of the term. |

||

| − | === |

+ | ====Fallibilism==== |

| + | {{main|Fallibilism}} |

||

| − | [[Pragmatism]] about knowledge holds that what is important about knowledge is that it solves certain problems that are constrained both by the world and by human purposes. The place of knowledge in human activity is to resolve the problems that arise in conflicts between belief and action. Pragmatists are also typically committed to the use of the experimental method in all forms of inquiry, a non-skeptical fallibilism about our current store of knowledge, and the importance of knowledge proving itself through future testing. |

||

| + | For most of philosophical history, "knowledge" was taken to mean belief that was true and justified to an absolute [[certainty]].{{Fact|date=February 2007}} Early in the 20th Century, however, the notion that belief had to be justified as such to count as knowledge lost favour. Fallibilism is the view that knowing something does not entail certainty regarding it. |

||

| + | {{sectstub}} |

||

| − | === Rationalism === |

||

| − | [[continental rationalism|Rationalists]] believe that there are [[a priori]] or [[innate ideas]] that are not derived from [[sense experience]]. These ideas, however, may be justified by experience. These ideas may in some way derive from the structure of the human [[mind]], or they may exist independently of the mind. If they exist independently, they may be understood by a human mind once it reaches a necessary degree of sophistication. |

||

| + | ==Practical applications== |

||

| − | The epitome of the rationalist view is [[Descartes]]' ''[[Cogito ergo sum]]'' ("I think, therefore I am"), in which the skeptic is invited to consider that the mere fact that he doubts this claim implies that there is a doubter. Because doubting is a kind of thinking, the claim must be correct. [[Spinoza]] derived a rationalist system in which there is only one substance, [[God]]. [[Leibniz]] derived a system in which there are an infinite number of substances, his ''[[monad|Monads]]''. |

||

| + | Far from being purely academic, the study of epistemology is useful for a great many applications. It is particularly commonly employed in issues of law where proof of guilt or innocence may be required, or when it must be determined whether a person knew a particular fact before taking a specific action (e.g., whether an action was premeditated). |

||

| + | Other common applications of epistemology include: |

||

| − | === Representationalism === |

||

| + | * Mathematics and science |

||

| − | [[Representationalism]] or [[representative realism]], unlike naïve realism, proposes that we cannot see the external world directly, but only through our perceptual representations of it. In other words, the objects and the world that you see around you are not the world itself, but merely an internal virtual-reality replica of that world. The so-called [[veil of perception]] removes the real world from our direct inspection. |

||

| + | * History and archaeology |

||

| + | * Medicine (diagnosis of disease) |

||

| + | * Product testing (How can we know that the product will not fail?) |

||

| + | * Intelligence gathering |

||

| + | * Religion and Apologetics |

||

| + | * [[Cognitive Science]] |

||

| + | * [[Artificial Intelligence]] |

||

| + | * [[Psychology]] |

||

| + | * [[Linguistics]] |

||

| + | * [[Philosophy]] |

||

| + | * [[Knowledge Management]] |

||

| + | * [[Philosophical problems of testimony | Testimony]] |

||

| + | {{sectstub}} |

||

| + | ==Intercultural References== |

||

| − | ===Relativism=== |

||

| − | [[Relativism]] as advocated by [[Protagoras]] maintains that all things are true and in a constant state of flux, revealing certain aspects of truth at one time while concealing them at another. It claims that there is no objective truth: anything which a person can perceive is true for that person, but not necessarily true for the next person. By equating perceptions and beliefs with truth, overt self-contradiction is avoided. |

||

| + | In [[Indian philosophy]], the [[Sanskrit]] term for the equivalent branch of study is "[[pramana]]."<ref name=Kuijp>{{cite book|author=Kuijp, Leonard W. J. van der (ed.)|title=Contributions to the development of Tibetan Buddhist epistemology: from the eleventh to the thirteenth century|year=1983|publisher=F. Steiner}}</ref><ref>[http://www.jstor.org/view/0041977x/ap020109/02a00490/0]</ref> |

||

| − | === Skepticism === |

||

| − | [[Skepticism|Philosophical skepticism]] holds that one can never have sufficient justification in a belief to have knowledge. By contrast, [[scientific skepticism]] is the practical stance that one should accept claims only given solid evidence. |

||

| − | == |

+ | ==See also== |

| + | {{col-begin}} |

||

| − | * [[Contextualism]] |

||

| + | {{col-break}} |

||

| − | * [[Eastern epistemology]] |

||

| + | *[[Adaptive representation]] |

||

| − | * [[Ethics]] |

||

| − | * |

+ | *[[Analytic tradition]] |

| + | *[[Bayesian probability]] |

||

| − | * [[Methodology]] |

||

| + | *[[Constructivist epistemology]] |

||

| − | * [[Methods of obtaining knowledge]] |

||

| + | *[[Determinism]] |

||

| − | * [[Philosophy of perception|Perception]] |

||

| + | *[[Eastern epistemology]] |

||

| − | * [[Philosophy of science]] |

||

| + | *[[Genetic epistemology]] |

||

| − | * [[Reason]] |

||

| − | * |

+ | *[[Evidentialism]] |

| + | *[[Evidentiality]] |

||

| − | * [[Scientific modeling]] |

||

| + | {{col-break}} |

||

| − | * [[Self-evidence]] |

||

| + | *[[Hermeneutics]] |

||

| − | * [[Social epistemology]] |

||

| + | *[[Metaphysics]] |

||

| − | * [[Subjective idealism]] |

||

| + | *[[Methodology]] |

||

| − | * [[Transcendental idealism]] |

||

| + | *[[Methods of obtaining knowledge]] |

||

| − | * [[Virtue epistemology]] |

||

| + | *[[Objectivist epistemology]] |

||

| − | * [[Analytic tradition]] |

||

| − | * |

+ | *[[Platonic epistemology]] |

| + | {{col-break}} |

||

| − | * [[Evidentiality]] (linguistics) |

||

| + | *[[Positivism (philosophy)]] |

||

| + | *[[Reason]] |

||

| + | *[[Relativism]] |

||

| + | *[[Self-evidence]] |

||

| + | *[[Social epistemology]] |

||

| + | *[[Virtue epistemology]] |

||

| + | {{col-end}} |

||

| + | ==Notes== |

||

| − | == External links and references == |

||

| + | <div class="references-small"> |

||

| − | * [http://pantheon.yale.edu/~kd47/e-page.htm The Epistemology Page] by Keith DeRose |

||

| + | <references /> |

||

| − | * [http://home.sprynet.com/~owl1/epistemo.htm Epistemology Papers] by Michael Huemer |

||

| + | </div> |

||

| − | * [http://www.galilean-library.org/int5.html Epistemology Introduction, Part 1] and *[http://www.galilean-library.org/int20.html Part 2] by Paul Newall at the Galilean Library. |

||

| + | |||

| − | * [http://www.ditext.com/clay/know.html Marjorie Clay (ed.), ''Teaching Theory of Knowledge'', The Council for Philosophical Studies, 1986.] |

||

| + | ==References and further reading== |

||

| − | * Boufoy-Bastick, Z. (2005). [http://zach.securitymeltdown.com/papers/Attainable-Knowledge-Boufoy-Bastick,Z.pdf Introducing 'Applicable Knowledge' as a Challenge to the Attainment of Absolute Knowledge]. ''Sophia Journal of Philosophy'', 8, 39-51. |

||

| + | |||

| − | * [http://www.ditext.com/gettier/gettier.html Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?] from ''Analysis'', Vol. 23, pp. 121-23 (1963) by [[Edmund L. Gettier]], transcribed by Andrew Chrucky (Sept. 13, 1997). |

||

| + | * The [http://www.ucl.ac.uk/philosophy/LPSG/ London Philosophy Study Guide] offers many suggestions on what to read, depending on the student's familiarity with the subject: [http://www.ucl.ac.uk/philosophy/LPSG/Ep&Meth.htm Epistemology & Methodology] |

||

| − | * Richard Kirkham, "Does the Gettier Problem Rest on a Mistake?" Mind, 93, 1984. |

||

| + | <div class="references-small" style="-moz-column-count: 2; column-count: 2;"> |

||

| − | * Bertrand Russell, [http://www.ditext.com/russell/russell.html ''The Problems of Philosophy'' (1912)] |

||

| + | * Annis, David. 1978. "A Contextualist Theory of Epistemic Justification", in ''American Philosophical Quarterly'', 15: 213-219. |

||

| − | * Ayn Rand, [http://www.noblesoul.com/orc/books/rand/itoe.html ''Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology'' (1979)] |

||

| + | * Boufoy-Bastick, Z. 2005. "Introducing 'Applicable Knowledge' as a Challenge to the Attainment of Absolute Knowledge", ''Sophia Journal of Philosophy'', 8: 39-51. |

||

| − | * [http://www.groovyweb.uklinux.net/?page_name=philosophy%20of%20knowledge&category=philosophy Groovyweb] |

||

| + | * Bovens, Luc & Hartmann, Stephan. 2003. ''Bayesian Epistemology''. Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

||

| − | * [http://www.philosophyonline.co.uk/tok/tokhome.htm Philosophy online] |

||

| + | * Butchvarov, Panayot. 1970. ''The Concept of Knowledge''. Evanston, Northwestern University Press. |

||

| + | * Cohen, Stewart. 1998. "Contextualist Solutions to Epistemological Problems: Scepticism, Gettier, and the Lottery." ''Australasian Journal of Philosophy'', 76: 289-306. |

||

| + | * Cohen Stewart. 1999. "Contextualism, Skepticism, and Reasons", in Tomberlin 1999. |

||

| + | * DeRose, Keith. 1992. "Contextualism and Knowledge Attributions", ''Philosophy and Phenomenological Research'', 15: 213-19. |

||

| + | * DeRose, Keith. 1999. "Contextualism: An Explanation and Defense", in Greco and Sosa 1999. |

||

| + | * Feldman, Richard. 1999. "Contextualism and Skepticism", in Tomberlin 1999, pp. 91-114. |

||

| + | * Gettier, Edmund. 1963. "Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?", ''Analysis'', Vol. 23, pp. 121-23. [http://www.ditext.com/gettier/gettier.html Online text]. |

||

| + | * Greco, J. & Sosa, E. 1999. ''Blackwell Guide to Epistemology'', Blackwell Publishing. |

||

| + | * Hawthorne, John. 2005. "The Case for Closure", ''Contemporary Debates in Epistemology'', Peter Sosa and Matthias Steup (ed.): 26-43. |

||

| + | * Hendricks, Vincent F. 2006. ''Mainstream and Formal Epistemology'', New York: Cambridge University Press. |

||

| + | * Kant, Immanuel. 1781. ''[[Critique of Pure Reason]]'' |

||

| + | * Keeton, Morris T. 1962. "Empiricism", in ''Dictionary of Philosophy'', Dagobert D. Runes (ed.), Littlefield, Adams, and Company, Totowa, NJ, pp. 89–90. |

||

| + | * Kirkham, Richard. 1984. "Does the Gettier Problem Rest on a Mistake?" ''Mind'', 93. |

||

| + | * Klein, Peter. 1981. ''Certainty: a Refutation of Scepticism'', Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. |

||

| + | * Kyburg, H.E. 1961. ''Probability and the Logic of Rational Belief'', Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press. |

||

| + | * Lewis, David. 1996. "Elusive Knowledge." ''Australian Journal of Philosophy'', 74, 549-67. |

||

| + | * Machado, A., Lourenco, O., & Silva, F. J. (2000). [http://www.behavior.org/journals_bp/2000/machado.pdf Facts, concepts, and theories: The shape of psychology's epistemic triangle.] ''[[Behavior and Philosophy]], 28,'' 1-40. |

||

| + | * Morin, Edgar. 1986. ''La Méthode, Tome 3, La Connaissance de la connaissance'' (Method, 3rd volume : The knowledge of knowledge) |

||

| + | * Preyer, G./Siebelt, F./Ulfig, A. 1994. ''Language, Mind and Epistemology'', Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. |

||

| + | * Rand, Ayn. 1979. ''Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology'', New York: Meridian. |

||

| + | * Russell, Bertrand. 1912. ''The Problems of Philosophy'', New York: Oxford University Press. |

||

| + | * Schiffer, Stephen. 1996. "Contextualist Solutions to Scepticism", ''Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society'', 96:317-33. |

||

| + | * Steup, Matthias. 2005. "Knowledge and Scepticism", ''Contemporary Debates in Epistemology'', Peter Sosa and Matthias Steup (eds.): 1-13. |

||

| + | * Tomberlin, James (ed.). 1999. ''Philosophical Perspectives 13, Epistemology'', Blackwell Publishing. |

||

| + | * Wittgenstein, Ludwig. 1922. ''[[Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus]]'', C.K. Ogden (trns.), Dover. [http://www.kfs.org/~jonathan/witt/tlph.html Online text]. |

||

| + | </div> |

||

| + | |||

| + | ==External links and references== |

||

| + | '''''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' articles:''' |

||

| + | * [http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/epistemology-bayesian/ Bayesian Epistemology] by William Talbott. |

||

| + | * [http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/epistemology/ Epistemology] by Matthias Steup. |

||

| + | * [http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/epistemology-evolutionary/ Evolutionary Epistemology] by Michael Bradie & William Harms. |

||

| + | * [http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/feminism-epistemology/ Feminist Epistemology and Philosophy of Science] by Elizabeth Anderson. |

||

| + | * [http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/epistemology-naturalized/ Naturalized Epistemology] |

||

| + | by Richard Feldman. |

||

| + | * [http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/epistemology-social/ Social Epistemology] by Alvin Goldman. |

||

| + | * [http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/epistemology-virtue/ Virtue Epistemology] by John Greco. |

||

| + | |||

| + | '''Other links:''' |

||

| + | * [http://pantheon.yale.edu/~kd47/What-Is-Epistemology.htm What Is Epistemology?] — a brief introduction to the topic by Keith DeRose. |

||

| + | * [http://www.missouri.edu/%7ekvanvigj/certain_doubts/ Certain Doubts] — a group blog run by Jonathan Kvanvig, with many leading epistemologists as contributors. |

||

| + | * [http://www.db.dk/jni/lifeboat/home.htm The Epistemological Lifeboat] by Birger Hjørland & Jeppe Nicolaisen (eds.) |

||

| + | * [http://pantheon.yale.edu/~kd47/e-page.htm The Epistemology Page] by Keith DeRose. |

||

| + | *[http://journal.ilovephilosophy.com/Article/Justified-True-Belief-and-Critical-Rationalism/220 Justified True Belief and Critical Rationalism] by Mathew Toll |

||

| + | * [http://home.sprynet.com/~owl1/epistemo.htm Epistemology Papers] a collection of Michael Huemer's. |

||

| + | * [http://www.galilean-library.org/int5.html Epistemology Introduction, Part 1] and [http://www.galilean-library.org/int20.html Part 2] by Paul Newall at the Galilean Library. |

||

| + | * [http://www.ditext.com/clay/know.html ''Teaching Theory of Knowledge'' (1986)] — Marjorie Clay (ed.), an electronic publication from The Council for Philosophical Studies. |

||

| + | * [http://www.groovyweb.uklinux.net/?page_name=philosophy%20of%20knowledge&category=philosophy Epistemology: The Philosophy of Knowledge] — an introduction at Groovyweb. |

||

| + | * [http://www.philosophyonline.co.uk/tok/tokhome.htm Introduction to Theory of Knowledge] — from PhilosophyOnline. |

||

| + | * [http://www.theoryofknowledge.info/ Theory of Knowledge] — an introduction to epistemology, exploring the various theories of knowledge, justification, and belief. |

||

| + | * [http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=904833 A Theory of Knowledge] by Clóvis Juarez Kemmerich, on the Social Science Research Network, 2006. |

||

* [http://www.galilean-library.org/int5.html An Introduction to Epistemology] by Paul Newall, aimed at beginners. |

* [http://www.galilean-library.org/int5.html An Introduction to Epistemology] by Paul Newall, aimed at beginners. |

||

| + | * [http://davidspeakslive.com David Speaks Live — A lecture on Ontological Epistemology] |

||

| − | * [http://www.philosophyofreligion.info/reformedepistemology.html Reformed Epistemology] by Tim Holt |

||

| + | * [http://observacionesfilosoficas.net/epistemologia.htm Epistemology in Revista Observaciones Filosoficas] |

||

| − | * Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: |

||

| − | * |

+ | *[http://www.legionofmarytidewater.com/faith/Epistemology.htm Catholic Epistomology] |

| − | ** [http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/epistemology-bayesian/ Bayesian Epistemology] |

||

| − | ** [http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/epistemology-evolutionary/ Evolutionary Epistemology] |

||

| − | ** [http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/feminism-epistemology/ Feminist Epistemology and Philosophy of Science] |

||

| − | ** [http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/epistemology-naturalized/ Naturalized Epistemology] |

||

| − | ** [http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/epistemology-social/ Social Epistemology] |

||

| − | ** [http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/epistemology-virtue/ Virtue Epistemology] |

||

| − | ** [http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/sense-data/ Sense Data] |

||

| − | * [http://www.solagratia.org/Search.aspx?q=epistemology Articles on Christian Epistemology] |

||

| − | * [http://www.missouri.edu/%7ekvanvigj/certain_doubts/ Certain Doubts] (interactive epistemic discussion) |

||

{{Philosophy navigation}} |

{{Philosophy navigation}} |

||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <!-- |

||

| + | [[af:Epistemologie]] |

||

| + | [[zh-min-nan:Jīn-sek-lūn]] |

||

| + | [[bg:Епистемология]] |

||

| + | [[ca:Epistemologia]] |

||

| + | [[cs:Gnozeologie]] |

||

| + | [[da:Erkendelsesteori]] |

||

| + | [[de:Épistémologie]] |

||

| + | [[et:Epistemoloogia]] |

||

| + | [[es:Epistemología]] |

||

| + | [[fa:شناختشناسی]] |

||

| + | [[fr:Épistémologie]] |

||

| + | [[gl:Epistemoloxía]] |

||

| + | [[hr:Gnoseologija]] |

||

| + | [[io:Epistemologio]] |

||

| + | [[id:Epistemologi]] |

||

| + | [[it:Epistemologia]] |

||

| + | [[he:תורת ההכרה]] |

||

| + | [[la:Epistemologia]] |

||

| + | [[hu:Ismeretelmélet]] |

||

| + | [[nl:Wetenschapsfilosofie]] |

||

| + | [[ja:認識論]] |

||

| + | [[no:Erkjennelsesteori]] |

||

| + | [[pl:Epistemologia]] |

||

| + | [[pt:Epistemologia]] |

||

| + | [[ru:Эпистемология]] |

||

| + | [[sq:Epistimologjia]] |

||

| + | [[sk:Epistemológia]] |

||

| + | [[sl:Gnoseologija]] |

||

| + | [[sr:Гносеологија]] |

||

| + | [[fi:Tietoteoria]] |

||

| + | [[tl:Epistemolohiya]] |

||

| + | [[th:ญาณวิทยา]] |

||

| + | [[uk:Епістемологія]] |

||

| + | [[zh-yue:知識論]] |

||

| + | [[zh:科学哲学]] |

||

| + | --> |

||

| + | {{enWP|Epistemology}} |

||

[[Category:Branches of philosophy]] |

[[Category:Branches of philosophy]] |

||

[[Category:Epistemology| ]] |

[[Category:Epistemology| ]] |

||

Revision as of 10:22, 15 May 2013

Assessment |

Biopsychology |

Comparative |

Cognitive |

Developmental |

Language |

Individual differences |

Personality |

Philosophy |

Social |

Methods |

Statistics |

Clinical |

Educational |

Industrial |

Professional items |

World psychology |

Philosophy Index: Aesthetics · Epistemology · Ethics · Logic · Metaphysics · Consciousness · Philosophy of Language · Philosophy of Mind · Philosophy of Science · Social and Political philosophy · Philosophies · Philosophers · List of lists

According to Plato, knowledge is a subset of that which is both true and believed

Epistemology or theory of knowledge is the branch of philosophy that studies the nature and scope of knowledge and belief. The term "epistemology" is based on the Greek words "ἐπιστήμη or episteme" (knowledge or science) and "λόγος or logos" (account/explanation); it was introduced into English by the Scottish philosopher James Frederick Ferrier (1808-1864).[1]

Epsistemological theories in philosophy are a ways of analyzing the nature of knowledge and how it relates notions such as truth, belief, and justification. It also deals with the means of production of knowledge, as well as skepticism about different knowledge claims. In other words, epistemology primarily addresses the following questions: "What is knowledge?", "How is knowledge acquired?", and "What do people know?".

Psychologists have greatly contributed to elucidating the answer to the latter two questions making them the subject of empirical investigation rather than philosophical speculation.

There are many different topics, stances, and arguments in the field of epistemology. Recent psychological studies have dramatically challenged centuries-old assumptions, and the discipline therefore continues to be vibrant and dynamic.

Defining knowledge

The first issue epistemology must address is the question of what knowledge is. This question is several millennia old, and among the most prominent in epistemology.

Distinguishing knowing that from knowing how

In this article, and in epistemology in general, the kind of knowledge usually discussed is propositional knowledge, also known as "knowledge-that" as opposed to "knowledge-how". For example: in mathematics, it is knowing that 2 + 2 = 4, but there is also knowing how to add two numbers. Or, one knows how to ride a bicycle and one knows that a bicycle has two wheels.

Philosophers thus distinguish between theoretical reason (knowing that) and practical reason (knowing how), with epistemology being interested primarily in theoretical knowledge. This distinction is recognised linguistically in many languages but not in English. In French (as well as in Portuguese and Spanish), for example, to know a person is 'connaître' ('conhecer' / 'conocer'), whereas to know how to do something is 'savoir' ('saber' in both Portuguese and Spanish). In Italian the verbs are respectively 'conoscere' and 'sapere' and the nouns for 'knowledge' are 'conoscenza' and 'sapienza'. In the German language, it is exemplified with the verbs "kennen" and "wissen." "Wissen" implies knowing as a fact, "kennen" implies knowing in the sense of being acqainted with and having a working knowledge of. But neither of those verbs do truly extend to the full meaning of the subject of epistemology. In German, there is also a verb derived from "kennen", namely "erkennen", which roughly implies knowledge in form of recognition or acknowledgment, strictly metaphorically. The verb itself implies a process: you have to go from one state to another: from a state of "not-erkennen" to a state of true erkennen. This verb seems to be the most appropriate in terms of describing the "episteme" in one of the modern European languages.

Belief

- Main article: Belief

Sometimes, when people say that they believe in something, what they mean is that they predict that it will prove to be useful or successful in some sense — perhaps someone might "believe in" his or her favorite football team. This is not the kind of belief usually addressed within epistemology. The kind that is dealt with, as such, is where "to believe something" just means to think that it is true — e.g., to believe that the sky is blue is to think that the proposition, "The sky is blue," is true.

Knowledge implies belief. Consider the statement, "I know P, but I don't believe that P is true." This statement is contradictory. To know P is, among other things, to believe that P is true, i.e. to believe in P. (See the article on Moore's paradox.)

Truth

- Main article: Truth

If someone believes something, he or she thinks that it is true, but he or she may be mistaken. This is not the case with knowledge. For example, suppose that Jeff thinks that a particular bridge is safe, and attempts to cross it; unfortunately, the bridge collapses under his weight. We might say that Jeff believed that the bridge was safe, but that his belief was mistaken. We would not accurately say that he knew that the bridge was safe, because plainly it was not. For something to count as knowledge, it must actually be true.

Justified true belief

- Main article: Theaetetus (dialogue)