No edit summary |

|||

| (11 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{Clinpsy}} |

||

| + | -------- |

||

| + | |||

{{Boxtop}} |

{{Boxtop}} |

||

{{DiseaseDisorder infobox | |

{{DiseaseDisorder infobox | |

||

| Line 15: | Line 18: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

{{Boxbottom}} |

{{Boxbottom}} |

||

| − | '''Down syndrome''' (US, Canada and other countries) or '''Down's syndrome''' (UK and other countries) encompasses a number of chromosomal abnormalities, of which [[Aneuploidy#Trisomy|trisomy]] [[Chromosome 21|21]] (an [[aneuploidy|aneuploid]]) is the most common, causing highly variable degrees of [[learning difficulties]] as well as [[disability|physical disabilities]]. It is named for [[John Langdon Down]], the British doctor who first described it in [[1866]]. |

||

| + | '''Down syndrome''' ('''Down's Syndrome''' in British English<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ds-health.com/trisomy.htm |title=Trisomy 21: The Story of Down Syndrome paper}}</ref>) is a [[genetic disorder]] caused by the presence of all or part of an extra [[chromosome 21 (human)|21st chromosome]]. It is named after [[John Langdon Down]], the British doctor who first described it in 1866. The condition is characterized by a combination of major and minor differences in body structure. Often Down syndrome is associated with some impairment of [[cognition|cognitive]] ability and [[child development|physical growth]] as well as facial appearance. Down syndrome is usually identified at birth. |

||

| − | == Overview == |

||

| − | The incidence of Down syndrome is estimated at 1 per 800 births, making it the most common human [[aneuploidy]]. [[Maternal age effect|Maternal age]] influences the chance of conceiving a baby with the syndrome. At age 20 to 24, it is 1/1490, while at age 40 it is 1/106, and at age 49 is 1/11. (Hook EB., 1981). Although the chance increases with maternal age, most children with Down syndrome (80%) are born to women under the age of 35. This reflects the overall fertility of that age group. Many standard screens of pregnancies indicate Down syndrome, although they are not very accurate. [[Genetic counseling]] along with [[genetic testing]], such as [[amniocentesis]] or [[chorionic villus sampling]], are usually offered to families who may have an increased chance of having a child with Down syndrome. |

||

| + | Individuals with Down syndrome can have a lower than average cognitive ability, often ranging from mild to moderate [[mental retardation]]. Developmental disabilities often manifest as a tendency toward concrete thinking or [[naïveté]]. A small number have severe to profound mental retardation. The [[incidence (epidemiology)|incidence]] of Down syndrome is estimated at 1 per 800 to 1 per 1,000 births. |

||

| − | While most children with Down syndrome have a lower than average cognitive function, some have earned college degrees with accommodations, and nearly all will learn to read, write and do simple mathematics. The common clinical features of Down syndrome include any of a number of features that also appear in people with a standard set of chromosomes. They include a [[simian crease]] (a single crease across one or both palms), almond shaped eyes, shorter limbs, heart and/or gastroesophageal defects, speech impairment, and perhaps a higher than average risk of incidence of [[Hirschsprung's disease]]. Young children with Down syndrome are also more prone to recurrent [[ear infections]] and [[obstructive sleep apnea]]. |

||

| + | Many of the common physical features of Down syndrome also appear in people with a standard set of chromosomes. They include a single transverse palmar crease (a single instead of a double crease across one or both palms), an almond shape to the eyes caused by an epicanthic fold of the eyelid, shorter limbs, poor muscle tone, and protruding tongue. Health concerns for individuals with Down syndrome include a higher risk for congenital heart defects, gastroesophageal reflux disease, recurrent ear infections, [[obstructive sleep apnea]], and [[thyroid]] dysfunctions. |

||

| − | Early educational intervention, screening for common problems, such as [[thyroid]] functioning, medical treatment where indicated, a conducive family environment, vocational training, ''etc''., can improve the overall development of children with Down syndrome. On the one hand, Down syndrome shows that some genetic limitations cannot be overcome; on the other, it shows that education can produce excellent progress whatever the starting point. The commitment of parents, teachers, and therapists to individual children has produced previously unexpected positive results. |

||

| + | [[Early Childhood Intervention|Early childhood intervention]], screening for common problems, medical treatment where indicated, a conducive family environment, and [[vocational training]] can improve the overall development of children with Down syndrome. Although some of the physical genetic limitations of Down syndrome cannot be overcome, education and proper care will improve quality of life.<ref>Roizen NJ, Patterson D.''Down's syndrome.'' Lancet. 2003 [[12 April]];361(9365):1281-9. Review. PMID 12699967</ref> |

||

| − | == History == |

||

| − | [[John Langdon Down]] first characterized Down syndrome in 1862 (widely published in 1866). Because of his perception that Down syndrome children share physical similarities ([[Epicanthal fold|epicanthal folds]]) with Mongolians, he used the terms '''mongolism''' or '''mongolian idiocy'''. At the time, the vast majority of people with Down syndrome were [[institutionalization|institutionalized]]. The reference to racial characeristics was typical of the day and the growing [[eugenics]] movement. Into the 20<sup>th</sup> Century, individuals with Down syndrome (and other disabilities) were [[institutionalization|institutionalized]] and often forcibly sterilized (33 of the, then, 48 United States had forced sterilization laws). The [[Germany|German]] program [[T-4 Euthanasia Program|"Aktion T-4"]] ([[1940]]) was a [[euthanasia]] program aimed at various disabilities, including Down syndrome. These programs have since been discredited and forced institutionalization is atypical in Western countries. |

||

| + | ==Characteristics== |

||

| − | In 1959, [[Jerome Lejeune|Professor Jérome Lejeune]] discovered that Down syndrome is a chromosomal irregularity [http://www.fondationlejeune.org/eng/Content/Fondation/professeurlj.asp]. The chromosomal irregularity was identified as '''[[Aneuploidy#Trisomy|trisomy]] [[Chromosome 21|21]]'''. The human [[karyotype]] is numbered from largest to smallest (excluding the X and Y), and Lejeune ascribed the trisomy to chromosome 21, the second smallest. This is incorrect. The chromosome that causes Down syndrome should have been designated 22, the smallest. By the time the mistake was discovered, it was too late to change the karyotype order. |

||

| + | [[Image:Brushfield.jpg|thumb|right|Example of white spots on the [[iris (anatomy)|iris]] known as ''Brushfield spots'']] |

||

| + | Individuals with Down syndrome may have some or all of the following physical characteristics: oblique eye fissures with epicanthic skin folds on the inner corner of the eyes, [[muscle hypotonia]] (poor muscle tone), a flat nasal bridge, a single palmar fold (also known as a simian crease), a protruding tongue (due to small oral cavity, and an enlarged tongue near the tonsils), a short neck, white spots on the [[Eye#Anatomy of the mammalian eye|iris]] known as Brushfield spots,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.medterms.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=6570 |title=Definition of Brushfield's Spots}}</ref> excessive flexibility in joints, congenital heart defects, excessive space between large toe and second toe, a single flexion furrow of the fifth finger, and a higher number of ulnar loop [[Dermatoglyphics|dermatoglyphs]]. Most individuals with Down syndrome have [[mental retardation]] in the mild (IQ 50–70) to moderate (IQ 35–50) range,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.keepkidshealthy.com/welcome/conditions/downsyndrome.html |title=Keep Kids Healthy article on Down syndrome |accessedate=2006-04-10}}</ref> with scores of children having Mosaic Down syndrome (explained below) typically 10–30 points higher.<ref>{{cite web |author=Strom, C |url=http://www.mosaicdownsyndrome.com/faqs.htm |title=FAQ from Mosaic Down Syndrome Society |accessdate = 2006-06-03}}</ref> In addition, individuals with Down syndrome can have serious abnormalities affecting any body system. |

||

| + | ==Genetics== |

||

| − | In 1961 a group of geneticists wrote to the editor of ''[[The Lancet]]'' suggesting that the name be changed. They gave him several choices, and he chose ''Down's Syndrome''. The [[World Health Organization]] (WHO) confirmed this designation in 1965 [http://www.intellectualdisability.info/values/history_DS.htm 2]. In 1974, the United States National Institute of Health called a conference to standardize the naming of diseases and disorders. They recommended eliminating the possessive form ("The possessive form of an eponym should be discontinued, since the author neither had nor owned the disorder."). ''Down syndrome'' is the accepted term in the USA, Canada and other countries, and the possessive form is used in the United Kingdom and other countries. |

||

| + | {{main|Genetic origins of Down syndrome}} |

||

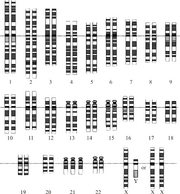

| + | [[Image:Down_Syndrome_Karyotype.png|right|thumb|[[Karyotype]] for trisomy Down syndrome. Notice the three copies of chromosome 21]] |

||

| + | Down syndrome is a chromosomal abnormality characterized by the presence of an extra copy of genetic material on the [[Chromosome 21 (human)|21st chromosome]], either in whole ([[Aneuploidy#Trisomy|trisomy]] 21) or part (such as due to [[Chromosomal translocation|translocations]]). The effects of the extra copy vary greatly among individuals, depending on the extent of the extra copy, genetic background, environmental factors, and random chance. Down syndrome occurs in all human populations, and analogous effects have been found in other species such as chimpanzees<ref>McClure HM, Belden KH, Pieper WA, Jacobson CB. Autosomal trisomy in a chimpanzee: resemblance to Down's syndrome. ''Science.'' 1969 [[5 September]];165(897):1010-2. PMID 4240970</ref> and mice. Recently, researchers have created [[transgenic]] mice with most of human chromosome 21 (in addition to the normal mouse chromosomes).<ref>{{cite web |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/4268226.stm |title=Down's syndrome recreated in mice| publisher=BBC News |accessdate = 2006-06-14 |date=2005-09-22}}</ref> The extra chromosomal material can come about in several distinct ways. A normal human karyotype is designated as 46,XX or 46,XY, indicating 46 chromosomes with an XX arrangement for females and 46 chromosomes with an XY arrangement for males.<ref>For a description of human karyotype see {{cite web |author=Mittleman, A. (editor) |year=1995 |url=http://www.iscn1995.org/ |title=An International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomeclature |accessdate = 2006-06-04}}</ref> |

||

| + | ===Trisomy 21=== |

||

| − | == Genetic Causes == |

||

| + | Trisomy 21 (47,XX,+21) is caused by a [[Meiosis|meiotic]] [[nondisjunction]] event. With nondisjunction, a [[gamete]] (''i.e.'', a sperm or egg cell) is produced with an extra copy of chromosome 21; the gamete thus has 24 chromosomes. When combined with a normal gamete from the other parent, the [[embryo]] now has 47 chromosomes, with three copies of chromosome 21. Trisomy 21 is the cause of approximately 95% of observed Down syndromes, with 88% coming from nondisjunction in the maternal gamete and 8% coming from nondisjunction in the paternal gamete.<ref name="occurrence">{{cite web |url=http://www.nichd.nih.gov/publications/pubs/downsyndrome.cfm#TheOccurrence |title=Down syndrome occurrence rates (NIH) |accessdate = 2006-06-02}}</ref> |

||

| − | Down syndrome is a chromosomal abnormality characterized by the presence of an extra copy of genetic material on the [[Chromosome 21|21]]st chromosome, either in whole ([[Aneuploidy#Trisomy|trisomy]] [[Chromosome 21|21]]) or part (such as due to [[Chromosomal translocation|translocations]]). The effects of the extra copy varies greatly from individual to individual, depending on the extent of the extra copy, genetic background, environmental factors, and random chance. Down syndrome can occur in all human populations, and analogous effects have been found in other species, such as chimpanzees and mice. |

||

| + | ===Mosaicism=== |

||

| − | Down syndrome has four root causes: |

||

| + | [[Trisomy 21]] is caused prior to conception, and all cells in the body are affected. However, when some of the cells in the body are normal and other cells have trisomy 21, it is called [[Mosaic (genetics)|Mosaic]] Down syndrome (46,XX/47,XX,+21).<ref>[http://www.mosaicdownsyndrome.com Mosaic Down syndrome on the Web]</ref> This can occur in one of two ways: A [[nondisjunction]] event during an early cell division in a normal embryo leads to a fraction of the cells with trisomy 21; or a Down syndrome embryo undergoes nondisjunction and some of the cells in the embryo revert back to the normal chromosomal arrangement. There is considerable variability in the fraction of trisomy 21, both as a whole and among tissues. This is the cause of 1–2% of the observed Down syndromes.<ref name="occurrence" /> |

||

| − | * Trisomy 21 is caused by a meiotic nondisjunction event. In this case the child has three copies of every gene on [[Chromosome 21|chromosome 21]]. This is the cause of 95% of observed Down syndromes. |

||

| − | * The extra material is due to a [[Robertsonian translocation]]. The long arm of [[Chromosome 21|21]] is attached to another chromosome (often [[Chromosome 14|chromosome 14]] or itself). The parent with the translocation is missing information on the short arm of 21, but this does not have apparent effects. Through normal disjunction during meiosis, gametes are produced with extra copies of the long arm of [[Chromosome 21|chromosome 21]]. There is variability in the extra region. This is the cause of 2-3% of the observed Down syndromes, and is often referred to as 'familial Down syndrome'. |

||

| − | * The individual is a mosaic of normal chromosomal arrangements and trisomy 21. This can occur in one of two ways: A [[nondisjunction]] event during an early cell division leads to a fraction of the cells with [[Aneuploidy#Trisomy|trisomy]] [[Chromosome 21|21]]; or A Down syndrome embryo undergoes [[nondisjunction]] and some of the cells in the embryo revert back to the normal chromosomal arrangement. There is considerable variability in the fraction of [[Aneuploidy#Trisomy|trisomy]] [[Chromosome 21|21]], both as a whole and tissue-by-tissue. This is the cause of 1-2% of the observed Down syndromes. Is it likely that all people have an extremely small fraction of their cells that are [[Aneuploidy#Trisomy|trisomy]] [[Chromosome 21|21]]. |

||

| − | * Rarely, a region of the [[Chromosome 21|21]]<sup>st</sup> chromosome will undergo a duplication event. This will lead to extra copies of some, but not all, of the genes on [[Chromosome 21|chromosome 21]]. |

||

| + | ===Robertsonian translocation=== |

||

| − | Most Down syndrome cases occur spontaneously. There is no known prevention, although some factors, such as increased maternal age, can increase the chance of occurrence. The genetic basis itself cannot be treated, and the variety of expression requires targeting treatment to each individual. |

||

| + | The extra chromosome 21 material that causes Down syndrome may be due to a [[Robertsonian translocation]]. In this case, the long arm of chromosome 21 is attached to another chromosome, often [[Chromosome 14 (human)|chromosome 14]] (45,XX, t(14;21q)) or itself (called an [[isochromosome]], 45,XX, t(21q;21q)). Normal [[disjunction]]s leading to gametes have a significant chance of creating a gamete with an extra chromosome 21. Translocation Down syndrome is often referred to as ''familial Down syndrome''. It is the cause of 2-3% of observed cases of Down syndrome.<ref name="occurrence" /> It does not show the maternal age effect, and is just as likely to have come from fathers as mothers. |

||

| + | ===Duplication of a portion of chromosome 21=== |

||

| − | == Prenatal screening == |

||

| + | Rarely, a region of chromosome 21 will undergo a duplication event. This will lead to extra copies of some, but not all, of the genes on chromosome 21 (46,XX, dup(21q)).<ref>Petersen MB, Tranebjaerg L, McCormick MK, Michelsen N, Mikkelsen M, Antonarakis SE. ''Clinical, cytogenetic, and molecular genetic characterization of two unrelated patients with different duplications of 21q.'' Am J Med Genet Suppl. 1990;7:104-9. |

||

| − | Pregnant women can be screened for various complications in their pregnancy. Some screens are designed to indicate [[neural tube defect]]s (such as [[spina bifida]]), [[Edward's syndrome|Trisomy 18]], or Down syndrome, and other possible problems. There are two common non-invasive screens that can indicate an increased chance for a Down syndrome fetus. |

||

| + | PMID 2149934</ref> If the duplicated region has genes that are responsible for Down syndrome physical and mental characteristics, such individuals will show those characteristics. This cause is very rare and no rate estimates are available. |

||

| − | * Triple Screen. This test measures the maternal serum [[alpha-fetoprotein|alpha feto protein]] (a fetal liver protein), [[estriol]] (a pregnancy hormone), and [[human chorionic gonadotropin]] (hCG, a pregnancy hormone). This screen is done at the 15<sup>th</sup> - 20<sup>th</sup> week. It can detect about 60% of Down syndrome pregnancies. However, it has a 6.5% Initial Positive Rate (IPR) for Down syndrome. Compare this to the 0.1% chance for Down syndrome birth. As with most screens, the chance of a [[False positive|false positive]] is great. The majority of women with a positive result will not have a Down syndrome birth. |

||

| − | * AFP/Free Beta Screen. This test measures the [[alpha-fetoprotein|alpha feto protein]], produced by the fetus, and free beta hCG, produced by the [[placenta]]. It can be done somewhat earlier than the triple screen (13<sup>th</sup> to 22<sup>nd</sup> week). It has an IPR of 2.8% and a detection rate of about 80%. It is not as common as the triple screen. |

||

| − | Even with the best non-invasive screens, the detection rate is only 80% and the rate of false positive is nearly 3%. [[False positive]]s can be caused by undetected multiple fetuses, incorrect date of pregnancy, or normal variation in the proteins. |

||

| + | ==Incidence== |

||

| − | Confirmation of the test is normally accomplished with [[amniocentesis]]. This is an invasive procedure and involves taking [[amniotic fluid]] from the mother and identifying fetal cells. The risk of [[spontaneous abortion]] is approximately 1 in 200 to 1 in 300. The lab work can take a couple of weeks. It will detect over 99.8% of all numerical chromosomal problems, and has a very low false positive rate. |

||

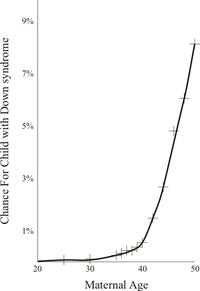

| + | [[Image:Maternal Age Effect.png|thumb|200px|Graph showing increased chance of Down syndrome compared to maternal age.<ref name=Hook>{{cite journal|author = Hook, E.B.|year = 1981|title = Rates of chromosomal abnormalities at different maternal ages|journal = Obstet Gynecol|volume = 58|pages = 282}} PMID 6455611</ref>]] |

||

| + | The incidence of Down syndrome is estimated at 1 per 800 to 1 per 1000 births.<ref name=NIHestimates>Based on estimates by National Institute of Child Health & Human Development {{cite web| title = Down syndrome rates| url=http://www.nichd.nih.gov/publications/pubs/downsyndrome/down.htm| accessdate = 2006-06-21}} |

||

| + | </ref> In 2006, the Center for Disease Control estimated the rate as 1 per 733 live births in the United States (5429 new cases per year).<ref>{{cite journal |author=Center for Disease Control |title=Improved National Prevalence Estimates for 18 Selected Major Birth Defects, United States, 1999-2001 |journal=Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report |volume=54 |issue=51 & 52 |date=[[6 January]] [[2006]]| url=http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5451a2.htm| pages=1301-1305}}</ref> Approximately 95% of these are [[Aneuploidy#Trisomy|trisomy]] 21. Down syndrome occurs in all ethnic groups and among all economic classes. |

||

| + | [[Maternal age effect|Maternal age]] influences the risk of conceiving a baby with Down syndrome. At maternal age 20 to 24, the risk is 1/1490; at age 40 the risk is 1/60, and at age 49 the risk is 1/11.<ref name=Hook/> Although the risk increases with maternal age, 80% of children with Down syndrome are born to women under the age of 35,<ref>Estimate from {{cite web |title=National Down Syndrome Center |url=http://www.ndsccenter.org/resources/package3.php |accessdate = 2006-04-21}}</ref> reflecting the overall fertility of that age group. Other than maternal age, no other risk factors are known. There does not appear to be a paternal age effect. |

||

| − | == Education == |

||

| − | Cognitive development in children with Down syndrome is quite variable. Many can be successful in school, while others struggle. Because of this variability in expression of Down syndrome, it is important to evaluate children individually. The cognitive problems that are found among children with Down syndrome are also found among children without Down syndrome. This means that parents can take advantage of general programs that are offered through the schools or other means. |

||

| − | Children with Down syndrome have a wide range of abilities. It is not possible at birth to predict their capabilities. The identification of the best methods of teaching each particular child ideally begins soon after birth, through early intervention programs. |

||

| + | ==Prenatal screening== |

||

| − | Most children with Down syndrome are in the mild to moderate range of mental retardation. Emotional and social abilities follow a more normal path, moderated by whatever cognitive disability the child may have. Very early social and emotional development show about a one to three month delay on average. |

||

| + | Pregnant women can be screened for various complications in their pregnancy. Many standard prenatal screens can discover Down syndrome. [[Genetic counseling]] along with [[genetic testing]], such as [[amniocentesis]], [[chorionic villus sampling]] (CVS), or percutaneous umbilical blood sampling (PUBS) are usually offered to families who may have an increased chance of having a child with Down syndrome, or where normal prenatal exams indicate possible problems. Genetic screens are often performed on pregnant women older than 30 or 35. |

||

| − | Language skills show a difference between understanding speech and expressing speech. It is common for children with Down syndrome to need speech therapy to help with expressive language. |

||

| − | Fine motor skills often lag behind gross motor skills and can interfere with cognitive development. Occupational therapy can address these issues. |

||

| + | Amniocentesis and CVS are considered invasive procedures, in that they involve inserting instruments into the uterus, and therefore carry a small risk of causing fetal injury or miscarriage. There are several common non-invasive screens that can indicate a fetus with Down syndrome. These are normally performed in the late first trimester or early second trimester. Due to the nature of screens, each has a significant chance of a [[Type I and type II errors|false positive]], suggesting a fetus with Down syndrome when, in fact, the fetus does not have this genetic abnormality. Screen positives must be verified before a Down syndrome diagnosis is made. Common screening procedures for Down syndrome are given in Table 1. |

||

| − | Mainstreaming of children with Down syndrome is controversial. Mainstreaming is when students of differing abilities are placed in classes with their chronological peers. Children with Down syndrome do not age emotionally/socially and intellectually at the same rates as children without Down syndrome, so eventually the intellectual and emotional gap between children with and without Down syndrome widens. Complex thinking as required in sciences but also in history, the arts, and other subjects is often beyond their abilities, or achieved much later than in most children. Therefore, if they are to benefit from mainstreaming without feeling inferior most of the time, special adjustments must be made to the curriculum. |

||

| + | {| class="wikitable" |

||

| + | |+ Table 1: Common first and second trimester Down syndrome screens |

||

| + | |- |

||

| + | !Screen |

||

| + | !When performed (weeks [[gestation]]) |

||

| + | !Detection rate |

||

| + | ![[Type I and type II errors|False positive]] rate |

||

| + | !Description |

||

| + | |- |

||

| + | |Triple screen |

||

| + | |align="center"|15–20 |

||

| + | |align="center"|75% |

||

| + | |align="center"|8.5% |

||

| + | |This test measures the maternal serum [[alpha-fetoprotein|alpha feto protein]] (a fetal liver protein), [[estriol]] (a pregnancy hormone), and [[human chorionic gonadotropin]] (hCG, a pregnancy hormone).<ref name=quadrate>For a current estimate of rates, see {{cite journal| author=Benn, PA, J Ying, T Beazoglou, JFX Egan| journal=Prenatal Diagnosis| volume=21| issue=1| pages=46-51| title=Estimates for the sensitivity and false-positive rates for second trimester serum screening for Down syndrome and trisomy 18 with adjustments for cross-identification and double-positive results}} PMID 11180240</ref> |

||

| + | |- |

||

| + | |Quad screen |

||

| + | |align="center"|15–20 |

||

| + | |align="center"|79% |

||

| + | |align="center"|7.5% |

||

| + | |This test measures the maternal serum [[alpha-fetoprotein|alpha feto protein]] (a fetal liver protein), [[estriol]] (a pregnancy hormone), [[human chorionic gonadotropin]] (hCG, a pregnancy hormone), and high [[inhibin]]-Alpha (INHA).<ref name=quadrate/> |

||

| + | |- |

||

| + | |AFP/free beta screen |

||

| + | |align="center"|13–22 |

||

| + | |align="center"|80% |

||

| + | |align="center"|2.8% |

||

| + | |This test measures the [[alpha-fetoprotein|alpha feto protein]], produced by the fetus, and free beta hCG, produced by the [[placenta]]. |

||

| + | |- |

||

| + | |Nuchal translucency/free beta/PAPPA screen |

||

| + | |align="center"|10–13.5 |

||

| + | |align="center"|91%<ref name=nasalbone>Some practices report adding Nasal Bone measurements and increasing the detection rate to 95% with a 2% False Positive Rate.</ref> |

||

| + | |align="center"|5%<ref name=nasalbone>Some practices report adding Nasal Bone measurements and increasing the detection rate to 95% with a 2% False Positive Rate.</ref> |

||

| + | |Uses [[ultrasound]] to measure [[Nuchal translucency|Nuchal Translucency]] in addition to the freeBeta [[human chorionic gonadotropin|hCG]] and PAPPA (pregnancy-associate plasma protein A, {{OMIM|176385}}). NIH has confirmed that this first trimester test is more accurate than second trimester screening methods.<ref>NIH FASTER study (NEJM 2005 ('''353'''):2001). See also J.L. Simplson's editorial (NEJM 2005 ('''353'''):19).</ref> |

||

| + | |} |

||

| + | [[Image:Vessie T21.JPG|thumb|right|221px|Ultrasound of fetus with Down syndrome and [[megacystis]]]] |

||

| − | Children with Down syndrome can also be placed in classes with cognitive peers. After preschool, the difference in age makes this problematic. |

||

| + | Even with the best non-invasive screens, the detection rate is 90%–95% and the rate of false positive is 2%–5%. [[Type I and type II errors|False positive]]s can be caused by undetected multiple fetuses (very rare with the ultrasound tests), incorrect date of pregnancy, or normal variation in the proteins. |

||

| − | A danger in not mainstreaming is underestimating their abilities. This was more common in institutions, where Down syndrome children often failed to reach their potential despite being capable of much more, but this issue is very real and present in the modern school system as well. |

||

| − | Some European countries such as Germany and Denmark advise a two-teacher system, whereby the second teacher takes over a group of disabled children within the class. A popular alternative is cooperation between special education schools and mainstream schools. In cooperation, the core subjects are taught in separate classes, which neither slows down the non-disabled students nor neglects the disabled ones. Social activities, outings, and many sports and arts activities are performed together, as are all breaks and meals. |

||

| + | Confirmation of screen positive is normally accomplished with [[amniocentesis]]. This is an invasive procedure and involves taking [[amniotic fluid]] from the mother and identifying fetal cells. The lab work can take several weeks but will detect over 99.8% of all numerical chromosomal problems with a very low false positive rate. <!-- Although amniocentesis is very accurate, there are a significant number of pregnancies where the test is impossible to perform because of the position of the placenta. Please would someone add some statistics here!!! --><ref>{{cite web |title=Down syndrome |author=Fackler, A |url=http://health.yahoo.com/topic/children/baby/article/healthwise/hw167989 |accessdate = 2006-09-07}}</ref> |

||

| − | '''Alternative treatment''' |

||

| + | Due to the low incidence of Down syndrome, a vast majority of early screen positives are false.<ref>Assume the false positive rate is 2% (at the low end), the incidence of Down syndrome is 1/500 (on the high side) with 95% detection, and there is no [[ascertainment bias]]. Out of 100,000 screens, 200 will have Down syndrome, and the screen will detect 190 of them. From the 99,800 normal pregnancies, 1996 will be given a positive result. So, among the 2,186 positive test results, 91% will be false positives and 9% will be true positives.</ref> Since false positives typically prompt an amniocentesis to confirm the result, and the amniocentesis carries a small risk of inducing [[miscarriage]], there is a slight risk of miscarrying a healthy fetus. (The added miscarriage risk from an amniocentesis is traditionally quoted as 0.5%, but recent studies suggest that it may be considerably smaller (0.06% with a 95% CI of 0 to 0.5%).<ref>{{cite journal |title=Pregnancy loss rates after midtrimester amniocentesis |author=Eddleman, Keith A., ''et al'' |journal=Obstet Gynecol|year=2006|volume=108|issue=5|pages=1067-1072|url=http://www.greenjournal.org/cgi/content/short/108/5/1067 |accessdate = 2006-12-09}} PMID 17077226</ref>) |

||

| − | [[The Institutes for The Achievement of Human Potential|The Institutes for The Achievement of Human Potential]] (IAHP [http://www.iahp.org]) is a non-profit organization which treats children who have, as the IAHP terms it, "some form of brain injury," including children with Down syndrome. The IAHP offers a number of intellectual, physical, and physiological programs for children with neurological challenges. The approach of "Psychomotor Patterning" is not proven (see [http://www.quackwatch.org/01QuackeryRelatedTopics/patterning.html Psychomotor Patterning] for a negative viewpoint), and is considered [[Alternative medicine|alternative medicine]]. |

||

| + | A 2002 literature review of elective abortion rates found that 91–93% of pregnancies with a diagnosis of Down syndrome were terminated.<ref>{{cite journal| author=Caroline Mansfield, Suellen Hopfer, Theresa M. Marteau| title=Termination rates after prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome, spina bifida, anencephaly, and Turner and Klinefelter syndromes: a systematic literature review| year=1999| journal=Prenatal Diagnosis| volume=19| issue=9| pages=808-812| url=http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/cgi-bin/abstract/65500197/ABSTRACT}} PMID 10521836 This is similar to 90% results found by {{cite journal| title=Determinants of parental decisions after the prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome: Bringing in context| journal=American Journal of Medical Genetics| volume=93| issue=5| pages=410 - 416| year=1999| author=David W. Britt, Samantha T. Risinger, Virginia Miller, Mary K. Mans, Eric L. Krivchenia, Mark I. Evans}} PMID 10951466</ref> Physicians and ethicists are concerned about the ethical ramifications,<ref>{{cite journal| author=Glover, NM and Glover, SJ| title=Ethical and legal issues regarding selective abortion of fetuses with Down syndrome| journal=Ment. Retard.| year=1996| volume=34| issue=4| pages=207-214| id=PMID 8828339}}</ref> with some commentators calling it "[[eugenics]] by abortion".<ref>{{cite journal |last=Will |first=George |title=Eugenics By Abortion: Is perfection an entitlement? |date=2005-04-14 |journal=Washington Post |pages=A37 |url=http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A51671-2005Apr13.html |accessdate = 2006-07-03}}</ref> Many members of the [[disability rights]] movement "believe that public support for prenatal diagnosis and abortion based on disability contravenes the movement's basic philosophy and goals."<ref>{{cite journal |author=Erik Parens and Adrienne Asch |title=Disability rights critique of prenatal genetic testing: Reflections and recommendations |year=2003 |journal=Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews |volume=9 |issue=1 |page=40-47 |url=http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/cgi-bin/abstract/102531130/ABSTRACT| accessdate = 2006-07-03}} PMID 12587137</ref> |

||

| − | == Health == |

||

| − | Individuals with Down syndrome are at risk for various medical conditions. There is no way to predict what conditions they will have, if any. In addition, all these medical conditions can be exhibited by individuals without Down syndrome. It is important to keep these medical risks in mind while undergoing wellness checkups. The following links point to health flowcharts that can help parents with normal checkups [http://www.ds-health.com/ 6]. |

||

| − | * [http://www.ds-health.com/recordsheet1.htm Children Birth to Age 12] |

||

| − | * [http://www.ds-health.com/recordsheet2.htm Children Age 13 to Adulthood] |

||

| + | ==Cognitive development== |

||

| − | A partial list of risks is given below. Risks run from 80% (hearing deficits) to 50% (congenital heart defects) to 20% (hypothyroidism) to rare but significantly increased risks (Leukemia). |

||

| + | [[Cognitive development]] in children with Down syndrome is quite variable. It is not possible at birth to predict their capabilities, nor are the number or appearance of physical features predictive of future ability. The identification of the best methods of teaching each particular child ideally begins soon after birth through early intervention programs.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ndss.org/content.cfm?fuseaction=NwsEvt.Article&article=1558|title=New Parent Guide|publisher=National Down Syndrome Society|accessdate = 2006-05-12}} Also {{cite web |url=http://www.downsed.org/research/projects/early-intervention |title=Research projects - Early intervention and education |accessdate = 2006-06-02}}</ref> Since children with Down syndrome have a wide range of abilities, success at school can vary greatly, which stresses the importance of evaluating children individually. The cognitive problems that are found among children with Down syndrome can also be found among typical children. Therefore, parents can use general programs that are offered through the schools or other means. |

||

| − | * [[Congenital heart disease|Congenital heart defects]] |

||

| − | * Increased susceptibility to infection |

||

| − | * Muscular/Skeletal abnormalities, including generally poor muscle tone. |

||

| − | * Respiratory problems |

||

| − | * [[sleep apnea|Obstructive sleep apnea]] |

||

| − | * [[Gastroesophageal reflux disease|Gastroesophageal reflux disease]] |

||

| − | * Obstructed digestive tracts |

||

| − | * [[Thyroid]] dysfunctions ([[hypothyroidism]]) |

||

| − | * [[Acute myelogenous leukemia|Acute myeloid leukemia]], although their survival and relapse rate is much better than average |

||

| − | * [[Infertility]] (nearly absolute in males, fertility in females is possible) |

||

| − | * Hearing deficits |

||

| − | * Eye problems ([[cataract]]s, [[strabismus]], near and far sightedness) |

||

| − | * [[Alzheimer's disease]] |

||

| + | Language skills show a difference between understanding speech and expressing speech. It is common for children with Down syndrome to need speech therapy to help with expressive language.<ref>{{cite journal| author =Bird, G. and S. Thomas| year =2002| title = Providing effective speech and language therapy for children with Down syndrome in mainstream settings: A case example | journal =Down Syndrome News and Update| volume =2| issue =1| pages =30-31}} Also, {{cite book| last =Kumin| first=Libby| editor=Hassold, T.J.and D. Patterson| title =Down Syndrome: A Promising Future, Together| year =1998| publisher =Wiley-Liss| location =New York| chapter = Comprehensive speech and language treatment for infants, toddlers, and children with Down syndrome}}</ref> [[Fine motor skill]]s are delayed<ref>{{cite web| title=Development of Fine Motor Skills in Down Syndrome| url=http://www.about-down-syndrome.com/fine-motor-skills-in-down-syndrome.html| accessdate = 2006-07-03}}</ref> and often lag behind [[gross motor skill]]s and can interfere with cognitive development. [[Occupational therapy]] can address these issues.<ref>{{cite web |author = M. Bruni|url=http://www.ds-health.com/occther.htm| title=Occupational Therapy and the Child with Down Syndrome|accessdate = 2006-06-02}}</ref> |

||

| − | There is some evidence that individuals with Down syndrome have a much lower rate of lung cancer than others, as is expected for all cancers caused by [[Tumor suppressor gene|tumor suppressor genes]]. |

||

| + | In education, [[Mainstreaming in education|mainstreaming]] of children with Down syndrome is becoming less controversial in many countries. For example, there is a presumption of mainstream in many parts of the UK. Mainstreaming is the process whereby students of differing abilities are placed in classes with their chronological peers. Children with Down syndrome may not age emotionally/socially and intellectually at the same rates as children without Down syndrome, so over time the intellectual and emotional gap between children with and without Down syndrome may widen. Complex thinking as required in sciences but also in history, the arts, and other subjects can often be beyond the abilities of some, or achieved much later than in other children. Therefore, children with Down syndrome may benefit from mainstreaming provided that some adjustments are made to the curriculum.<ref>{{cite web|author=S.E.Armstrong|url=http://www.altonweb.com/cs/downsyndrome/index.htm?page=ndssincl.html|title=Inclusion: Educating Students with Down Syndrome with Their Non-Disabled Peers|accessdate = 2006-05-12}} Also, see {{cite web|url=http://www.altonweb.com/cs/downsyndrome/index.htm?page=bosworth.html| title=Benefits to Students with Down Syndrome in the Inclusion Classroom: K-3| author=Debra L. Bosworth| accessdate = 2006-06-12}} Finally, see a survey by NDSS on inclusion, {{cite web|url=http://www.altonweb.com/cs/downsyndrome/index.htm?page=wolpert.html| title=The Educational Challenges Inclusion Study| author=Gloria Wolpert| year=1996| publisher=National Down Syndrome Society| accessdate = 2006-06-28}}</ref> |

||

| − | As with all risks, this does not mean that everyone with Down syndrome will get these diseases, nor that an individual will get '''any''' of them. The concentration on wellness in individuals with Down syndrome and increased medical technology has vastly improved the length and quality of life. Current estimates ([http://www.ndss.org/content.cfm?fuseaction=InfoRes.HlthArticle&article=19 7]) give life expectancy in the United States as 55 years, compared to 77 years for the population in general. This life expectancy is a tremendous increase in recent years. |

||

| + | Some European countries such as [[Germany]] and [[Denmark]] advise a two-teacher system, whereby the second teacher takes over a group of children with disabilities within the class. A popular alternative is cooperation between [[special school]]s and mainstream schools. In cooperation, the core subjects are taught in separate classes, which neither slows down the typical students nor neglects the students with disabilities. Social activities, outings, and many sports and arts activities are performed together, as are all breaks and meals.<ref>There are many such programs. One is described by Action Alliance for Children, {{web cite|author=K. Flores| url=http://www.4children.org/news/103spec.htm|title=Special needs, "mainstream" classroom|accessdate = 2006-05-13}} Also, see {{web cite|author=Flores, K.|url=http://www.4children.org/pdf/103spec.pdf|title=Special needs, "mainstream" classroom|accessdate = 2006-05-13}}</ref> |

||

| − | == Medical research == |

||

| − | Of the inborn differences that affect intellectual capacity, Down syndrome is the most prevalent and best studied. Down syndrome is a term used to encompass a number of [[genetic disorder]]s of which [[Aneuploidy#Trisomy|trisomy]] 21 is the most frequent (95% of cases). Discovered by the Parisian physician Jerome Lejeune in 1959, Trisomy 21 is the existence of the third copy of the [[chromosome]] 21 in cells throughout the body of the affected person. Other Down syndrome disorders are based on the duplication of the same subset of [[gene]]s (e.g., various translocations of chromosome 21). Depending on the actual [[etiology]], the degree of impairment may range from mild to severe. In rare cases trisomy 21 is present in some cell lines but not all, due to an anomalous early cell division in the [[zygote]]. There is evidence that this variant, called '''mosaic Down syndrome''', may produce less developmental delay, on average, than full trisomy 21. |

||

| − | [http://www.imdsa.com] |

||

| − | [http://www.ds-health.com/mosaic.htm 3] |

||

| + | ==Health== |

||

| − | Trisomy 21 results in over-[[expression of genes]] located on chromosome 21. One of these is the [[superoxide dismutase]] gene. Some (but not all) studies have shown that the activity of the superoxide dismutase enzyme ([[SOD]]) is elevated in Down syndrome. SOD converts [[oxygen radicals]] to [[hydrogen peroxide]] and [[water]]. Oxygen radicals produced in cells can be damaging to cellular structures, hence the important role of SOD. However, the hypothesis says that once SOD activity increases disproportionately to [[enzyme]]s responsible for removal of hydrogen peroxide (e.g., [[glutathione peroxidase]]), the cells will suffer from a peroxide damage. Some scientists believe that the treatment of Down syndrome [[neuron]]s with [[free radical]] scavengers can substantially prevent neuronal degeneration. Oxidative damage to neurons results in rapid [[human brain|brain]] aging similar to that of [[Alzheimer's disease]]. |

||

| + | {{main|Health aspects of Down syndrome}} |

||

| + | The medical consequences of the extra genetic material in Down syndrome are highly variable and may affect the function of any organ system or bodily process. The health aspects of Down syndrome encompass anticipating and preventing effects of the condition, recognizing complications of the disorder, managing individual symptoms, and assisting the individual and his/her family in coping and thriving with any related disability or illnesses.<ref>{{cite journal| author=American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Genetics| title=American Academy of Pediatrics: Health supervision for children with Down syndrome| journal=Pediatrics| year=2001| month=Feb| volume=107| issue=2| pages=442-449| id=PMID 11158488}}</ref> |

||

| + | |||

| + | The most common manifestations of Down syndrome are the characteristic facial features, cognitive impairment, [[congenital heart disease]], hearing deficits, [[short stature]], [[thyroid]] disorders, and [[Alzheimer's disease]]. Other less common serious illnesses include [[leukemia]], [[immune deficiency|immune deficiencies]], and [[epilepsy]]. However, health benefits of Down syndrome include greatly reduced incidence of many common malignancies except leukemia and testicular cancer<ref>Yang Q, Rasmussen SA, Friedman JM. [http://www.ds-health.com/abst/a0205.htm Mortality associated with Down's syndrome in the USA from 1983 to 1997: a population-based study.] ''Lancet'' 2002 [[23 March]];359(9311):1019-25. PMID 11937181</ref> - although it is, as yet, unclear whether the reduced incidence of various fatal cancers among people with Down syndrome is as a direct result of tumor-suppressor genes on chromosome 21, because of reduced exposure to [[environmental factor]]s that contribute to cancer risk, or some other as-yet unspecified factor. Down syndrome can result from several different genetic mechanisms. This results in a wide variability in individual symptoms due to complex gene and environment interactions. Prior to birth, it is not possible to predict the symptoms that an individual with Down syndrome will develop. Some problems are present at birth, such as certain heart malformations. Others become apparent over time, such as epilepsy. |

||

| + | These factors can contribute to a significantly shorter lifespan for people with Down syndrome. One study, carried out in the [[United States]] in 2002, showed an average lifespan of 49 years, with considerable variations between different ethnic and socio-economic groups.<ref name="lifespan">{{cite news |first = Emma |

||

| − | Another chromosome 21 gene that might predispose Down syndrome individuals to develop Alzheimer's pathology is the gene that encodes the precursor of the [[amyloid protein]]. Neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid plaques are commonly found in both Down syndrome and Alzheimer's individuals. Layer II of the [[entorhinal cortex]] and the subiculum, both critical for [[memory consolidation]], are among the first affected by the damage. A gradual decrease in the number of nerve cells throughout the [[cortex (neuroanatomy)|cortex]] follows. A few years ago, [[Johns Hopkins University|Johns Hopkins]] scientists created a genetically engineered [[mus musculus|mouse]] called Ts65Dn (segmental trisomy 16 mouse) as an excellent model for studying the Down syndrome. Ts65Dn mouse has genes on chromosomes 16 that are very similar to the human chromosome 21 genes. With this [[animal model]], the exact causes of Down syndrome neurological symptoms may soon be elucidated. Naturally, Ts65Dn research is also likely to highly benefit Alzheimer's research. |

||

| + | |last = Young |

||

| + | |authorlink = |

||

| + | |author = |

||

| + | |coauthors = |

||

| + | |title = Down's syndrome lifespan doubles |

||

| + | |url = http://www.newscientist.com/article.ns?id=dn2073 |

||

| + | |format = |

||

| + | |work = New Scientist |

||

| + | |publisher = |

||

| + | |pages = |

||

| + | |page = |

||

| + | |date = 2002-03-22 |

||

| + | |accessdate = 2006-10-14 |

||

| + | |language = }} |

||

| + | </ref> |

||

| + | Fertility amongst both males and females is reduced,<ref name="fertility">{{cite journal |

||

| − | While there are a number of commercially promoted dietary supplements on the market, especially in the USA, mainly involving various combinations of vitamins and minerals, none of these have been medically approved for use in the UK for the mass treatment of people with Down syndrome and none appear to lead to any proven lasting benefits. All remain highly controversial. |

||

| + | | author = Ying-Hui H. Hsiang, Gary D. Berkovitz, Gail L. Bland, Claude J. Migeon, Andrew C. Warren, John M. Opitz, James F. Reynolds |

||

| + | | title = Gonadal function in patients with Down syndrome |

||

| + | | journal = American Journal of Medical Genetics |

||

| + | | volume = 27 |

||

| + | | issue = 2 |

||

| + | | pages = 449--458 |

||

| + | | publisher = Wiley-Liss, Inc. |

||

| + | | date = 1987 |

||

| + | | url = http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.1320270223 |

||

| + | | id = 10.1002/ajmg.1320270223 |

||

| + | | format = |

||

| + | | accessdate = }}</ref> with only three recorded instances of males with Down syndrome fathering children.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Sheridan R, Llerena J, Matkins S, Debenham P, Cawood A, Bobrow M |title=Fertility in a male with trisomy 21 |journal=J Med Genet |volume=26 |issue=5 |pages=294-8 |year=1989 |pmid=2567354}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Pradhan M, Dalal A, Khan F, Agrawal S |title=Fertility in men with Down syndrome: a case report |journal=Fertil Steril |volume=86 |issue=6 |pages=1765.e1-3 |year=2006 |pmid=17094988}}</ref> |

||

| − | == |

+ | ==Genetic research== |

| + | {{main|Research of Down syndrome-related genes}} |

||

| − | {{section-stub}} |

||

| + | Down syndrome disorders are based on having too many copies of the [[gene]]s located on chromosome 21. In general, this leads to an overexpression of the genes.<ref>{{cite journal| author=R Mao, CL Zielke, HR Zielke, J Pevsner| title=Global up-regulation of chromosome 21 gene expression in the developing Down syndrome brain| journal=[[Genomics]]| year=2003| volume=81| issue=5| pages=457-467| url=http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6WG1-487KHTJ-1&_coverDate=05%2F31%2F2003&_alid=422057371&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_qd=1&_cdi=6809&_sort=d&view=c&_acct=C000050221&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=10&md5=9ec6c22133f1645bad48a10a8fb14485}} PMID 12706104</ref><ref>{{cite journal| author=Rong Mao, X Wang, EL Spitznagel, et al| title=Primary and secondary transcriptional effects in the developing human Down syndrome brain and heart| journal=Genome Biology| year=2005| volume=6| issue=13| pages=R107| url=http://www.pubmedcentral.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract&artid=1414106}} PMID 16420667</ref> Understanding the genes involved may help to target medical treatment to individuals with Down syndrome. It is estimated that chromosome 21 contains 200 to 250 genes.<ref name="Leshin">{{cite web |author=Leshin, L. |year=2003 |url=http://www.ds-health.com/trisomy.htm |title=Trisomy 21: The Story of Down Syndrome |accessdate = 2006-05-21}}</ref> Recent research has identified a region of the chromosome that contains the main genes responsible for the pathogenesis of Down syndrome,<ref>{{cite journal| author=Zohra Rahmani, Jean-Louis Blouin, Nicole Créau-Goldberg, Paul C. Watkins, Jean-François Mattei, Marc Poissonnier, Marguerite Prieur, Zoubida Chettouh, Annie Nicole, Alain Aurias, Pierre-Marie Sinet, Jean-Maurice Delabar| title=Down syndrome critical region around D21S55 on proximal 21q22.3| journal=[[American Journal of Medical Genetics]]| year=2005| volume=37| issue=S2| pages=98-103| url=http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/cgi-bin/abstract/110515872/ABSTRACT}} PMID 2149984</ref> located proximal to 21q22.3. The search for major genes involved in Down syndrome characteristics is normally in the region 21q21–21q22.3. |

||

| − | === Pregnant women with a diagnosis of Down syndrome === |

||

| − | {{section-stub}} |

||

| + | Recent use of [[genetically modified organism|transgenic]] [[mouse|mice]] to study specific genes in the Down syndrome critical region has yielded some results. [[Amyloid beta|APP]]<ref>{{OMIM|104760}}, gene [[Locus (genetics)|located]] at [[Chromosome 21 (human)|21]][http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Omim/getmap.cgi?l104760 q21]. Retrieved on [[2006-12-05]].</ref> is an [[Amyloid beta]] A4 precursor protein. It is suspected to have a major role in cognitive difficulties.<ref>{{cite web |title=Down syndrome traced to one gene |publisher=''The Scientist'' |first=Chandra |last= Shekhar |url=http://www.the-scientist.com/news/display/23869/ |date=2006-07-06 |accessdate = 2006-07-11}}</ref> Another gene, ETS2<ref>{{OMIM|164740}}, located at [[Chromosome 21 (human)|21]] [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Omim/getmap.cgi?l164740 q22.3]. Retrieved on [[2006-12-05]].</ref> is Avian Erythroblastosis Virus E26 Oncogene Homolog 2. Researchers have "demonstrated that overexpression of ETS2 results in [[apoptosis]]. Transgenic mice overexpressing ETS2 developed a smaller thymus and lymphocyte abnormalities, similar to features observed in Down syndrome."<ref>{{cite web |author=OMIM, NIH |url=http://www3.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/dispomim.cgi?id=164740 |title=V-ETS Avian Erythroblastosis virus E26 Oncogene Homolog 2 |accessdate = 2006-06-29}}</ref> |

||

| − | === Parents of children with Down syndrome === |

||

| − | {{section-stub}} |

||

| − | === Individuals with Down syndrome === |

||

| − | {{section-stub}} |

||

| + | ==Sociological and cultural aspects== |

||

| − | == Down syndrome's sociology == |

||

| + | [[Disability|Advocates]] for people with Down syndrome point to various factors, such as special education and parental support groups, that make life easier for parents. There are also strides being made in education, housing, and social settings to create environments which are accessible and supportive to people with Down syndrome. In most developed countries, since the early twentieth century many people with Down syndrome were housed in institutions or colonies and excluded from society. However, since the early 1960s parents and their organisations (such as [http://www.mencap.org.uk/ MENCAP] ), educators and other professionals have generally advocated a policy of inclusion,<ref>{{cite book |title=Inclusion: Educating Students with Down Syndrome with Their Non-Disabled Peers |publisher=National Down Syndrome Society |url=http://www.ndss.org/content.cfm?fuseaction=InfoRes.SchEduarticle&article=571 |accessdate = 2006-05-21}}</ref> bringing people with any form of mental or physical disability into general society as much as possible. In many countries, people with Down syndrome are educated in the normal school system; there are increasingly higher-quality opportunities to mix special education with regular education settings. |

||

| − | {{NPOV-section}} |

||

| − | Advocates for people with Down syndrome stress that affected individuals have the same [[human right]]s and [[emotion]]s as any other human beings. Down syndrome is considered grounds for [[abortion]] in an increasing number of countries. The number of children born with Down syndrome is decreasing due to the large number of abortions following an early diagnosis of Down syndrome during pregnancy. In a hearing before the German Parliament, doctors stated that 90% of all fetuses [[prenatal diagnosis|prenatally diagnosed]] with Down syndrome are aborted. This number is consistent with the official statistics, wherein 1500 children with Down syndrome should, statistically, have been born per year (at a prevalence rate of 1:600), but only 63 per annum were listed in the 1995 birth register. In the United States numbers are reported to fluctuate between 70-80% of all women diagnosed during pregnancy will opt to terminate the pregnancy because of Down syndrome. Advocates for Down syndrome state this is similar to eugenics and is often based in fear of the unknown. Further, they argue that many parents given the information of a Down diagnosis are not fully informed on the wide range of the disorder or that there is an adoption waiting list full of people who wish to have a child with Down syndrome. |

||

| + | Despite this change, reduced abilities of people with Down syndrome can pose a challenge to parents and families. Although living with family is preferable to institutionalization for most people, people with Down syndrome often encounter patronizing attitudes and discrimination in the wider community. In the past decade, many{{Fact|date=February 2007}} couples with Down syndrome have married and started families, overcoming stereotypes associated with this condition.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} [this contradicts earlier statement regarding fertility of just 3 recorded cases of men with Down's syndrome becoming fathers] |

||

| − | Advocates for people with Down syndrome also point to various factors, such as special education and parental support groups, that make life easier for parents of children with the disorder. There are also great strides being made in education, housing, and social settings to create "Down-friendly" environments. It is argued that many only view people with Down's in the ways of the past, limiting them to sub-standard possibilities in life and ignoring their very real social needs. In most developed countries, since the early 20th century many people with Down syndrome were housed in "mental subnormality" institutions or colonies and excluded from society. However, in the 21st century there is a moving change among parents, educators and other professionals generally advocate a policy of "inclusion", bringing people with any form of mental or physical disability into general society as much as possible. In many countries, people with Down syndrome are educated in the normal school system and there are increasingly higher quality opportunties to mix "special" education with regular education settings. |

||

| + | The first [[World Down Syndrome Day]] was held on [[21 March]] [[2006]]. The day and month were chosen to correspond with 21 and trisomy respectively. It was proclaimed by [[Down Syndrome International]].<ref>{{cite web| url=http://www.worlddownsyndromeday.org|title=World Down Syndrome Day| accessdate = 2006-06-02}}</ref> In the United States, the National Down Syndrome Society observes Down Syndrome Month every October as "a forum for dispelling stereotypes, providing accurate information, and raising awareness of the potential of individuals with Down syndrome."<ref>[http://www.ndss.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=1962&Itemid=233 National Down Syndrome Society]</ref> In [[South Africa]], Down Syndrome Awareness Day is held every October 20.<ref>[http://www.downsyndrome.org.za/main.aspx?artid=54 Down Syndrome South Africa]</ref> |

||

| − | Despite this change, the reduced abilities of people with Down syndrome pose a challenge to their parents and families. While living with their parents is preferable to institutionalization for most adults with Down syndrome, they often encounter patronising attitudes and discrimination in the wider community. Social views of persons with Down still rest on the pre-intervention days when babies were immediately isolated and lacked proper social interaction and stimulation. The case is there are wide ranges of ability among persons living with Down and many are capable of living "normal" lives with some degree of assistance just as other disabled persons may. This means people with Down syndrome are able to run their own household, apply for a regular job, get a driver's licence and take care of insurances, etc, by themselves. It is preferable to institutional living, the 1980's and 1990's experiments with group homes were not especially successful, and a number of new models are emerging. In the past few years the independent (supported) living model has found favour with UK governments. With Direct Payments, some people are able to employ their own staff. Individuals can take on their own tenancy,or shared ownership and receive support from a skilled caregiver in organizing their own life, studies, career, and outside interests. For an example of a young woman using Direct Payments for this, see [http://caslater.freeservers.com/Karensflat.htm] |

||

| + | ==History== |

||

| − | == Notable individuals == |

||

| − | + | {{main|History of Down syndrome}} |

|

| + | English physician [[John Langdon Down]] first characterized Down syndrome as a distinct form of mental retardation in 1862, and in a more widely published report in 1866 entitled "Observations on an ethnic classification of idiots".<ref>{{cite journal| author=Down, J.L.H.| year=1866| title=Observations on an ethnic classification of idiots| journal=Clinical Lecture Reports, London Hospital| volume=3| pages=259-262| url=http://www.neonatology.org/classics/down.html| accessdate = 2006-07-14}} For a history of the disorder, see {{cite book | title= John Langdon Down, 1828-1896 | author=OC Ward |publisher=Royal Society of Medicine Press | id=ISBN 1-85315-374-5|year = 1998}} or {{cite web| last=Conor| first=Ward |url =http://www.intellectualdisability.info/values/history_DS.htm| title =John Langdon Down and Down's syndrome (1828 - 1896)| accessdate = 2006-06-02}}</ref> Due to his perception that children with Down syndrome shared physical facial similarities ([[epicanthal fold]]s) with those of [[Johann Friedrich Blumenbach|Blumenbach's Mongolian race]], Down used terms such as ''mongolism'' and ''Mongolian idiocy''.<ref>{{cite journal|Author =Conor, W.O.| year =1999| title =John Langdon Down: The Man and the Message| journal =Down Syndrome Research and Practice| volume =6| issue =1| pages =19-24| url =http://www.down-syndrome.info/library/periodicals/dsrp/06/1/019/DSRP-06-1-019-EN-GB.htm| accessdate = 2006-06-02}}</ref> [[Idiot|Idiocy]] was a medical term used at that time to refer to a severe degree of intellectual impairment. Down wrote that mongolism represented "retrogression," the appearance of [[Mongoloid]] traits in the children of allegedly more advanced Caucasian parents. |

||

| − | * [[Stephane Ginnsz]], actor (''[[Duo (film)]]'') First actor with Down syndrome in the lead part of a motion picture. |

||

| − | * [[Chris Burke (actor)|Chris Burke]], actor (''[[Life Goes On]]'') and autobiographer |

||

| − | * [[Andrea Friedman]], actor (''[[Life Goes On]]''), guest appearances on many other shows |

||

| − | * [[Pascal Duquenne]], actor (''[[Le Huitième Jour]]'' aka The Eighth Day, ''[[Toto le héros]]'' aka Toto the Hero) |

||

| − | * [[Anne de Gaulle]] ([[1928]]-[[1948]]), daughter of [[Charles de Gaulle]] |

||

| − | * [[Miguel Tomasin]], singer with Argentinian avant-rock band [[Reynols]] |

||

| + | By the 20<sup>th</sup> century, "Mongolian idiocy" had become the most recognizable form of mental retardation. Most individuals with Down syndrome were [[institutionalization|institutionalized]], few of the associated medical problems were treated, and most died in infancy or early adult life. With the rise of the [[eugenics]] movement, 33 of the (then) 48 [[U.S. state]]s and several countries began programs of involuntary sterilization of individuals with Down syndrome and comparable degrees of disability. The ultimate expression of this type of public policy was the [[Nazi Germany|German]] [[euthanasia]] program [[T-4 Euthanasia Program|"Aktion T-4"]], begun in 1940. Court challenges and public revulsion led to discontinuation or repeal of such programs during the decades after [[World War II]]. |

||

| − | == Down syndrome in fiction == |

||

| − | * [[Bret Lott]]: "[[Jewel (book)|Jewel]]" |

||

| − | * [[Morris West]]: "[[The Clowns of God]]" |

||

| − | * [[Bernice Rubens]]: ''[[A Solitary Grief]]'' |

||

| − | * [[Emily Perl Kingsley]]: "[[Welcome to Holland]]" |

||

| − | * [[The Kingdom (television)|The Kingdom]] and its American counterpart, ''[[Kingdom Hospital]]'' |

||

| − | * [[Elizabeth Laird]]: ''Red Sky in the Morning'' |

||

| − | * [[Stephen King]]: "[[Dreamcatcher (novel)|Dreamcatcher]]" |

||

| − | * [[Dean Koontz]]: "[[The Bad Place (novel)|The Bad Place]]" |

||

| − | * [[Alex Ginnsz]]: "[[Duo (film)|Duo]]" |

||

| − | * [[Flannery O'Connor]]: ''[[The Violent Bear It Away]]'' |

||

| − | * [[Benjamin Compson]]: ''[[The Sound and the Fury]]'' |

||

| + | Until the middle of the 20th century, the cause of Down syndrome remained unknown. However, the presence in all races, the association with older maternal age, and the rarity of recurrence had been noticed. Standard medical texts assumed it was caused by a combination of inheritable factors which had not been identified. Other theories focused on injuries sustained during birth.<ref>{{cite book |author=Warkany, J. |title=Congenital Malformations |location=Chicago |publisher=Year Book Medical Publishers, Inc |date=1971 |pages=313-314 |id=ISBN 0-8151-9098-0}}</ref> |

||

| − | == Sources == |

||

| − | * Hook EB. Rates of chromosomal abnormalities at different maternal ages. ''Obstet Gynecol'' 1981;58:282. |

||

| − | * [http://www.intellectualdisability.info/values/history_DS.htm 2:www.intellectualdisability.info/values/history_DS.htm] |

||

| − | * [http://www.ds-health.com/mosaic.htm 3:www.ds-health.com/mosaic.htm] |

||

| − | * [http://www.newscientist.com/news/news.jsp?id=ns99992073 4:www.newscientist.com/news/news.jsp?id=ns99992073] |

||

| − | * [http://www.cdss.ca/en/about_us/policies_and_statements/down_syndrome.htm 5:www.cdss.ca/en/about_us/policies_and_statements/down_syndrome.htm] |

||

| − | * [http://www.ds-health.com/ 6:www.ds-health.com] |

||

| − | * [http://www.ndss.org/content.cfm?fuseaction=InfoRes.HlthArticle&article=19 7:www.ndss.org/content.cfm?fuseaction=InfoRes.HlthArticle&article=19] |

||

| + | With the discovery of [[karyotype]] techniques in the 1950s, it became possible to identify abnormalities of chromosomal number or shape. In 1959, [[Jérôme Lejeune|Professor Jérôme Lejeune]] discovered that Down syndrome resulted from an extra chromosome.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.fondationlejeune.org/eng/Content/Fondation/professeurlj.asp |title=Jérôme Lejeune Foundation |accessdate = 2006-06-02}}</ref> The extra chromosome was subsequently labeled as the 21st, and the condition as [[Aneuploidy#Trisomy|trisomy]] [[Chromosome 21|21]]. |

||

| − | == Further reading == |

||

| − | * ''Down Syndrome: The Facts.'' (1997), Selikowitz, M.(2nd ed.). Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press. |

||

| − | * ''Down Syndrome: A Promising Future, Together.'' (1999), Hassold, T. J. and Patterson, D. (Eds.). New York, NY, USA: Wiley Liss. |

||

| − | * ''Count us in - Growing up with Down syndrome.'' (1994) Kingsley, J. and Levitz, M. (1994) San Diego, CA, USA: Harcourt Brace. |

||

| − | * ''Medical and Surgical Care for Children with Down Syndrome: A Guide for Parents.'' (1995) Van Dyke, D. C., Mattheis, P. J., Schoon Eberly, S., and Williams, J. Bethesda, MD, USA: Woodbine House. |

||

| − | * ''Adolescents with Down Syndrome: Toward a More Fulfilling Life.'' (1997) Pueschel, S. M. and Sustrova M. (Eds.) Baltimore, MA, USA: Paul H. Brookes Pub. |

||

| − | * ''Living with Down syndrome'' (2000), Buckley, S. Portsmouth, UK: The Down Syndrome Educational Trust. Also available online: http://www.down-syndrome.info/library/dsii/01/01/ |

||

| − | * ''Expecting Adam'' (1999), Beck, Martha N. Ph.D., New York, NY, USA: Berkley Books. |

||

| − | *''Choosing Naia: A Family's Journey'' (2002), Zuckoff, Mitchell, New York, NY, USA: Beacon Press. |

||

| + | In 1961, nineteen geneticists wrote to the editor of ''[[The Lancet]]'' suggesting that ''Mongolian idiocy'' had "misleading connotations," had become "an embarrassing term," and should be changed.<ref>{{cite journal |first=Allen |last=Gordon |coauthors=C.E. Benda, J.A. Böök, C.O. Carter, C.E. Ford, E.H.Y. Chu, E. Hanhart, George Jervis, W. Langdon-Down, J. Lejeune, H. Nishimura, J. Oster, L.S. Penrose, P.E. Polani, Edith L. Potter, Curt Stern, R. Turpin, J. Warkany, and Herman Yannet |year=1961 |title=Mongolism (Correspondence) |journal=[[The Lancet]] |pages=775 |volume=1 |issue=7180}}</ref> ''The Lancet'' supported ''Down's Syndrome''. The [[World Health Organization]] (WHO) officially dropped references to ''mongolism'' in 1965 after a request by the Mongolian delegate.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Howard-Jones |first=Norman| date=1979 |title=On the diagnostic term "Down's disease"| journal=Medical History |volume=23 |issue=1 |pages=102-104 |id=PMID 153994}}</ref> |

||

| − | == External links == |

||

| + | |||

| − | * [http://www.cdss.ca Canadian Down Syndrome Society] |

||

| + | In 1975, the United States [[National Institutes of Health]] convened a conference to standardize the nomenclature of malformations. They recommended eliminating the possessive form: "The possessive use of an eponym should be discontinued, since the author neither had nor owned the disorder."<ref>A planning meeting was held on [[20 March]] [[1974]], resulting in a letter to ''The Lancet''.{{cite journal |year=1974 |title=Classification and nomenclature of malformation (Discussion) |journal=[[The Lancet]] |pages=798 |volume=303 |issue=7861}} The conference was held [[10 February]]-[[11 February]] [[1975]], and reported to ''The Lancet'' shortly afterward.{{cite journal |year=1975 |title=Classification and nomenclature of morphological defects (Discussion) |journal=[[The Lancet]] |pages=513 |volume=305 |issue=7905}}</ref> Although both the possessive and non-possessive forms are used in the general population, Down syndrome is the accepted term among professionals in the USA, [[Canada]] and other countries; Down's syndrome is still used in the United Kingdom and other areas.<ref name=name>{{cite web |last=Leshin |first=Len| date=2003 |url=http://www.ds-health.com/name.htm |title=What's in a name |accessdate = 2006-05-12}}</ref> |

||

| − | * [http://www.imdsa.com International Mosaic Down Syndrome Association] |

||

| + | |||

| − | * [http://www.alldownsyndrome.com AllDownSyndrome.com] |

||

| + | |||

| − | * [http://www.duo.agprods.com The Official Site of the Film Duo, starring Stephane Ginnsz] |

||

| + | ==See also== |

||

| − | * [http://www.stephane.ginnsz.com Stephane Ginnsz, Actor with Down Syndrome - Official Website] |

||

| + | *[[Dementia affecting people with Downs syndrome]] |

||

| − | * [http://www.downsed.org/about/overview/key-facts-EN-GB.htm Key facts about Down syndrome] |

||

| + | *[[Genetic counseling: Down Syndrome - Trisomy 21-]] |

||

| − | * [http://www.down-syndrome.info/library/dsii/01/01/DSii-01-01-EN-GB.htm Living with Down syndrome (Online book)] |

||

| + | *[[Moderate mental retardation]] |

||

| − | * [http://www.down-syndrome.info/ Down Syndrome Information web site] |

||

| + | *[[Trisomy 21]] |

||

| − | * [http://www.ndss.org/ National Down Syndrome Society web site] |

||

| + | |||

| − | * [http://www.ndsccenter.org/ National Down Syndrome Congress web site] |

||

| + | ==References== |

||

| − | * [http://www.downsyn.com/ Down Syndrome: For New Parents] |

||

| + | {{reflist|2}} |

||

| − | * [http://www.downsed.org/ The Down Syndrome Educational Trust web site] |

||

| + | *Aparicio, M. T. S., & Balana, J. M. (2003). Social Early Stimulation of Trisomy-21 Babies: Early Child Development and Care Vol 173(5) Oct 2003, 557-561. |

||

| − | * [http://www.dsrf.org/ Down Syndrome Research Foundation web site] |

||

| + | |||

| − | * [http://www.dsa-uk.com/ UK Down's Syndrome Association web site] |

||

| + | ==Bibliography== |

||

| − | * [http://www.down-syndrome.info/library/periodicals/dsrp/06/1/019/DSRP-06-1-019-EN-GB.htm Information on the original description of Down syndrome] |

||

| + | * {{cite book |

||

| − | * [http://www.ericdigests.org/pre-9211/down.htm Down Syndrome] |

||

| + | | last =Beck |

||

| − | * [http://www.nelh.nhs.uk/screening/dssp/procedures.htm Down Syndrome testing in UK] |

||

| + | | first =M.N. |

||

| − | * [http://www.laptopical.com/news/laptop-education-19352.html Down Syndrome child learning with laptops] |

||

| + | | year =1999 |

||

| − | * [http://www.nichd.nih.gov/publications/pubs/downsyndrome/down.htm Genetics of Down Syndrome] |

||

| + | | title =Expecting Adam |

||

| − | * [http://www.ygyh.org/ds/whatisit.htm Your Genes/Your Health information on Down syndrome] |

||

| + | | publisher =Berkley Books |

||

| − | * [http://www.ds-health.com/ Down syndrome: Health Issues. Medical Essays and Information] |

||

| + | | location =New York |

||

| − | [[Category:Congenital genetic disorders]] |

||

| + | }} |

||

| + | * {{cite book |

||

| + | | last =Buckley |

||

| + | | first =S. |

||

| + | | year =2000 |

||

| + | | title =Living with Down Syndrome |

||

| + | | publisher =The Down Syndrome Educational Trust |

||

| + | | location =Portsmouth, UK |

||

| + | | url =http://www.down-syndrome.info/library/dsii/01/01/ |

||

| + | }} |

||

| + | * {{cite book |

||

| + | | last =Down Syndrome Research Foundation |

||

| + | | year =2005 |

||

| + | | title =Bright Beginnings: A Guide for New Parents |

||

| + | | publisher =Down Syndrome Research Foundation |

||

| + | | location =Buckinghamshire, UK |

||

| + | | url =http://www.dsrf.co.uk/Reading_material/Bright_beginnings.htm |

||

| + | }} |

||

| + | * Hassold, T.J., D. Patterson, eds. (1999). ''Down Syndrome: A Promising Future, Together''. New York: Wiley Liss. |

||

| + | * {{cite book |

||

| + | | last =Kingsley |

||

| + | | first =J. |

||

| + | | coauthors =M. Levitz |

||

| + | | year =1994 |

||

| + | | title =Count Us In: Growing up with Down Syndrome |

||

| + | | publisher =Harcourt Brace |

||

| + | | location =San Diego |

||

| + | }} |

||

| + | * Pueschel, S.M., M. Sustrova, eds. (1997). ''Adolescents with Down Syndrome: Toward a More Fulfilling Life''. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes. |

||

| + | * {{cite book |

||

| + | | last =Selikowitz |

||

| + | | first =M. |

||

| + | | edition =2nd edition |

||

| + | | year =1997 |

||

| + | | title =Down Syndrome: The Facts |

||

| + | | publisher =Oxford University Press |

||

| + | | location =Oxford, UK |

||

| + | }} |

||

| + | * {{cite book |

||

| + | | last =Van Dyke |

||

| + | | first =D.C. |

||

| + | | coauthors =P.J. Mattheis, S. Schoon Eberly, J. Williams |

||

| + | | year =1995 |

||

| + | | title =Medical and Surgical Care for Children with Down Syndrome |

||

| + | | publisher =Woodbine House |

||

| + | | location =Bethesda, MD |

||

| + | }} |

||

| + | * {{cite book |

||

| + | | last =Zuckoff |

||

| + | | first =M. |

||

| + | | year =2002 |

||

| + | | title =Choosing Naia: A Family's Journey |

||

| + | | publisher =Beacon Press |

||

| + | | location =New York |

||

| + | }} |

||

| + | |||

| + | ==External links== |

||

| + | {{commonscat|Down syndrome}} |

||

| + | For comprehensive lists of Down syndrome links see |

||

| + | *[http://www.downsyndrome.com/ Directory of Down Syndrome Internet Sites (US based, but contains international links)] |

||

| + | *[http://www.43green.freeserve.co.uk/uk_downs_syndrome/index.html UK resources for Down's syndrome] |

||

| + | |||

| + | ===Societies and associations=== |

||

| + | <!-- This list is not for local support organizations, there are simply too many. Contact the lists in the previous subheading to make sure you are listed there, it is more appropriate. --> |

||

| + | *[http://www.down-syndrome-int.org Down Syndrome International] |

||

| + | *[http://www.downsed.org The Down Syndrome Educational Trust] |

||

| + | *[http://www.dsrtf.org Down Syndrome Research and Treatment Foundation] |

||

| + | '''By country''' |

||

| + | *[http://www.cdss.ca Canadian Down Syndrome Society (Canada)] |

||

| + | *[http://www.dsrf.org/ Down Syndrome Research Foundation (Canada)] |

||

| + | *[http://www.dsscotland.org.uk/ Down's Syndrome Scotland (Scotland)] |

||

| + | *[http://www.dsa-uk.com/ Down's Syndrome Association UK (Not including Scotland)] |

||

| + | *[http://www.dsrf.co.uk/ Down's Syndrome Research Foundation (UK)] |

||

| + | *[http://www.ndss.org/ National Down Syndrome Society (USA)] |

||

| + | *[http://www.ndsccenter.org/ National Down Syndrome Congress (USA)] |

||

| + | *[http://www.imdsa.com International Mosaic Down Syndrome Association (USA)] |

||

| + | *[http://www.dhg.org.uk Down's Heart Group (heart conditions related to Down's Syndrome)] |

||

| + | *[http://www.downsyndrome-singapore.org/ Down Syndrome Association (Singapore)] |

||

| + | '''Health & Targeted Nutritional Intervention''' |