(→Papers) |

|||

| (12 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{SocialPsy}} |

{{SocialPsy}} |

||

| + | {{Groups}} |

||

| − | '''Conformity''' is the degree to which members of a [[group (sociology)|group]] will change their behavior, views and [[attitude (psychology)|attitude]]s to fit the views of the group. |

||

| + | '''Conformity''' is a process by which people's beliefs or behaviors are influenced by others within a group. People can be influenced via subtle, even [[unconscious mind|unconscious]] processes, or by direct and overt [[peer pressure]]. Conformity can have either good or bad effects on people, from driving safely on the correct side of the road, to harmful drug or alcohol abuse |

||

| ⚫ | Conformity is a [[group dynamics|group]] behavior. Numerous factors, such as group size, [[unanimity]], [[cohesion]], [[status]], prior [[commitment]] and [[public opinion]] all help to determine the level of conformity an individual will reflect towards his or her group. Conformity influences the formation and maintenance of [[social norm]]s. |

||

| − | The group can influence members via [[unconscious mind|unconscious]] processes or via overt [[peer pressure]]s on individuals. |

||

| − | |||

| ⚫ | |||

== Famous experiments in conformity == |

== Famous experiments in conformity == |

||

| Line 12: | Line 11: | ||

* the [[Milgram experiment]] of [[Stanley Milgram]], which set out to measure the willingness of a participant to obey instructions from [[authority]], even when the instructions (in this case, to '[[torture]]' others by means of electric shocks) conflicted with the participant's personal conscience. |

* the [[Milgram experiment]] of [[Stanley Milgram]], which set out to measure the willingness of a participant to obey instructions from [[authority]], even when the instructions (in this case, to '[[torture]]' others by means of electric shocks) conflicted with the participant's personal conscience. |

||

| − | == |

+ | == Varieties == |

| ⚫ | |||

| + | #''[[Compliance (physiology)|Compliance]]'' is public conformity, while keeping one's own beliefs private. |

||

| + | #''[[Identification]]'' is conforming to someone who is liked and respected, such as a celebrity or a favorite uncle. |

||

| + | #''[[Internalization]]'' is acceptance of the belief or behavior and conforming both publicly and privately. |

||

| + | Although Kelman's distinction has been very influential, research in [[Social psychology (psychology)|social psychology]] has focused primarily on two main varieties of conformity. These are ''informational'' conformity, or informational social influence, and ''normative'' conformity, otherwise known as normative social influence (Aronson, Wilson, & Akert, 2005). Using Kelman's terminology, these correspond to internalization and compliance, or so it is said. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| − | * ''[[compliance]]'' - conforming only publicly, but keeping one's own views in private |

||

| − | * ''[[identification]]'' - conforming while a group member, publicly and privately, but not after leaving the group |

||

| − | * ''[[internalization]]'' - comforming publicly and privately, during and after group membership |

||

| + | === Informational influence === |

||

| − | Sociologists believe that |

||

| + | Informational social influence occurs when one turns to the members of one's group to obtain accurate information. A person is most likely to use informational social influence in three situations: When a situation is [[ambiguous]], people become uncertain about what to do. They are more likely to depend on others for the answer. During a [[crisis]] immediate action is necessary, in spite of panic. Looking to other people can help ease fears, but unfortunately they are not always right. The more knowledgeable a person is, the more valuable they are as a resource. Thus people often turn to [[expert]]s for help. But once again people must be careful, as experts can make mistakes too. Informational social influence often results in ''internalization'' or ''private acceptance'', where a person genuinely believes that the information is right. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | Informational social influence was first documented in [[Muzafer Sherif]]'s (1936) autokinetic experiment. He was interested in how many people change their opinions to bring them in line with the opinion of a group. Participants were placed in a dark room and asked to stare at a small dot of light 15 feet away. They were then asked to estimate the amount it moved. The trick was there was no movement, it was caused by a visual illusion known as the [[autokinetic effect]]. Every person perceived different amounts of movement. Over time, the same estimate was agreed on and others conformed to it. Sherif suggested that this was a simulation for how [[social norm]]s develop in a society, providing a common frame of reference for people. |

||

| − | Another distinction can be made between |

||

| − | * informational conformity (or informational social influence) - occurs when one turns to the members of his group to obtain information on an ambiguous situation (e.g. solving a difficult math problem, deciding where to go to escape a fire) |

||

| − | * normative conformity (or normative social influence)- occurs when one conforms to be liked or accepted by the members of the group |

||

| + | Subsequent experiments were based on more realistic situations. In an eyewitness identification task, participants were shown a suspect individually and then in a lineup of other suspects. They were given one second to identify him, making it a difficult task. One group was told that their input was very important and would be used by the legal community. To the other it was simply a trial. Being more motivated to get the right answer increased the tendency to conform. Those who wanted to be most accurate conformed 51% of the time as opposed to 35% in the other group. This only occurred, however, if the task was very difficult. If the task was made to be quite easy, those who most wanted to be accurate conformed less of the time (16%) than those who didn't feel their answers were important (33%). (Baron, Vandello, & Brunsman, 1996). |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| − | |||

| − | *[[groupthink]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

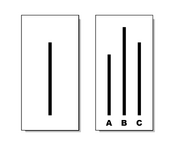

| + | [[Image:Asch experiment.png|thumb|left|Which line matches the first line, A, B, or C? In the [[Asch conformity experiments]], people frequently followed the majority judgment, even when the majority was wrong.]] |

||

| + | |||

| + | === Normative influence === |

||

| + | Normative social influence occurs when one conforms to be liked or accepted by the members of the group. [[Solomon E. Asch]] (1955) was the first psychologist to study this phenomenon in the laboratory. He conducted a modification of Sherif’s study, assuming that when the situation was very clear, conformity would be drastically reduced. He exposed people in a group to a series of lines, and the participants were asked to match one line with a standard line. All participants except one were secretly told to give the wrong answer in 12 of the 18 trials. The results showed a surprisingly high degree of conformity. 76% of the participants conformed on at least one trial. On average people conformed one third of the time. |

||

| + | |||

| + | Normative influence is a function of ''social impact theory'' (Latané, 1981), which has three components. The ''number of people'' in the group has a surprising effect. As the number increases, each person has less of an impact. A group's ''strength'' is how important the group is to you. Groups we value generally have more social influence.''Immediacy'' is how close the group is to you in time and space when the influence is taking place. Psychologists have constructed a mathematical model using these three factors and are able to predict the amount of conformity that occurs with some degree of accuracy (Latane & Bourgeois, 2001). Normative social influence usually results in ''public compliance'', doing or saying something without believing in it. |

||

| + | |||

| + | Baron and his colleagues (1996) conducted a second "eyewitness study", this time focusing on normative influence. In this version, the task was made easier. Each participant was given five seconds to look at a slide, instead of just one second. Once again there were both high and low motives to be accurate, but the results were the reverse of the first study. The low motivation group conformed 33% of the time (similar to Asch's findings). The high motivation group conformed less at 16%. These results show that when accuracy is not very important, it is better to get the wrong answer than to risk social disapproval (Baron, Vandello, & Brunsman, 1996). |

||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | === Reasons for conformity=== |

||

| + | |||

| + | Deutsch & Gerard identified the [[Dual Process Model of Conformity]] (1955) - the two psychological needs that lead humans to conform: |

||

| + | |||

| + | 1. Our need to be right (Informational social influence) and; |

||

| + | |||

| + | 2. Our need to be liked (Normative social influence) |

||

| + | |||

| + | ==Methods== |

||

| + | === Yes-set === |

||

| + | One can ask several trivial questions with the expected answer "yes", building trust and [[acceptance]]. Further questions such as "Will you buy this?" or "Could you borrow this for me?" are then more likely to be answered with "Yes". This technique is used by [[sales]]men, and unconsciously, in conversation. It is also present to a certain extent in the [[Socratic method]] of debate. See also [[selling technique]]. |

||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | *[[Choice shift]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | *[[Groupthink]] |

||

| + | *[[Information cascades]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | *[[Nonconformism]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | *[[Social influences]] |

||

| + | *[[Spiral of silence]] |

||

==References & Bibliography== |

==References & Bibliography== |

||

| Line 56: | Line 88: | ||

* [http://changingminds.org/explanations/needs/conformity.htm Changingminds: Conformity] |

* [http://changingminds.org/explanations/needs/conformity.htm Changingminds: Conformity] |

||

| − | |||

| ⚫ | |||

{{psych-stub}} |

{{psych-stub}} |

||

| + | |||

| − | :de:Konformität |

||

| − | :he:קונפורמיות |

||

| − | :hu:Konformitás |

||

| − | :pl:Konformizm |

||

{{enWP|Conformity (psychology)}} |

{{enWP|Conformity (psychology)}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | [[Category:Social influences]] |

||

Latest revision as of 18:19, 29 May 2013

Assessment |

Biopsychology |

Comparative |

Cognitive |

Developmental |

Language |

Individual differences |

Personality |

Philosophy |

Social |

Methods |

Statistics |

Clinical |

Educational |

Industrial |

Professional items |

World psychology |

Social psychology: Altruism · Attribution · Attitudes · Conformity · Discrimination · Groups · Interpersonal relations · Obedience · Prejudice · Norms · Perception · Index · Outline

Conformity is a process by which people's beliefs or behaviors are influenced by others within a group. People can be influenced via subtle, even unconscious processes, or by direct and overt peer pressure. Conformity can have either good or bad effects on people, from driving safely on the correct side of the road, to harmful drug or alcohol abuse

Conformity is a group behavior. Numerous factors, such as group size, unanimity, cohesion, status, prior commitment and public opinion all help to determine the level of conformity an individual will reflect towards his or her group. Conformity influences the formation and maintenance of social norms.

Famous experiments in conformity

- Muzafer Sherif`s light dot experiment, which measured to what extent a participant, when asked to solve a difficult problem, would compare - and adapt - his answer to that of his fellow participants (a kind of conformity called informational social influence);

- the Asch conformity experiments of Solomon Asch, whose development of the peer pressure theory aided greatly in the modern disciplines of psychology;

- the Milgram experiment of Stanley Milgram, which set out to measure the willingness of a participant to obey instructions from authority, even when the instructions (in this case, to 'torture' others by means of electric shocks) conflicted with the participant's personal conscience.

Varieties

Harvard psychologist, Herbert Kelman (1958) identified three major types of social influence.

- Compliance is public conformity, while keeping one's own beliefs private.

- Identification is conforming to someone who is liked and respected, such as a celebrity or a favorite uncle.

- Internalization is acceptance of the belief or behavior and conforming both publicly and privately.

Although Kelman's distinction has been very influential, research in social psychology has focused primarily on two main varieties of conformity. These are informational conformity, or informational social influence, and normative conformity, otherwise known as normative social influence (Aronson, Wilson, & Akert, 2005). Using Kelman's terminology, these correspond to internalization and compliance, or so it is said.

Informational influence

Informational social influence occurs when one turns to the members of one's group to obtain accurate information. A person is most likely to use informational social influence in three situations: When a situation is ambiguous, people become uncertain about what to do. They are more likely to depend on others for the answer. During a crisis immediate action is necessary, in spite of panic. Looking to other people can help ease fears, but unfortunately they are not always right. The more knowledgeable a person is, the more valuable they are as a resource. Thus people often turn to experts for help. But once again people must be careful, as experts can make mistakes too. Informational social influence often results in internalization or private acceptance, where a person genuinely believes that the information is right.

Informational social influence was first documented in Muzafer Sherif's (1936) autokinetic experiment. He was interested in how many people change their opinions to bring them in line with the opinion of a group. Participants were placed in a dark room and asked to stare at a small dot of light 15 feet away. They were then asked to estimate the amount it moved. The trick was there was no movement, it was caused by a visual illusion known as the autokinetic effect. Every person perceived different amounts of movement. Over time, the same estimate was agreed on and others conformed to it. Sherif suggested that this was a simulation for how social norms develop in a society, providing a common frame of reference for people.

Subsequent experiments were based on more realistic situations. In an eyewitness identification task, participants were shown a suspect individually and then in a lineup of other suspects. They were given one second to identify him, making it a difficult task. One group was told that their input was very important and would be used by the legal community. To the other it was simply a trial. Being more motivated to get the right answer increased the tendency to conform. Those who wanted to be most accurate conformed 51% of the time as opposed to 35% in the other group. This only occurred, however, if the task was very difficult. If the task was made to be quite easy, those who most wanted to be accurate conformed less of the time (16%) than those who didn't feel their answers were important (33%). (Baron, Vandello, & Brunsman, 1996).

Which line matches the first line, A, B, or C? In the Asch conformity experiments, people frequently followed the majority judgment, even when the majority was wrong.

Normative influence

Normative social influence occurs when one conforms to be liked or accepted by the members of the group. Solomon E. Asch (1955) was the first psychologist to study this phenomenon in the laboratory. He conducted a modification of Sherif’s study, assuming that when the situation was very clear, conformity would be drastically reduced. He exposed people in a group to a series of lines, and the participants were asked to match one line with a standard line. All participants except one were secretly told to give the wrong answer in 12 of the 18 trials. The results showed a surprisingly high degree of conformity. 76% of the participants conformed on at least one trial. On average people conformed one third of the time.

Normative influence is a function of social impact theory (Latané, 1981), which has three components. The number of people in the group has a surprising effect. As the number increases, each person has less of an impact. A group's strength is how important the group is to you. Groups we value generally have more social influence.Immediacy is how close the group is to you in time and space when the influence is taking place. Psychologists have constructed a mathematical model using these three factors and are able to predict the amount of conformity that occurs with some degree of accuracy (Latane & Bourgeois, 2001). Normative social influence usually results in public compliance, doing or saying something without believing in it.

Baron and his colleagues (1996) conducted a second "eyewitness study", this time focusing on normative influence. In this version, the task was made easier. Each participant was given five seconds to look at a slide, instead of just one second. Once again there were both high and low motives to be accurate, but the results were the reverse of the first study. The low motivation group conformed 33% of the time (similar to Asch's findings). The high motivation group conformed less at 16%. These results show that when accuracy is not very important, it is better to get the wrong answer than to risk social disapproval (Baron, Vandello, & Brunsman, 1996).

Reasons for conformity

Deutsch & Gerard identified the Dual Process Model of Conformity (1955) - the two psychological needs that lead humans to conform:

1. Our need to be right (Informational social influence) and;

2. Our need to be liked (Normative social influence)

Methods

Yes-set

One can ask several trivial questions with the expected answer "yes", building trust and acceptance. Further questions such as "Will you buy this?" or "Could you borrow this for me?" are then more likely to be answered with "Yes". This technique is used by salesmen, and unconsciously, in conversation. It is also present to a certain extent in the Socratic method of debate. See also selling technique.

See also

- Choice shift

- Compliance is conformity that is usually a result of a direct order,

- Groupthink

- Information cascades

- Internalization is conformity that comes from one's belief in his act.

- Nonconformism

- Peer pressure

- Social influences

- Spiral of silence

References & Bibliography

Key texts

Books

Papers

- Allen, V.L. and Levine, J.M. (1968) Social support, dissent and conformity, Sociometry 31: 138-49.

- Allen, V.L. and Levine, 3.M. (1971) Social pressures and personal influence, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 7: 122-4.

- Crutchfield, R.S. (1955) Conformity and character, American Psychologist 10: 191-8.

- Dons, M. and Avermaet, E. van (1981) The conformity effect: a timeless phenomenon? Bulletin of the British Psychological Society 34: 383-5.

- Kelman, H. (1958). Compliance, identification, and internalization: three processes of attitude change. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 2, 31-60.

- Morris, W.N. and Miller, R.S. (1975) The effects of consensus-breaking and consensus-preempting partners on reduction of conformity, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 11:215-23.

- Nicolson, N., Cole, S.G. and Rocklon, T. (1985) Conformity in the Asch situation: a comparison between contemporary British and American university students, British Journal of Social Psychology 24: 91-8.

- Toder, N.L. and Marcia, J.E. (1973) Ego-identity status and response to conformity pressure in college women, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 26: 287-94.

- Weisenthal, D.L., Endler, N.S., Coward, T.R. and Edwards, J. (1976) Reversability of relative competence as a determinant of conformity across different perceptual tasks, Representative Research in Social Psychology 7: 35-43.

Further reading

- Gil-White, F.J. (2005). How conformism creates ethnicity creates conformism (and why this matters to lots of things) The Monist, 88, 189-237. Full text

External links

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia (view authors). |