(New page: {{PhilPsy}} {{Platonism}} The '''Allegory of The Cave''' is an allegory used by the Greek philosopher Plato in ''Republic''. The allegory is told then inter...) |

(-L) |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

{{Platonism}} |

{{Platonism}} |

||

| − | The '''Allegory of The Cave''' is an |

+ | The '''Allegory of The Cave''' is an allegory used by the Greek philosopher [[Plato]] in ''[[Republic (Plato)|Republic]]''. The allegory is told then interpreted by the character Socrates at the beginning of Book 7 (514a–520a). It is related to the [[Plato's metaphor of the sun|metaphor of the sun]] (507b–509c) and the [[analogy of the divided line]] (509d–513e). Allegories are summarized in the viewpoint of dialectic the end of book VII (531d-534e). |

==Plot== |

==Plot== |

||

| − | Imagine |

+ | Imagine prisoners, who have been chained since diapers deep inside a cave: not only are their limbs immobilized by the chains; their heads are chained as well, so that their gaze is fixed on a wall. |

| − | Behind the prisoners is an enormous |

+ | Behind the prisoners is an enormous fire, and between the fire and the prisoners is a raised walkway, along which statues of various animals, plants, and other things are carried by people. The statues cast shadows on the wall, and the prisoners watch these shadows. When one of the statue-carriers speaks, an echo against the wall causes the prisoners to believe that the words come from the shadows. |

The prisoners engage in what appears to us to be a game: naming the shapes as they come by. This, however, is the only reality that they know, even though they are seeing merely shadows of images. They are thus conditioned to judge the quality of one another by their skill in quickly naming the shapes and dislike those who begin to play poorly. |

The prisoners engage in what appears to us to be a game: naming the shapes as they come by. This, however, is the only reality that they know, even though they are seeing merely shadows of images. They are thus conditioned to judge the quality of one another by their skill in quickly naming the shapes and dislike those who begin to play poorly. |

||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

Suppose a prisoner is released and compelled to stand up and turn around. At that moment his eyes will be blinded by the firelight, and the shapes passing will appear less real than their shadows. |

Suppose a prisoner is released and compelled to stand up and turn around. At that moment his eyes will be blinded by the firelight, and the shapes passing will appear less real than their shadows. |

||

| − | Similarly, if he is dragged up out of the cave into the |

+ | Similarly, if he is dragged up out of the cave into the sunlight, his eyes will be so blinded that he will not be able to see anything. |

At first, he will be able to see darker shapes such as shadows and, only later, brighter and brighter objects. |

At first, he will be able to see darker shapes such as shadows and, only later, brighter and brighter objects. |

||

| − | The last object he would be able to see is the |

+ | The last object he would be able to see is the sun, which, in time, he would learn to see as that object which provides the seasons and the courses of the year, presides over all things in the visible region, and is in some way the cause of all these things that he has seen. |

(This part of the allegory, incidentally, closely matches [[Plato's metaphor of the sun]] which occurs near the end of ''The Republic'', Book VI.) |

(This part of the allegory, incidentally, closely matches [[Plato's metaphor of the sun]] which occurs near the end of ''The Republic'', Book VI.) |

||

Revision as of 23:02, 22 April 2007

Assessment |

Biopsychology |

Comparative |

Cognitive |

Developmental |

Language |

Individual differences |

Personality |

Philosophy |

Social |

Methods |

Statistics |

Clinical |

Educational |

Industrial |

Professional items |

World psychology |

Philosophy Index: Aesthetics · Epistemology · Ethics · Logic · Metaphysics · Consciousness · Philosophy of Language · Philosophy of Mind · Philosophy of Science · Social and Political philosophy · Philosophies · Philosophers · List of lists

| Platonism |

| Platonic idealism |

| Platonic realism |

| Middle Platonism |

| Neoplatonism |

| Articles on Neoplatonism |

| Platonic epistemology |

| Socratic method |

| Socratic dialogue |

| Theory of forms |

| Platonic doctrine of recollection |

| Individuals |

| Plato |

| Socrates |

| Discussions of Plato's works |

| Dialogues of Plato |

| Plato's metaphor of the sun |

| Analogy of the divided line |

| Allegory of the cave

|

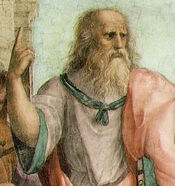

The Allegory of The Cave is an allegory used by the Greek philosopher Plato in Republic. The allegory is told then interpreted by the character Socrates at the beginning of Book 7 (514a–520a). It is related to the metaphor of the sun (507b–509c) and the analogy of the divided line (509d–513e). Allegories are summarized in the viewpoint of dialectic the end of book VII (531d-534e).

Plot

Imagine prisoners, who have been chained since diapers deep inside a cave: not only are their limbs immobilized by the chains; their heads are chained as well, so that their gaze is fixed on a wall.

Behind the prisoners is an enormous fire, and between the fire and the prisoners is a raised walkway, along which statues of various animals, plants, and other things are carried by people. The statues cast shadows on the wall, and the prisoners watch these shadows. When one of the statue-carriers speaks, an echo against the wall causes the prisoners to believe that the words come from the shadows.

The prisoners engage in what appears to us to be a game: naming the shapes as they come by. This, however, is the only reality that they know, even though they are seeing merely shadows of images. They are thus conditioned to judge the quality of one another by their skill in quickly naming the shapes and dislike those who begin to play poorly.

Suppose a prisoner is released and compelled to stand up and turn around. At that moment his eyes will be blinded by the firelight, and the shapes passing will appear less real than their shadows.

Similarly, if he is dragged up out of the cave into the sunlight, his eyes will be so blinded that he will not be able to see anything. At first, he will be able to see darker shapes such as shadows and, only later, brighter and brighter objects.

The last object he would be able to see is the sun, which, in time, he would learn to see as that object which provides the seasons and the courses of the year, presides over all things in the visible region, and is in some way the cause of all these things that he has seen.

(This part of the allegory, incidentally, closely matches Plato's metaphor of the sun which occurs near the end of The Republic, Book VI.)

Once enlightened, so to speak, the freed prisoner would not want to return to the cave to free "his fellow bondsmen," but would be compelled to do so. Another problem lies in the other prisoners not wanting to be freed: descending back into the cave would require that the freed prisoner's eyes adjust again, and for a time, he would be one of the ones identifying shapes on the wall. His eyes would be swamped by the darkness, and would take time to become acclimated. Therefore, he would not be able to identify shapes on the wall as well as the other prisoners, making it seem as if his being taken to the surface completely ruined his eyesight. (The Republic bk. VII, 516b-c; trans. Paul Shorey).

Interpretation

Socrates himself interprets the allegory (beginning at 517b): "This image then [the allegory of the cave] we must apply as a whole to all that has been said"—i.e. the preceding analogy of the divided line and metaphor of the sun.

It has been up to scholarly debate in 20th century how exactly these three sequential comparisons can be coherently bound together. Main problems arise from allegory of cave having three cognitive stages and divided line having four of them where the first division (shadows, reflections) seems not to be needed to apply to cave and is hard to be interpreted ontologically, i.e. in the manner of cave at all. Metaphor of the sun seems to be alluding that from seeing things in light of sun we can raise to seeing ideas in the light of the Good while in cave it is not evident that it can not be done without considerably violent helping and forcing prisoners to look at light.

Plato's own remarks on the allegory

In particular, Plato likens "the region revealed through sight"—the ordinary objects we see around us—"to the habitation of the prison, and the light of the fire in it to the power of the sun. And if you assume the ascent and the contemplation of the things above is the soul's ascension to the intelligible region, you will not miss my surmise...[M]y dream as it appears to me is that in the region of the known the last thing to be seen and hardly seen is the idea of good, and that when seen it must needs point us to the conclusion that this is indeed the cause for all things of all that is right and beautiful, giving birth in the visible world to light, and the author of light and itself in the intelligible world being the authentic source of truth and reason..." (517b-c). After "returning from divine contemplations to the petty miseries of men", one is apt to cut "a sorry figure" if, "while still blinking through the gloom, and before he has become sufficiently accustomed to the environing darkness, he is compelled in courtrooms or elsewhere to contend about the shadows of justice or the images that cast the shadows and to wrangle in debate about the notions of these things in the minds of those who have never seen justice itself?" (517d-e)

Interpretation of the idealist tradition

Another interpretation is that of the Idealists. As in the philosophy of George Berkeley, it is understood that we do not directly and immediately know real external objects; we only directly know the effect that reality has on our minds. In other words, we immediately know only shadowy inner mental images of real external objects. The real external objects themselves cannot be immediately and directly known. In the Appendix to his main work, Schopenhauer expressed it as follows:

This world that appears to the senses has no true being, but only a ceaseless becoming; it is, and it also is not; and its comprehension is not so much a knowledge as an illusion. This is what he expresses in a myth at the beginning of the seventh book of the Republic, the most important passage in all his works … . He says that men, firmly chained in a dark cave, see neither the genuine original light nor actual things, but only the inadequate light of the fire in the cave, and the shadows of actual things passing by the fire behind their backs. Yet they imagine that the shadows are the reality, and that determining the succession of these shadows is true wisdom.

— The World as Will and Representation, Vol. I, Appendix

Different grounds for interpretation

One can also choose whether the meaning of allegory is epistemological or ontological, i.e. are the shadows to be correlated with things in our world of sight, the things in cave with mathematical entities, and things outside cave with ideas or should we just concentrate on the cognitive stages. It has been claimed that purely epistemological view is foreign to greek tradition and especially Plato, that is the reading should bring ontological statements within.

Besides cognitive interpretations the allegory has also clear political implications, for example the fourth stage of returning to cave to help fellow-prisoners. Also the play of shadows can be interpreted as political juggling over citizens heads and this seems to be natural because of the whole context of Republic. Since the highest knowledge in allegory is The Good then the interpretation should bring together at least ethical allusions about attaining virtues.

However, Plato himself introduces the allegory of cave letting Socrates say that it is about education (paideia) and miseducatedness (apaideusia).

Movements between stages

Since allegory is by Socrates' words about education, it should be interpreted from the viewpoint of conditions for taking steps toward higher stages, i.e. conditions for education.

There are four steps described: (1) prisoners who think that shadows are reality; (2) prisoners who are freed and forced look at the things that are used to cast shadows on the wall and do not recognize these as sources for shadows; (3) prisoners who are freed and dragged along to the outside of cave; (4) free men returning to the cave to former fellow-prisoners.

Step (3) has also four sub-steps of looking at (a) shadows, (b) things that cast shadows, (c) heavenly bodies, (d) sun as the source and guarantee of all the things outside cave.

Substeps beneath step (3) cohere notably with analogy of the divided line. Confrontation between cave and outside can be explained by metaphor of sun, but there is one major difference: in the cave one cannot deduce from whatever position that burning artificial light and things that are carried are the source for shadows. Metaphor of the sun argues but that this kind of deduction is possible.

All the steps have their proper interpretation from ontological, epistemological and ethical point of view.

Cultural references

John Lennon makes reference to the allegory in his song, "Watching the Wheels." In this song, Lennon declares his willful decline from the limelight world of The Beatles:

People say I'm lazy, dreaming my life away,

Well, they give me all kinds of advice designed to enlighten me

When I tell 'em that I'm doing fine, watching shadows on the wall

"Don't you miss the big time, boy? You're no longer on the ball"

A reference to Plato's Cave can also be found recently in a song written by Jack Johnson (musician) on his album titled Brushfire Fairytales. The song containing the reference is titled "Inaudible Melodies" and the verse that this reference is contained in as quoted below:

"Well Plato's cave is full of freaks, demanding refunds for the things they've seen. I wish they could believe in all the things that never made the screen"

This verse not only references the title of the allegory, but certain details about the allegory as well.

There is a They Might Be Giants song, on the album "John Henry", entitled "No One Knows My Plan", which mentions "in the allegory of the people in the cave, by the greek guy".

See also

- Analogy of the divided line

- Maya (illusion)

- Simulated Reality

- The Cave (novel)

External links

- Video interpretation of the Cave by students at American University on YouTube

- Plato: The Allegory of the Cave, from The Republic at Washington State University

- Plato: The Republic at Project Gutenberg

- Plato: The Allegory of the Cave, from The Republic at University of Washington - Faculty

- The Allegory of the Cave: From Book VII of the Republic Free mp3 downloads Narrated by Michael Scott of ThoughtAudio.com

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia (view authors). |